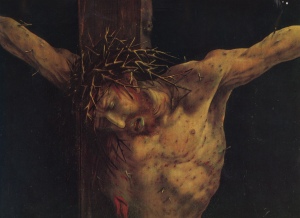

“And at the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?’ which means, ‘My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” [Mark 15:34].

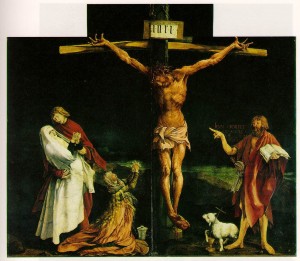

Matthias Grünewald, Crucifixion, from the Isenheim Altarpiece.

Salvation is won through the Cross. On that we all agree.

For every Christian, the Cross of Christ is the most powerful symbol of salvation. It is without doubt the most universal of all Christian symbols. The sad thing is, the Cross of Christ is, at the same time, the most desecrated.

As Christians, the Cross locates us and teaches us who we are. It connects us to Jesus. Deep down, while Christians appreciate that the Cross is an instrument of torture, they nevertheless feel strongly that it is the foremost sign of God’s mercy and Christ’s suffering on behalf of sinful humanity. It is like a signing device through which we look at the world. The Cross is so much a part of our Christian consciousness that when we travel to a new place and we want to pray, we even look out of a hotel room and search for something that resembles a cross to render our focus – a telephone pole, a TV antenna….

And yet, behind all this, we are ever conscious too, that Christians have always kept an ambivalent relationship with the Cross of Christ. Everywhere we turn, the Cross casts a shadow. We need only take a brief look at a few issues to see the shadow.

[1] A Cross without Christ?

First, there is a pair of seemingly innocuous and yet profound flip-sided questions. Can we have the Cross without the Christ? Can we have the Christ without the Cross?

A few decades ago, long before the present day “communist” China has emerged as a towering economic giant that threatens the dominance and dampens the insolence of the “democratic-capitalist” West, Archbishop Fulton Sheen used to speak of the suffering Chinese people as those who had the cross without the Christ.

The opposite, we are afraid, may more accurately describe the reality of faith-teaching and faith-practice in many Christian churches across the globe of our own time. There, professed Christians commonly want the Christ without the cross. Those preaching the prosperity-gospel and managing “blessed” churches – “come to us and you will prosper” type – are easy targets for criticisms in this regard.

Then you have those Christians, quite misinformed, who behave like grassroots zealots. They visit hospital wards seemingly doing corporal works of mercy. But when they come across a Catholic mother sitting at the bedside tending to a sick child, however, they would not hesitate to remind the wearied mother that it was not right to wear a crucifix – a cross that has Christ hanging on it – because, they vehemently claim, Christ has risen and is victorious. “Christ is no longer on the cross at Calvary,” you hear them insist.

One ought to be able to douse such misinformed, hospital-ward-crawling zeal at two levels.

First, at the coffee-shop or pedestrian level, one could return-serve these zealots with the flat retort that they should not be wearing a cross at all, because the wood of the cross on which Jesus was pinioned on Calvary has long rotted. In other words, even the cross is no longer at Calvary, never mind the Christ.

At even this pedestrian level, one could already make the connection that the Cross or the Crucifix that one wears round the neck is meant to be a Christian symbol. As a symbol of salvation, what meaning can the Cross possibly offer without the Christ? A life of meaningless human suffering under the old communist regime, Sheen would say. In any oppressive regime, in other words, Christ is absent; God is absent.

Second, at the theological level, therefore, our minds turn at once to the possibility of a deeper understanding of this primary symbol of our salvation. There, a key question inevitably surfaces: Why did Christ have to die on the cross? Hermen-Emiel Mertens, our professor of Christology at Leuven, Belgium, suggests that it’s not the cross that we should focus on to get answers for salvation, but the One Crucified on the cross. His book on this topic is titled Not the Cross, But the Crucified: An Essay in Soteriology [Louvain:Peeters Press; Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans, 1992]. Attention is wrongly focused when the target is the mere cross. Christians meditate on He who hangs on the cross. Without the Christ, the cross is meaningless suffering.

We join hands with the “zealots” in proclaiming that the Cross is truly beautiful. We would insist upon them to accept that the cross is not beautiful in itself. Foisted on Jesus of Nazareth, the cross represents the power of the Roman empire, a power that is always opposed to the way of Christ. Yet, we do insist that the Cross is truly beautiful, for the beauty is in the Crucified One who chose to endure unjust suffering, who chose the way of peace rather than violence, and who chose death in love, living to the full the depth dimension of God’s will: For God loved the world so much that He gave His only Son [John 3:16].

