Reflections on a Pauline Pilgrimage to Turkey [14]

“”For in Him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or principalities or authorities – all things were created through Him and for Him.” [Colossians 1:16]

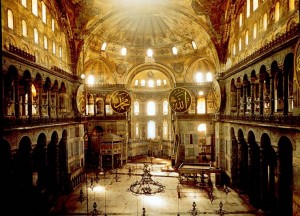

Hagia Sophia is simply magnificent and a must-see for Christian pilgrims who land in Istanbul.

Scriptures define faith as the “assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen” [Hebrews 11:1]. Aesthetics, on the other hand, pertains to a sense of the beautiful in its critical reflection on art, culture and nature. If Christian meditation is thought, emotion, and imagination that leads to prayer – to conversation with God – then one way to approach it is not a book, but a work of art. As Ben Okri realizes, “the highest things are beyond words. That is probably why all art aspires to the condition of wordlessness. … Art wants to move into silence, into the emotional and spiritual conditions of the world.” With its marvelous architecture and beautiful frescoes, Hagia Sophia combines faith and aesthetics to offer every pilgrim an incredible celebration of beauty.

Better known by its Greek name, Hagia Sophia is The Church of the Holy Wisdom (Saint Sophia in English, Sancta Sophia in Latin, and Ayasofya in Turkish). It is a former Byzantine church to which four minarets were added outside and Islamic calligraphy painted inside after the Ottomans captured Constantinople in 1453. Now a museum, Hagia Sophia is universally acknowledged as one of the great buildings of the world.

[L] Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. [M] [M] Hagia Sophia dome paintings. [R] The interior of Hagia Sophia.

Two names preceded Istanbul. First, Byzantium was a settlement in the early days of Greek colonial expansion in the 7th century BC. Next, when the Roman emperor Constantine I founded the city of Constantinople in 330 AD, he did so on the site of the existing city. Sitting on an excellent and spacious harbor, the city offered an ideal link by land route from Europe to Asia and by sea from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Constantine, who had united the empire through the battlefield, set his vision on major governmental reforms as well as sponsoring the consolidation of the Christian church. He found Rome unsatisfactory as the empire’s capital city. Filled as it was with disaffected politicians, it was also too far from the frontiers. Even though it was unthinkable to suggest that a capital for over a thousand years should be moved to a different location, Constantine nevertheless went ahead and identified the site of Byzantium as the right place. There, he visualized, the emperor would sit, defend himself readily, have easy access to the Danube or the Euphrates frontiers, his court supplied from the rich gardens and sophisticated workshops of Asia Minor, and his treasuries filled by the wealthiest and most hardworking provinces of the Empire.

Of Constantinople, the Catholic Encyclopedia wrote: “The most beautiful statues of antiquity were gathered from various parts of the empire to adorn its public places. In general the other cities of the Roman world were stripped to embellish the ‘New Rome’, destined henceforth to surpass them all in greatness and magnificence.” When, therefore, Constantine built the original Hagia Sophia on this site in the fourth century, we can imagine his vision of grandeur for the church. Unfortunately, nothing remains of the original Hagia Sophia. Destroyed in riots, Hagia Sophia was rebuilt in her present form between 532 and 537 under the personal supervision of Emperor Justinian I who, after its completion, had made two euphoric statements: Νενίκηκά σε Σολομών (“Solomon, I have outdone thee!”), and calling it the “Greatest Church in Christendom”. It is certainly one of the greatest surviving examples of Byzantine architecture, rich with mosaics and marble pillars and coverings.

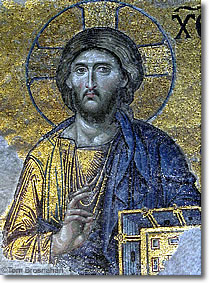

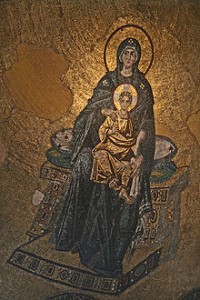

[L] Jesus Christ in the Deesis. [R] [M] Virgin and Child flanked by Justinian I and Constantin.e.

One of the most famous structures in Istanbul, Hagia Sophia’s commanding dome beckons from a distance. The Dome of Santa Sophia, built in the 500s in an earthquake zone, is 107ft in diameter and rises to 184 feet (56 metres, about 15 stories) in height. It is quite awesome to stand in the great big space underneath it and marvel at its age, its size, and its Byzantine architectural achievement. The highest and widest masonry dome ever constructed is Brunelleschi’s Dome on the Duomo in Florence, built nearly 1000 years later, with a dome measuring 142 feet in diameter. The ancient Roman Pantheon is also 142 feet, but its spherical section is not nearly as high. St Peter’s Basilica in Rome is 132 feet, and St Paul’s Cathedral in London is 112 feet.

Byzantine architecture was developed in Byzantium between 4th and 15th centuries. It is characterized by domes over square areas, round arches and elaborate arches. The interior of Byzantine churches would of course be decorated by beautiful icons, and those in Hagia Sophia are quite breathtaking in colours and design.

We were particularly mesmerized by the mosaic of Jesus Christ on the first floor.

This mosaic face of Christ in the Deesis trinity (Mary, Jesus and John the Baptist) is probably one of the best known images in the Christian world. His eyes follow you wherever you go on that huge and spacious upper floor.

A word on faith and art

Hagia Sophia had suffered criminal damage to many of its icons during the period of the iconoclasm controversy in the 8th and 9th centuries. Iconoclasm is the deliberate destruction of religious icons and other symbols or monuments, usually for religious or political motives. New icons were created in Hagia Sophia after the end of iconoclasm in 843, hence the oldest surviving icon in that church is from 860s, which is the Virgin and Child in the apse.

On our part, we believe the human person is so structured that we are endowed with multi-dimensional sensitivity. There is in each one of us an innate longing to touch, taste, see, feel and hear divine essence in our lives so that whenever we have visual and audio and other sensational and intuitive experiences of the presence of God, our being echoes in inner joy. We saw this first hand in Belgium. One day we brought a Protestant classmate of ours in theology to a Franciscan church in the city of Leuven. On entering the church and seeing the row of beautiful stained glasses, he spontaneously burst out, albeit very softly – which means giving voice to an echo of inner joy! – “This is so beautiful!” We just watched him and smiled.

Throughout Christian history, the role of visual arts in worship has often been controversial, with debates being waged on both theological and cultural grounds. In this love-hate relationship with the arts, Christians have oscillated between using them for liturgical and educational purposes and dismissing them as merely decorative and even offensive and idolatrous.

However, people who have experienced the beauty of art know the great value of art to faith life. Praising the virtues of art, these people attest to a long list of positive contributions art makes to faith. We shall leave for another occasion a discussion on the biblical arguments in favour of art. For now, we shall just mention a few of the positive elements people attest to and which readily come to mind:

- Art is a way of telling the human story, as we know it through the Judeo-Christian lenses, over and over again to help feed the Church’s corporate memory.

- All good comes from God, so beauty exposes God.

- Art is a medium for encountering God.

- Good art points beyond itself and helps us recognize the human condition. It transforms us and enriches our notions of God and of humanity.

- Visual art in worship can act as a vehicle of proclamation, and has in fact been used by Jesus Himself.

- Images in illustrated children’s Bible are sermons of childhood, convincing us that art is an essential tool for faith formation.

- Religious art is an essential tool for spiritual formation, Rembrandt’s The Return of the Prodigal Son being a classic example.

- Engaging the arts uses a different side of the brain than people normally do in the routine and demands of daily life and thus enhances deeper spiritual growth.

- Art has revelatory power.

Mosaic and Community

“A mosaic consists of thousands of little stones,” Henri Nouwen wrote in Bread for the Journey. “Some are blue, some are green, some are yellow, some are gold. When we bring our faces close to the mosaic, we can admire the beauty of each stone. But as we step back from it, we can see that all these little stones reveal to us a beautiful picture, telling a story that none of these stones can tell by itself. That is what our life in community is about. Each of us is like a little stone, but together we reveal the face of God to the world. Nobody can say: “I make God visible.” But others who see us together can say: ‘They make God visible.” Community is where humility and glory touch.’”

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, February, 2012. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.