And whenever you fast, do not look dismal, like the hypocrites, for they disfigure their faces so as to show others that they are fasting. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward. But when you fast, put oil on your head and wash your face, so that your fasting may be seen not by others but by your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you. [Matthew 6:16-18, NRSV]

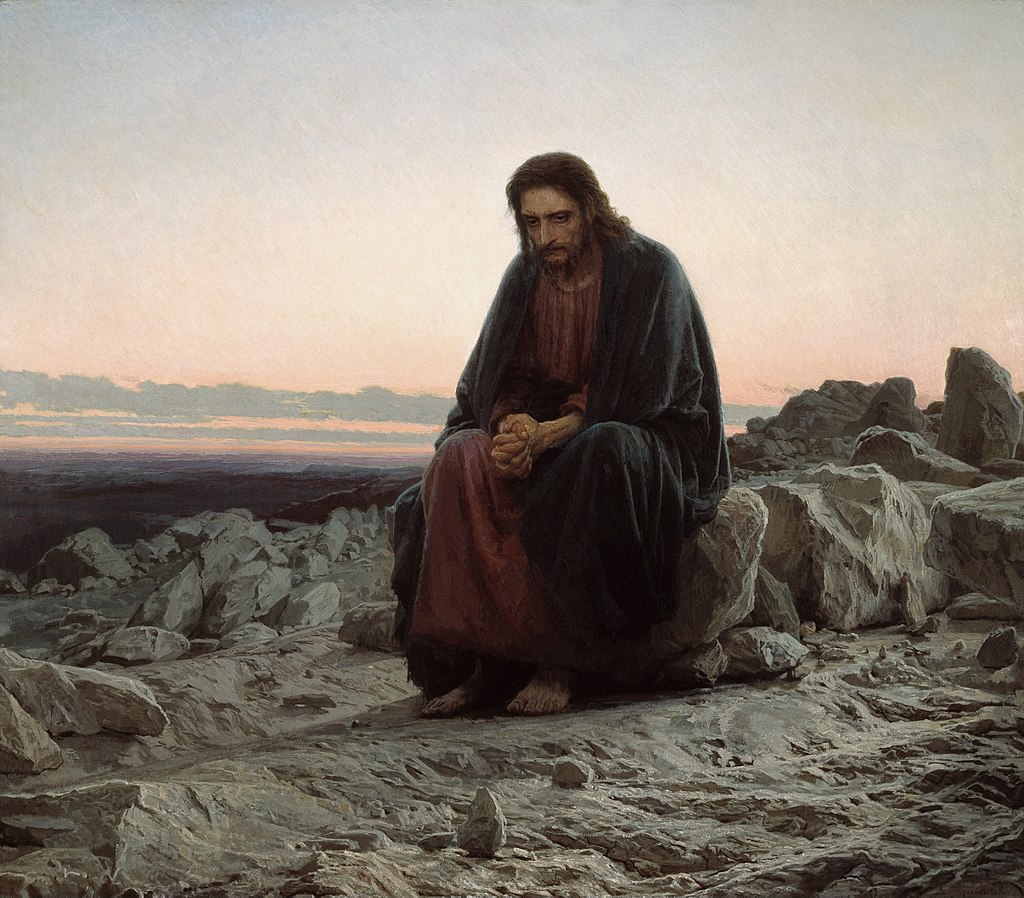

Ivan Kramskoy, Christ in the Wilderness, 1872

Ivan Kramskoy, Christ in the Wilderness, 1872

Stories from the Old Testament

When he heard the reluctant prophet Jonah’s prophecy of God’s wrath over the people of Nineveh’s wickedness, the king of Nineveh at once embarked on a regime of fasting and penance that was as stunning as it was scary to even imagine. He rose from the throne, took off his robe, put on sackcloth and sat in ashes, and proclaimed a total fast on food and water across the entire kingdom, humans and beasts alike (Jonah 3:1-10). What an incredible posture of penance! That story teaches that Scripture is at its best when the Word of God tears not our garments but our hearts and impels us to mourn:

- “Yet even now,” says the Lord, “return to me with all your heart, with fasting, with weeping, and with mourning; and rend your hearts and not your garments” [Joel 2:12-13].