So now, we know, the tomb is empty, for the grave cannot hold God’s Messiah down! We can begin to key into St Paul’s teaching in Romans 5:10 – “For if, while we were God’s enemies, we were reconciled to him through the death of his Son, how much more, having been reconciled, shall we be saved through his life!” In the Cross, we see the beauty in Jesus’ life which models for us what it means to love our enemies even as it humbles us with the resounding reminder that we all were God’s enemies.

[2] The Cross Is Meaningless without Suffering

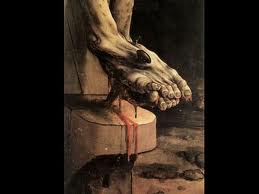

Looking closely at the Crucified One on the Cross was what the artist Mathias Grünewald did. In his famous Isenheim Altarpiece of the early 16th century, he does not allow us to run from the fact that the crucifixion was cruel and evil. Christ did not die an easy death. It was not pretty! Grünewald demands that we look at that ugly picture and not turn away. As he portrays the Suffering Servant of Yahweh crucified on the cross, the artist wants us to make no mistake about the reality of the cross as dark, evil and harsh. This artist would turn in his grave were he to see people wearing huge crosses in gold or diamond-studded or colourfully and artistically designed purely for decoration and high-end fashion-commerce.

The Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald, 1506-1515.

The heresy of the likes of the preachers of the prosperity-gospel lies in its utter denial of the inevitable cross in every human life. An authentic Christian life has got to be modeled after the Paschal Mystery of the Lord – His suffering, death and resurrection. The journey moves from pain to hope, from suffering and death to resurrection. This is the Christian model. Good Friday is “good” on account of Easter Sunday, but there would not be the Easter Resurrection without the Friday Cross. It is a counterfeit Christianity that claims Christ’s victory but ditches his suffering. It is a con artist who lures people to Christ’s blessings free from the cross.

The modern day culture, however, makes for a sharp contrast with the Christian model. So Ronald Rolheiser observes:

- Our age is characterized by impatience, by an unwillingness to ache, to long, to yearn, to sweat lonely tears in the garden as we wait for new birth. More and more, we are becoming a culture that is incapable of remaining within emotional suffering.

What the followers of Christ must not do is to suppress the inevitable hard and dark side of human existence. On this, Karl Rahner, SJ, has made a serious indictment:

- “Christianity has placed the cross on the altar, has hung it on the walls of Christian homes, and has planted it on Christian graves. Why? Evidently it is supposed to remind us that we may not be dishonest and try to suppress the hardness and darkness and death in our existence, and that as Christians we evidently do not have a right to want to have anything to do with this aspect of life until we have no choice.”[1]

[3] Christ’s Victory on the Cross Did Not Involve Power and Might

Christ’s victory on the Cross was non-violent but wrought in love. It is an utter abuse of the Cross whenever it is used in service of violence, power and might.

Vision of the Cross, by Raphael, 1524.

Vision of the Cross, by Raphael, 1524.

In 312 AD, Constantine is reputed to have seen a Fiery Cross in the sky on the eve of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. It was allegedly interpreted as assuring him of victory in the name of the Christian God. This seemed to account for his patronage of the Christian Church after the battle. To this day, this so-called vision and its accompanying interpretation remains theologically problematic.

Then we have the Crusaders of the 11th – 13th centuries who prided themselves as gallant followers of Jesus of Nazareth. “Christus est Dominus” – “Christ is Lord” – was their battle cry. They apparently meant by “est Dominus” a life of militant knighthood, devoted to conquest by violence. However, when “Christus est Dominus” was uttered to authorize the cleaving of the skulls of the “infidels”, these words on the lips of the Crusaders were false and were a mere slogan of a very zealous and violent militia. Christ is Lord, but not in that murderous fashion. Christ is the Lord, the Redeemer, through suffering service. Against this fundamental Christian belief, the “Christus est Dominus” as uttered by the crusaders was simply inconsistent.

In the USA, the Burning Cross is an infamous hallmark of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), used to terrorise their intended victims. They claim that lighting the cross is a symbol of their faith. The fire signifies Christ as the light of the world. Light drives away darkness and gloom. Fire cleanses and purifies. More importantly, they believe the fire symbolizes power and glory, and setting the cross on fire serves as a warning to those that dare interfere with a pure race of white supremists movement. These are self-confessed ultra-right nationalists, who are proud to be ‘White/American/Christian’. And yet, Jesus was not an American, but was a Middle-Eastern, Palestinian Jew. More importantly, these messed-up men have completely missed the point of the Cross as the ultimate symbol of the Suffering Messiah who died in the hands of powerful political and religious tyrants.

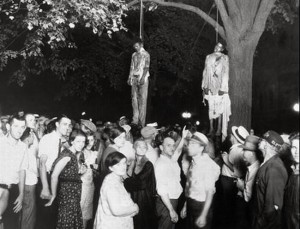

[4] The Cross Is at the Same Time the Lynching Tree

[1] