“The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham.” (Matthew 1:1)

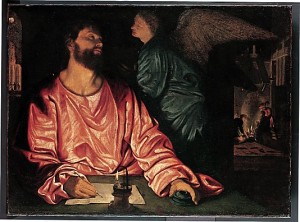

[1] The Lindisfarne Gospels: a 7th cent. AD illustration of the evangelist Matthew and his symbol. [2] Saint Matthew and the Angel Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo. Savoldo’s painting shows Saint Matthew—inspired by an angel, the traditional symbol of the Evangelist—writing his gospel. In the background are two scenes from the Saint’s life: (right) the Saint receiving hospitality from the eunuch of the Queen of Ethiopia, and (left) the Saint’s martyrdom, which took place in a church built for him in Ethiopia. [3] St. Matthew and the Angel by Rembrandt.

The Church celebrates the feast day of Saint Matthew the Evangelist on September 22. The first book of the New Testament is attributed to his name.

The Gospel According to Matthew is not just one of the four canonical gospels, one of the three synoptic gospels, and the first book of the New Testament. It does not only tell of the life, ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. The longest of the four texts, Matthew’s Gospel is known as the “ecclesiastical gospel” because, of the four written forms of the gospel, it is the only one which mentions the church as such – once in Matthew 16 where it is concerned with church order (Peter) and twice in Matthew 18. Moreover, Matthew is concerned with church teaching (the Great Commission in Matthew 28, the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5-7…) For centuries the most used gospel text in all the churches, Matthew’s Gospel has been the most influential in shaping the collective memory of all Christians about their Lord down through the ages.

Matthew’s Gospel was known to the point that it entered into the European Christianised culture. And in so far as the two manifestations of any civilized culture are its religious traditions and its language, Matthew’s gospel played a key role in shaping Christian consciousness as the faith spread from Europe to the rest of the world. To cite an example, we know the “Our Father” according to the version in Mathew 6. We are unable to reproduce by memory the version of Luke who simply says “Father”. Similarly with the Beatitudes: we are taught there are eight and that’s according to Matthew, while Luke has only three. Influenced by Matthew, we speak of Jesus’ forerunner as “John the Baptist” who is referred to as “John the Baptiser” according to Mark. The term “pharisaic” in the dictionary means “hypocritical” as found in Matthew 23: “You Pharisees …. you hypocrites!”

The most important statement in the manuscript tradition about the gospel of Matthew was made by Papias of Hierapolis, a bishop of the early Church, canonized as a saint. Writing in the first third of the second century. he said Matthew “compiled the words of the Lord in the Hebrew dialect” and each one interpreted them as he or she could. Generations of scholars saw this description of Matthew as an actual description of the longest gospel text. Three features in Papias’ text deserve attention.

- 1. “Compilation of the Lord’s Words”: Matthew as a gospel-writer was a “compiler” of oral traditions. Like the other evangelists, he was an editor of existing materials known in faith communities of the time. Unlike Mark or Luke, Matthew has more discourse materials, largely collections in the five major sermons – On the Mount [5-7], Missionary [10], Parables [13], Ecclesiastical Discourse [18], Woes to Pharisees [23], followed by Discourse on the Last Things [24-25]. In sum, nine chapters in Matthew are entirely discourse materials.

- 2. “In the Hebrew Dialect”: Hebrew, in the first century, was a sacred language. The Torah was written in Hebrew. Later, as prayer and instructions developed, the prophets and wisdom writings were also read in Hebrew in the synagogues. But Jesus and his followers spoke Aramaic, a language like Hebrew that belonged to the Semitic family.

- 3. According to the interpretation of Papias: Matthew was a first century Palestinian who understood Aramaic. According to the interpretation of Papias, then, it is likely that Matthew wrote the gospel in Aramaic. Since Mark and Luke wrote in similar pattern as Matthew, Papias’ interpretation led others to conclude that Mark and Luke must have made use of the text of Matthew translated and available and used everywhere Christians were to be found.

In the West, therefore, Matthew’s gospel, listed as first of the four gospels in the New Testament, was considered to be the source of Mark and Luke. So Saint Augustine of Hippo [354-430 AD] in his harmonization of the gospels, proposed that Matthew was the oldest, Mark was a digest of Matthew, and Luke was an expansion of that digest. The Augustinian hypothesis assumed the order of composition to be Matthew, Mark, Luke. Given the stature of St Augustine in the West, the attribution of the gospel text to one of the Twelve, and the fact that it has the most information on Jesus Christ, St Augustine’s view remained unchallenged until the eighteenth century when J.J. Griesbach produced a synopsis of the gospels in which he maintained that Matthew was the source of Mark and Luke, but that the order of composition was actually Matthew, Luke, Mark. Since 1774 when Griesbach printed the first synopsis, that is, the gospel texts in parallel form, any student studying the Synoptic Gospels in a serious way has to deal with the “synoptic fact”.

There are three dimensions in the Synoptic fact.

- First, the structure of the three gospels is remarkably similar.

- Second, the selection of events narrated is also remarkably similar.

- Third, there is also a great similarity of details.