Prayer and fasting was often done in times of distress or trouble. David fasted when he learned that Saul and son Jonathan had been killed (2 Samuel 1:12). He kept a strict fast and slept on bare ground for seven days while Bethsheba’s son was gravely ill (2 Samuel 12:16-19). Nehemiah prayed and fasted for days upon learning that Jerusalem was still in ruins (Nehemiah 1:4). Darius, the king of Persia, fasted all night after he was forced to put Daniel in the den of lions (Daniel 6:18). Needing army protection and confused as to what to do, Ezra the priest fasted and prayed for an answer (Ezra 8:23). King Jehoshaphat called for a fast in all Israel when they were about to be attacked by the Moabites and Ammonites (2 Chronicles 20:3).

Samuel led God’s people in a fast to celebrate the return of the Ark of the Covenant from its captivity by the Philistines, and to pray that Israel might be delivered from idolatry that allowed the Ark to be captured in the first place. “So they gathered at Mizpah, and drew water, and poured it out before the Lord. And they fasted that day, and said there, ‘We have sinned against the Lord’” (1 Samuel 7:6).

Moses fasted during the 40 days and 40 nights he was on Mount Sinai receiving the law from God (Exodus 34:28).

Elijah deliberately went without food when he fled from Queen Jezebel’s threat to kill him. After this self-imposed deprivation, God sent an angel to minister to Elijah in the wilderness. “But he himself went a day’s journey into the wilderness…. And he arose, and ate and drank, and went in the strength of that food forty days and nights to Horeb the mount of God” (1 Kings 19:4-8).

Yet the Old Testament law does not specifically require prayer and fasting, except for one occasion, which was the Day of Atonement. This custom became known as “the day of fasting” (Jeremiah 36:6) or “the Fast” (Acts 27:9).

Stories from the New Testament

For Christians, the best starting point for insights into prayer and fasting is the Lord Jesus’ forty days of fasting and prayer in the wilderness before beginning His public ministry. The story is told in Matthew 4, Mark 1 and Luke 4. The setting is the desert, traditionally the place of raw confrontation between human persons both with God and with the devil. It recalls Israel’s beginnings as a people, its time of formation by God and its wandering in the desert for forty years, utterly dependent on God for its sustenance. But more than that, it recalls both Moses and Elijah, each of whom fasted in solitude for forty days. Down through the ages, Saints and prophets have been shaped by the desert experience. From their stories, Monika Hellwig distills the biblical sense of a fast as an expression of humility before God, an attitude of radical dependence on God, and an act of total abandonment to God. And that was precisely what we see in this story, usually referred to as the temptation story, which tells us that Jesus was in the desert fasting for forty days and nights, tempted by the devil.

From our perspective, the temptations of Jesus, essentially on the three Ps – power, popularity and property – are not so much concerned with Jesus’ expectations with regards to His ministry as it is with ours. First, Scripture points us to the need to stop clinging to the idea of salvation by bread, by greater efficiency in money-making schemes, and by increased production, without at the same time taking into account the need to renounce our rights, privileges and entitlements in favour of others.

As we write, the news broke that the No.1 golf player in the world, Tiger Woods, has made a public apology over his sex scandals. What he said reveals that, amongst other things, the belief that one is entitled to do whatever one likes, without due respect for others and without due regard for boundaries, is at the base of serious social ills:

I was unfaithful. I had affairs. I cheated. What I did is not acceptable. And I am the only person to blame. I stopped living by the core values that I was taught to believe in.

I knew my actions were wrong. But I convinced myself that normal rules didn’t apply. I never thought about who I was hurting. Instead, I thought only about myself. I ran straight through the boundaries that a married couple should live by. I thought I could get away with whatever I wanted to. I felt that I had worked hard my entire life and deserved to enjoy all the temptations around me. I felt I was entitled. Thanks to money and fame, I didn’t have to go far to find them. I was wrong. I was foolish. I don’t get to play by different rules.

Then, Scripture points us to an urgent need to stop offering salvation by some form of magic tricks – in rituals or words proclaimed – without taking into account the real need of total conversion, beginning with the ones offering these means of salvation.

