Reflections on a Pauline Pilgrimage to Turkey [11]

“You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbour and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” [Matthew 5:43-44].

[1] The Gallipoli Peninsula. [2] Drawings by Major Hore. [3] ANZAC cemetery.

Gallipoli was a welcome break in this Pauline pilgrimage to Turkey.

We have heard so much about Gallipoli. We have sat through a TV live broadcast of the ANZAC Day celebration. And we have read up on this important historical event before. So when a request came from an Australian couple in our pilgrimage group, Max and Annie, for it to be included in the itinerary, we heartily supported it.

The Battle of Gallipoli took place at the peninsula of Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire (modern day Turkey) between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916, during the First World War. The British and French mounted a joint operation to capture the Ottoman capital of Constantinople and secure a sea route to Russia. The operation failed, with heavy casualties on both sides. What the Gallipoli campaign did was to profoundly impact the consciousness of all nations involved. In Turkey, the battle is perceived as a defining moment in the history of the Turkish people, firing as it did the Turkish War of Independence and the foundation of the Republic of Turkey eight years later under Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk), himself a commander at Gallipoli. As the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) undertook their first major battle, the Gallipoli Campaign has since become the singular galvanizing event that awakens the national consciousness in both of these countries. ANZAC Day, 25 April, is their most significant commemoration of military casualties and veterans. As pilgrims travelling with four Australians in our group, we were conscious and respectful of both the sacredness and the tenderness of their memories.

Concerning the details of the war, however, we are neither qualified nor inclined to comment. Browsing through various reports and comments, our impression is that history can be a strange creature, depending on who writes it. Before the Gallipoli campaign even got started, Lloyd George had prophetically written: “Expeditions which are decided upon and organised with insufficient care generally end disastrously.” Overall, there is no denying that the Gallipoli campaign, vehemently proposed by Churchill as a strategy to weaken the opposition, was a disaster of the first order. The tally of Allied casualties was over 200,000, and while the number of Turkish casualties is not clear, it is generally accepted as being equally horrendous.

Standing on a cliff overlooking a beach at Gallipoli, we were infused with sensitivity to the treachery of the terrain and the drama of the surrounding, but even more, with the tragedy of war. What was infinitely more captivating of our mood was the human factor – the effects wars had on the people, and even on generations that came after them. And this is resonated in a refreshing way in a recent Chinese ancient-war movie, The Warring Sates.

In The Warring States [戰國], we have a Chinese movie featuring the brutal battles and raging melodrama set in the 5th to 3rd centuries B.C. China, the Warring States Period of Chinese history. The story-line hovers round the states of Qi and Wei, leaving aside the five other warring states. The singular item of the movie which continues to detain us in reflection is a clip that comes right at the end. It is the statement of inner conviction uttered by Sun Bin, the favourite student of Sun Tzu (孫子) – the world renowned military strategist. In some business schools and military colleges in the West, The Art of War [or Sun Tzu’s Military Strategy孫子兵法] is compulsory reading. Sun Bin led the army of the Qi Kingdom in a brilliantly successful military campaign against the vastly superior force of the Wei Kingdom. His strategy not only won the battle but decimated the entire enemy army. On seeing the insane devastation to human lives, far from celebrating a brilliant victory of which he was the architect, Sun Bin in utter despondence said, “I hate wars!” and jumped off the cliff to his own death. All his life, he had wished that soldiers would all go home to till their lands and raise their families in peace and harmony. There are no winners in wars, only a diminution of our humanity.

And that was precisely the sentiment we each felt at Gallipoli: “I hate wars!” Lines of tombstones of young men testified to lives wasted and futures snuffed out, all on account of politicians and warlords who made plans of aggression and issued orders. They were the ones to decide – a mantra that exudes from the mouths of many in all sorts of power-position today wherever we turn, in church as in secular society. They have directly caused all those vicarious deaths, while their own lives [and in all probability their own sons’ lives too] were never actually put in jeopardy in the battlefields. And when we factor in our reflections the death of tens of thousands of innocent civilians in Iraq the last few years as a result of a groundless Western invasion, we must wonder why the President of the United States who ordered the invasion is not charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity.

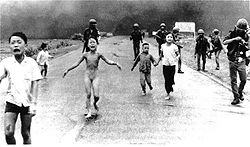

Gallipoli brought back memories of our visit to the war museum in Ho Chi Ming City some years back. As we followed the display of photos and write-ups, emotions gradually welled up and the eyes began to fill. What is it with this creature of the Good God called “human being” that he can be so inhumanly atrocious towards other humans? And when we reached that familiar iconic picture of a naked little girl running away from a napalm bomb, crying and in hysteria, with her back burning, and panic, pain and terror written all over her face, we just had to suspend the tour. Unable to proceed without a pause, we went to a little side-garden outside the building to shed tears, to mourn human suffering in the hands of atrocious American warlords, and to breathe some fresh air, before we could resume our tour.

[1]The Warring Sates, a Chinese ancient-war movie. [2] The Art of War, in a classical bamboo book. [3] 8 June 1972: Kim Phúc, center left, running down a road near Trang Bang after an American napalm attack.