A scholarly consciousness of this fact marked the dawn of the historical-critical era in Biblical studies. A whole new hypothesis of the priority of Mark came into being after decisive debates in the 1830s and 1860s. This basically goes back to Karl Lachmann who died in 1851. Unconvinced by arguments of Mark’s dependency on Matthew, Lachmann suggested in 1833, after carefully studying the sequence of events narrated in all three gospels, that Matthew and Luke only have the same plot to the extent that they share that plot with Mark. This led him to argue that Matthew and Luke used the Markan structure and “interpolated into the plot”. The last periscope where there is agreement between all three gospels is The Woman at the Tomb. At this point, Mark’s gospel ends whilst Matthew and Luke continue their accounts which are not parallel. Without the Markan structure, they follow their own imagination. So Lachmann proposed that Mark constituted the pre-existent text. By 1835, observed Raymond F. Collins [1], the study of the gospels had moved from the pulpit to the lecture theatre. This marked an important milestone in scholarly study of the Bible. From then on, study had moved from Church with its incumbent ecclesiological tradition to the relative freedom of the academia. However, on account of centralized ecclesiastical control, the Catholics would straggle, stagnate and lag behind the Protestants in Biblical studies for a good two hundred years until the late first half of the twentieth century. Only then did critical Biblical studies in Catholic circles took off and advanced by leaps and bounds.

From then on and to this day, even though there has been no lack of scholars who continue to defend the Matthean priority, the majority view has shifted solidly to Mark as being the first amongst the Gospels to have been written.

Coming from Leuven, Belgium as we do, we ought to mention that Professor Frans Neirynck of the Catholic University of Leuven has in recent decades been the leading authority on the “Markan Priority”. In this regard, he has an article which is readily accessible. Titled “Synoptic Problem” , this article appears on pages 587-595 of The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, edited by Raymond E. Brown et al. It addresses the literary relationship between the three Synoptic texts.

Is the “Synoptic Problem” relevant to us in any way today? The answer is affirmative.

First, it is relevant for the study of the historical and literary questions of the composition of the three gospel texts. Apart from leading us to some understanding of the literary sources of our foundational Scripture texts, this study has immediate bearing on our understanding of the history of early Christianity.

Second, a historical-critical method, according to Raymond E. Brown, can help to keep the Church honest. One may illustrate through a close look at some minor details concerning the chosen apostles in the Synoptic Gospels. For example, scholars estimate that Mark was written around 70 AD while Matthew was written between 80-90 AD, by which time the “ecclesia” had begun to crystallize. Faith had begun to take on the flavor of an organized religion, and a felt-need had arisen to protect the good name of the leaders, so that lying a little bit about it would seem justified. Let’s take two examples.

- The episode of the “Stilling of the Storm” is a telling story where the Markan Jesus scolded His apostles as having “no faith” [Mark 4:35-41] but the Matthean Jesus only chided them as “men of little faith” [Matthew 8:23-27]. From Mark to Matthew, after ten or more years, the faith of the same apostles had grown a little in the hands of Matthew the Evangelist! Why? Once the “ecclesia” was in place, it was “not nice” to describe the leaders as “men of no faith”, even if the Lord said so (originally, because Mark was written first)!

Rembrandt, Christ in the Strom on the Lake of Galilee.

Rembrandt, Christ in the Strom on the Lake of Galilee.

- In connection with the episode of “The Third Prediction of the Passion”, Mark says James and John [to the indignation of the rest of the Twelve] approached Jesus and asked for His left and right hand seats [Mark 10: 32-45]. To preserve the “good name” of the two apostles, however, Matthew transferred the blame to their mother, making her the “culprit” of the unseemly act of seeking privileged positions for her sons [Matthew 20:17-28]. Mothers being mothers, we do not think the mother of the two Zebedee brothers, with her innate DNA to make sacrifices for her children, would have minded. The point, however, is that within a space of 10 or so years, Matthew had deemed it fit to do some cosmetic cover-up, failing to realize that you can cover up the truth for a while, but not for long, and never against the original Word of God.

On that Word, perhaps it is worth our while to recall two things from what the Lord said in response to James’ and John’s aspiration for power and position in the Church:

- [1] Giving all sincere followers of His a lesson on what it means to follow after Him, Jesus taught that true discipleship entailed making sacrifices. In Mark’s gospel, Jesus told James and John that to really sit in glory with Him, they would have to drink the cup of suffering that He was going to drink, and they would have to undergo the baptism with which He was baptized, both of which apparently refer to the agony He was to endure at His crucifixion.

- [2] In an even more practical way relevant for all times, but paid more lip-service to than any other teachings of the Lord, Jesus taught about servant leadership. He said to the Twelve: “You know that those who are supposed to rule over Gentiles lord it over them, and their great men exercise authority over them. But it shall not be so among you; but whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be slave of all.”

Third, the “Synoptic Problem” is relevant to the movement of thought within early Christianity. Take, for instance, the first of the Beatitudes[Matthew 5:3; Luke 6:20b]. In Matthew, it is “Blessed are the poor in spirit” whereas in Luke it is “Blessed are you poor”. If Matthew was written first, meaning those Jesus considered blessed were those with the right religious disposition, then Luke’s gospel text had evolved towards a concern for social justice. The Christian understanding would have moved from a religious understanding to a social movement. If, however, Luke came first, then Matthew spiritualized the Christian concern. There is a big difference between the Matthean notion of a simple lifestyle and the hardship of poverty mentioned in Luke. Thus, in studying the Synoptic Problem, we grow in understanding and knowledge of the development of early Christian theology.

[1] The chapter on Source Criticism in Raymond F. Collins’ very popular Introduction to the New Testament [London: SCM, 1983] is useful reading on the subject matter of this post.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, September 2012. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.