Third, Scripture points us to the dire need to cease all attempts to seek salvation through cleverly playing the “carrot and stick” game by both the governors and the governed in the Church – those who hold official authority and those who still look to official authority as the sole mediating channels of God’s saving power to them. For the answer which Jesus gave after the third temptation summarises the fruit of all praying and fasting: “You shall worship the Lord your God and Him only shall you serve.”

Today, this story provides the much-needed pointer to the path of right discernment where we can all read rightly what is worship of God and what is idolatry. And this is not just in the more obvious cases of images of demons and pagan gods that people set up on altars, but even more importantly, and certainly more insidiously, in the organized structures and the cultivated system of behaviour which, somehow, succeeds brilliantly in misleading people to acknowledge, and accept, absolute claims in anything and anybody that is not God. It is so very important, because Scripture reverses Lucifer who refused to serve God, and Scripture reverses Adam whose fall resulted from a wish neither to obey nor to depend on God. Clarity in this vision came about after Jesus had prayed and fasted forty days and nights in the desert. The early disciples had understood all this very well as the book of Acts, for example, records them fasting before they made important decisions (Acts 13:3, 14:23).

Some “golden” insights

In ancient Christianity, St. Peter Chrysologus, an early Church Father of the 5th century, known for his “golden-worded” sermons (hence his Greek title “Chrysologus”), gave a very wholesome teaching on prayer and fasting. He said:

- There are three things, my brethren, by which faith stands firm, devotion remains constant, and virtue endures. They are prayer, fasting and mercy. Prayer knocks at the door, fasting obtains, mercy receives. Prayer, mercy and fasting: these three are one, and they give life to each other.

Fasting is practised in all three world religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – descended from Abraham as their common spiritual father, and enjoys a venerable tradition. In the Christian season of Lent, the three pillars of penitential practice are prayer, fasting and alms-giving. Just as fasting without prayer is void of Christian content, prayer without fasting lacks any legitimate warrant for attention from the One to Whom the prayer is addressed. To these, must be added charity (or love and mercy). So the ancient saint would link the three thus: “Fasting is the soul of prayer, mercy is the lifeblood of fasting.”

- So if you pray, fast; if you fast, show mercy; if you want your petition to be heard, hear the petition of others. If you do not close your ear to others you open God’s ear to yourself. When you fast, see the fasting of others. If you want God to know that you are hungry, know that another is hungry. If you hope for mercy, show mercy. If you look for kindness, show kindness. If you want to receive, give. If you ask for yourself what you deny to others, your asking is a mockery.

According to this saint then, our three pillars of Lenten penitential practice are ultimately “a threefold united prayer in our own favour”. Our fasting will bear no fruit, he insisted, unless it is watered by mercy.

- When you fast, if your mercy is thin your harvest will be thin; when you fast, what you pour out in mercy overflows into your barn. Therefore, do not lose by saving, but gather in by scattering. Give to the poor, and you give to yourself. You will not be allowed to keep what you have refused to give to others.

A different kind of fast – “Daniel Fast”

If, however, you are like Archbishop Fulton Sheen who could not fast because “If I fast, I faint”, all is not lost. Of course, one never knows whether he was serious and meant what he said or he just did not wish to make a show of his fasting in public (thereby losing all credit) but would quietly do it in private so God alone would know. Anyway, we are referring to a different kind of fast called a “Daniel Fast”. A tradition stemming from that biblical character’s 21-day fast, it does not require a fast from food and drinks but it does require a selective fasting, and even in a rigorous way too. This is what Scripture says:

- In those days, I, Daniel, was mourning for three weeks. I ate no delicacies, no meat or wine entered my mouth, nor did I anoint myself at all, for the full three weeks [Daniel 10:2-3].

As we can see, one of the great things about the Daniel Fast is that you are not limited to any specific amount of food, but rather to the kinds of food you can eat. The Daniel Fast is limited to vegetables, fruits and water.