- The photograph of Kim Phuc, the so-called Napalm Girl, that appeared in newspapers during the last years of the Vietnam War – June 9, 1972 to be precise – shocked the world and still stands as one of the war’s central icons. The horrifying image of a nine-year-old South Vietnamese girl running naked down a road away from an American napalm strike, her child’s body on fire, her arms outstretched, her face contorted in pain, captured international attention. The photograph, which won a Pulitzer Prize and made the wounded child a symbol of the human capacity for atrocity, belongs to a small number of iconic images that have come to represent the horrors of the war’s casualties – and, indeed, of war itself. Kim Phuc, however, survived the devastating burns inflicted by napalm. More than two decades later, living in Canada, she became famous again in the mid-1990s through a second photograph and a speaking appearance on Veteran’s Day at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1996. This new photograph of Kim as the mother of an infant son, as well as her own repeated commentary on it, relocates her in the culture of trauma and testimony that has grown more and more powerful in the United States since the end of the Vietnam war. Almost twenty-five years after the traumatic event of the napalm bombing, the girl’s silent scream that spoke eloquently to the war’s opponents is given voice by the language of trauma and recovery; the girl-victim of war’s inhumanity becomes an adult survivor, who speaks publicly of her past experience and her hopes for peace in the future.’

When nationalism becomes more important than the kingdom of God, Christians do the right thing by questioning the righteousness of every military campaign. When Christians are conscripted for war against their conscience, the right thing to do is civil disobedience. There is always a war waging in all of us, between what is good and what is evil. The message of peace in the Sermon on the Mount was directed to Jesus’ disciples. And what the Lord taught on the mountain where he preached the great Sermon [Matthew 5-7], he lived to the full on the other mountain, the Mount of Calvary. Non-violence is always more appropriate than war and attrition.

On April 4, 1967, at the height of the Vietnam War, Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke against the war in a fury-filled sermon at the Riverside Church in New York. Two of his most powerful, prophetic and daring lines in that sermon deserve to be repeated over and over:

- “I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today, my own government.”

- “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

Assuredly, these daring lines offended many people at the time. There is no prize to be won for correctly guessing that swift kicks were quickly aimed at him by the establishment media and other guardians of probity. Today, those attacks only help to raise the prophetic status of such a great man.

What the “OCCUPY” movement that spreads from the Tahrir Square in Cairo to the cities across the United States of America witnesses for us, is a remarkable phenomenon of a spontaneous and leaderless uprising. Not unlike spontaneous combustion, people are spontaneously galvanized towards a peaceful but explosive impact. The People, especially young people, realizing that the economic inequities in their societies come from greed and corruption, are refusing to put up with it anymore and are prophetically calling for justice. In the context of this post, and in line with what we have quoted from Martin Luther King, Jr., we hope people across the world would sooner make the connection between war expenditures abroad, and poverty at home, occupy peacefully, and demand change. But even more, we dearly hope that before they highlight the economic crunch at home, they first protest the killing of innocent civilian lives abroad by way of “collateral damage” simply because it is wrong! Today, this damage has become colossal on account of efficient technology that vastly increases the damage on the enemy side while dramatically decreases the loss of military personnel on one’s own side. We need to factor into our consideration the destruction of families, the economic hardships, the loss of parents, children, the destruction of society, and the string of traumatic and alienating fruits of these cruelties.

At the end of the day, we think it helpful to key into the following, amongst other, sentiments:

- We are designed to fall short of answers.

- We are called to yield to the work of Christ within us, to soften our hearts in all human dealings.

- We must see militarism as being radically incongruent with everything that Jesus ever did.

- We are to be part of the global movement for peace and reconciliation, to turn weapons into ploughshares.

- We are to reject violence of any sort, to walk the way of non-violence in personal lives.

- We are all structured to weep in compassion.

- We are destined to need each other and God.

- We are to awaken to our fundamental Christian mission to promote justice and peace.

Christian commitment is not only to reject or protest war, but to also demonstrate how nonviolence can actually solve the problems that war claims to and does not. This will increasingly be a serious test of our Christian imagination.

At Gallipoli, therefore, the moment we treasured the most was when our Australian couples shared their Gallipoli-cookies with the whole group, starting with our Turkish guide, Mr Tuna. It was good to see Australian and Turkish representatives sharing Gallipoli-cookies, at Gallipoli.

“Peace,” wrote Baruch de Spinoza, “is not an absence of war. It is a virtue, a state of mind, a disposition for benevolence, confidence, justice.”

The Second Eucharistic Prayer for Masses of Reconciliation, before the new translation, sums it up well:

“ Your Spirit is at work

when understanding puts an end to strife,

when hatred is quenched by mercy,

and vengeance gives way to forgiveness.”

[Note: We are taking a short break from this series of “Reflections on a Pauline Pilgrimage to Turkey” in order to accommodate requests from parishioners of St Ignatius’ Church, Petaling Jaya. The next three posts will feature the transcripts of talks we gave at their parish feast day celebration in July this year. They provide some thoughts which we hope may be useful for the Advent reflection. Our Pauline Pilgrimage series shall resume in the new year.]

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, November, 2011. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.