Reflections on a Pauline Pilgrimage to Turkey [15]

“Do not quench the Spirit. Do not despise the words of prophets, but test everything; hold fast to what is good, abstain from every form of evil.” [1 Thessalonians 5:19-22]

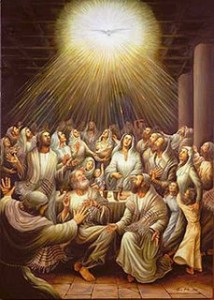

[1] Cathedral of the Holy Spirit, Istanbul. [2] Interior of the Cathedral. [3] The Altarpiece depicting the Pentecost . Photo © Teresa Sim.

It was most fitting that the last Mass of our tour was celebrated at the Cathedral of the Holy Spirit [a.k.a. the St. Esprit Cathedral] in Istanbul. We began with the Spirit, and it was most heartening to wrap up the trip on the Spirit, before heading home.

This is the second largest Catholic church in the city after the St. Anthony of Padua Cathedral. A Baroque style church showing a revival of the early Christian basilica type, it was built in 1846 by Swiss-Italian architect Giuseppe Fossati and directed by his colleague Julien Hillereau. The site where the cathedral stands was chosen because the Vatican had decided to establish its “unofficial” office in Istanbul on the same street. This office today serves in an official capacity as Turkey and the Vatican agreed to establish mutual diplomatic representative offices in 1960.

St. Esprit has been a destination of several papal visits to Turkey, including those of Pope Paul VI, Pope John Paul II, and Pope Benedict XVI. Of special interest to us is the fact that Pope John XXIII, known for his inspiration under the Holy Spirit to call for the Second Vatican Council, as Archbishop Angelo Roncalli was papal representative in Turkey from 1935 to 1944. He won many friends by learning Turkish and using it in the Masses he preached at this cathedral. During Pope Benedict XVI’s trip to Turkey in 2006, he repeatedly referred to Roncalli, especially his saying “I love the Turks.”

The Altarpiece

The altarpiece in this cathedral is appropriately a scene taken from the descent of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost. According to The Institute for Sacred Architecture, an altarpiece is a framed artistic representation of a sacred subject or combination of subjects that “came into existence as a result of particular customs of liturgical and devotional practice; its formal development was shaped by vernacular traditions in Christian sacred art.”

Mention Pentecost and at once the story from Acts 2:1-13 flashes across our minds: we see the disciples gathered in the upper room, we hear a sound like the rush of violent wind filling the house, we behold divided tongues, as of fire, appearing and resting on each disciple, and we picture drunken chaos in which people are speaking, hearing, and understanding strange new languages.

Right before Pentecost, the disciples were afraid, in darkness with regards to the truth, and locked behind closed doors. “Darkness” and “locked doors” are good descriptions of a great deal of our own human conditions. To overcome that darkness and to open the doors to new life, what we need is the Spirit of Truth, the Advocate who will stand on our side and not leave us orphaned, to teach us everything and remind us of all Jesus said (John 14:26), and to guide us into all truth (16:13) – truth about God and truth about ourselves. In a word, what we need is pentecosting by Christ. Invite him in, and he will stand in the midst of our locked houses, breathe into us and send forth the fire, the wind, and the tongues of Pentecost. His Holy Spirit will illumine our hearts, push back the darkness, unlock our closed doors and lead us to proclaim the great deeds of God.

What caught our attention in this altarpiece is the fact that this painting shows not just the Twelve Apostles, as is common amongst certain other “vernacular traditions”. Rather, included amongst those anointed by the outpouring Holy Spirit are Mother Mary, certainly the Apostles, but a big group as well of the first disciples of Jesus who, according to St Luke, numbered some one hundred and twenty (Acts 1:15; 2:1). In this regard, if a painting is a window to the “traditions”, “theologies”, or “biblical interpretations” or what have you behind it, then different paintings are windows to a variety of these realities, which could be either exclusive or inclusive in scope and orientation, that seek to “educate” the viewers’ minds. Take a look at some variations given below and see if they help grow an awareness of the different interpretations and agendas they represent.