The background of the Daniel Fast is that Daniel and his three fellow Judaeans had been deported to Babylon when Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians conquered Judah (2 Kings 24:13-16). Put into the Babylonian king’s palace servant training program, they had to learn Babylonian customs, beliefs, laws, and practices. But Daniel, anxious over the fact that the eating habits of the Babylonians were not in complete agreement with the Mosaic Law, begged the chief eunuch to spare them from the defilement which would result if they had to take food and wine from the royal table. This is understandable, particularly with regard to the meat (which could vey well have been sacrificed to Babylonian deities which to the Jews would be false gods and idols). The chief eunuch was a man of goodwill, but he was concerned that he would incur the displeasure of the king who had assigned food for all, if the four Jews who did not eat looked “thinner in the face” than the other local youths who ate. On this, Daniel replied:

- Test your servants for ten days; let us be given vegetables to eat and water to drink. Then let our appearance and the appearance of the youths who eat the king’s rich food be observed by you, and according to what you see deal with your servants [Daniel 1:12-13].

The chief eunuch agreed. Ten days later, Daniel and his friends looked better and were healthier than any of the youths who had eaten their allowance from the royal table.

From this story, a few important points may be drawn for Christian living today, even during the season of Lent.

First, Daniel was a faithful adherent of his Jewish faith. He knew the king’s food was against his Jewish dietary laws. He knew he needed to do something about it and he did.

Second, a Daniel Fast is a spiritual commitment to God, for “Daniel was anxious not to defile himself” (Daniel 1:8).

Third, Scripture illustrates that faithfully practising one’s religion, one will be enabled by divine aid to triumph over the enemies.

Fourth, a Daniel Fast is not a total fast so nobody needs to “faint”, but it does involve selective fasting and Scripture is specific in its exclusion of meat and alcohol. It also specifies a rigorous discipline over a twenty-one day period.

And fifth, a Daniel Fast is directed towards a goal, which is religious.

Today, it seems that this “Daniel Fast” has become some kind of a mini-industry in this health-conscious age, with endless advice on what to eat and what not to eat and the benefits here and the benefits there.

As we see it, keeping a Daniel Fast meaningfully in the Christian sense must entail prayer and mercy, so that our goal in fasting is clearly fixed on getting closer to God by voluntarily denying the demands of our flesh. Our prayer life ought to be strengthened during this time. And our study of Scriptures ought to be undertaken with greater intensity so that we can see better and hear better, and in turn be able to act more justly, love more tenderly and walk more humbly with God (Micah 6:8). Christian fasting, after all, is a spiritual discipline that is meant to reinforce in each of us a greater reliance upon God in all things. At the end of the fast, we may hopefully receive from God a new lease of life, on a renewed spiritual strength to overcome those inclinations which control our lives and draw us away from dedicating ourselves to God.

If, by the grace of God, we succeed in doing that, individually or with mutual support in a group, we may hopefully be able to reach the kind of genuine fasting elaborated in Isaiah 58. There, God made clear that there is no point in fasting if our energy is expended on money-making, oppressing workmen, or striking the poor. Fasting like that would not be heard on high. Nor would hanging one’s head like a reed or lying down on sackcloth and ashes. The fast that the Lord God desires to see is one that breaks unjust fetters, relieves people’s burden, sets the oppressed free, shares bread with the hungry, shelters the homeless poor, and clothes the naked (Isaiah 58:3-8).

Keeping a Daniel Fast may then not only be a weight-losing or a physical cleansing of our bodies of toxins by excluding from our diet meat, alcohol, coffee and so on, and eating only vegetables and fruits and drinking only water. It will also be a spiritual cleansing of our souls from greed and selfishness and a whole possible list of spiritual enemies. Furthermore, keeping a Daniel Fast is a useful occasion, individually or in groups, to fast and pray for clarity and direction whenever there is an individual or communal crisis (or just an important individual or communal project), and not necessarily in the Lenten season. It is a time of heightened awareness of the illusions of our own self-sufficiency, a turning away from our own devices, opinions, and strength, and a turning to God once again. There, hopefully, we may again find ourselves and our missions in God’s scheme of things, whatever our stations in life.

We wish you all a very fruitful Lenten journey.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, March 2010. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.