[1] Only the Twelve.. [2] Eleven plus St Paul [top right, opposite St Peter].[3] Mary and the Twelve.

[4] Mary with the Twelve and a few women.. [5] The entire Body of Disciples, children included.

[4] Mary with the Twelve and a few women.. [5] The entire Body of Disciples, children included.

Creation Praises the Spirit and Moans

The entire Bible, in both its Old and New Testaments, resounds with praises for the work of the Holy Spirit. In Genesis, the Holy Spirit is poised over the surface of chaos, waiting for the very Word of God, ever ready to convert disorder into order and beauty [Genesis 1:2]. The Holy Spirit is the Creator’s breath of life, breathed into our humanity, giving life to our relationships with God and each other [Genesis 2:7]. Without the Spirit, our life is diminished, no more than dry bones abandoned and forgotten in the wilderness [Ezekiel 37]. The Spirit teaches that our God is God of Mission, loving the world so much that he sent his only Son [John 3:16], born of a woman [Galatians 4:4]. It is the Spirit that effectuates the Incarnation [Luke 1:35]. At baptism, the Spirit is given to us as strength in the face of temptations, and drives us to work for the Kingdom of God [Mark 1:9-15]. This is the Spirit that changes hearts of stone into hearts of flesh, dropping scales from our eyes so we may see the truth of our persecution of others [Acts 9:18] and bringing us to a life of humility in the love of God [1 Corinthians 13]. The Acts of the Apostles describes the outpouring of the Holy Spirit as the birth of the Church, breaking down barriers and converting crowds of different races and different tongues into a single community of faith and understanding and of true communal living [Acts 2]. The Spirit is the abiding principle cementing the vast and immense diversity within the Church into one Body [1 Corinthians 12]. The Spirit is the deeper reality persuading members to stay as “Church the People of God”, despite human systems and structures that seek to govern but, more often, stifle and control for a small-group interest, instead of empower and promote for the larger common good. Where sins splinter and scatter, the Spirit works to reconcile and unite. A broken world longs for communion, in spirit and in truth, to understand and to be understood, to comfort and to be comforted, to set free and to be liberated.

God created a paradise and sin ruined it. As St Paul talks about “the whole of creation” in a state of sin groaning for redemption and hoping to be set free [Romans 8:22-23], our thoughts go to the People of God finding themselves caught in sometimes dysfunctional and often spirit-stifling systems and structures, groaning and hoping for the intervention of the Spirit. Wherever in the world Christian congregations are starving, it would not be for doctrinal orthodoxy or liturgical correctness, but for life in communion with the triune God through the life-giving Spirit. What these churches need – what we all need – is the subversive presence of the Spirit who defeats and breaks the chains of the strong enslaving the weak. It is one thing to use the Parable of the Sower [Matthew 13:1-23] to remind the people to prepare the soil well so that the seeds will fall on good ground and produce multifold harvest. It is quite something else to be reminded by a member of the pew thus: “Look around. Do you not see us eager and educated laity in the congregation? Our soil is rich. We have for way too long been avoiding the real issue. The problem is not the soil, which is well tilled and eager to receive. The problem is with the seeds the sower at the pulpit is distributing. These seeds are of poor quality, often confused for the good seeds in the Parable.” So the problems actually redound to the real life sower himself, his moral life, his example. This kind of incisive response from the pews highlights the truth of which Pope Paul VI has famously observed:

“Modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if he does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses.”

The whole people of God are yearning to be encountered by the God who gives up the idea of God and kenotically empties himself of titles and status [Philippians 2:5-11] to become incarnate in the demands and struggles of daily life. We long for this God. Our baptism is the beginning of our mission to proclaim before the world this God who by the power of the Spirit animates Christian worship in the name of Jesus Christ.

And so we recall the deeds of Jesus as he journeyed towards Jerusalem and towards the Holy Week. In order that all peoples might have equal access to God and to worship in spirit and in truth, Jesus symbolically cleansed the temple and pointed to himself as the Lamb, to be sacrificed once and for all, to yield the universal locus for faith and worship. The torn veil in the Temple, contemporaneous with Jesus’ ultimate sacrifice on the cross, opened once and for all the free access for all and sundry to God’s seat of mercy hitherto opened exclusively to the clerical tribe. In Jesus Christ, God put an end to the artificial separation of the class of priests, who alone had access to the private recess of God, from the rest of humanity whom their system disqualified. As a lay person from Nazareth, Jesus risked his life challenging the conduct of the official religious system and structures. Structures and system came under the exclusive purview of the religious elite and powerful in charge of the temple – the clerics of the day – whose legalistic interpretations of the Law kept the people in slavery rather than set them free. But Jesus the lay person from Nazareth overturned their tables of interests and privileges – all contrary to God because they worked to exclude rather than to include, to dominate rather than to love. His first disciples, living under the system of the day, were at risk of being unconsciously influenced by it, to fall prey to the lure of that empty elitism instead of doing real work of community-building for God. So Jesus promised to send the Holy Spirit, that they might learn to minister like him, in contrast to the system prevailing at the time.

The Spirit of Jesus is always working towards deeper communion. The Spirit is the enabler, our living communion with Christ, for no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’, St Paul declares, unless he or she is under the influence of the Holy Spirit [1 Cor 12:3]. As former arch-persecutor of the Church, St Paul realized the debt he owed the Holy Spirit for the grace working in his heart that enabled him to say, and mean, that Jesus is Lord of our lives. Everywhere he looked, Paul the Apostle to the Gentiles and planter of churches of God in Asia Minor and around the Mediterranean region, saw that the communities that responded to the Gospel were alive in the Spirit. In First Corinthians, he insists that there is no lack of the gifts of the Holy Spirit, but the only question is how these gifts are harnessed and exercised for the common good. Unpacking Pauline ecclesiology during his lecture tour of Malaysia-Singapore-Brunei a few years ago, renowned New Testament Professor Raymond Collins calls it a blasphemy to fail to recognize “the variety of gifts” in the community because they come from the same Spirit, or “the variety of services to be done” because they come from the same Lord. It is equally blasphemous, he says, to insist on one’s gift or position or ministry as being superior to others in gross neglect of the truth that there are many-and-yet-equal parts in one body. Only in the Spirit is there humility before God. And only in the Spirit can one reach beyond labels and titles which by their very nature distinguish and divide, rather than embrace and unite. The Church exists for mission, not for its own sake. To have something to say to the secular world, the Church of Christ must be distinguished, less by the secular world’s zealously-guarded systems of honours and titles, but by Christ’s own self-emptying Spirit to ensure true communal living and in genuine, sacrificial service of the Kingdom of God.

Finally, rounding up our journey at this Holy Spirit Cathedral reminds us to stay rooted in the uniting and life-giving force in the universe called the Holy Spirit of God. In contemplation, we are brought to the truth that the world we see around us of broken people and institutions is only a small portion of what is real. While Christians are duty-bound to work for social transformation, in society as well as in the church, we must stay rooted in the transforming work that the Spirit is constantly doing in us and in the world. This realization provides the fresh impetus that we so badly need, in the face of “failure” and “decline” – and other words by which we so easily associate with the Christian mission in Turkey as in our local faith communities. Recalling the report in Acts of the sound “like the rush of a violent wind” and tongues “as of fire” resting above each disciple’s head, our confidence is restored, our faith renewed. The Holy Spirit is in and with the Church, despite the degradation within and without. In fact, that the Church as the People of God continues to live and exist despite her monumental sins is, from our perspective, evidence enough of the presence of the Holy Spirit. For that, we are truly grateful to God.

St Paul yielded to this same Spirit, and his life portrays a faithful imitation of his Lord.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, March 2012. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.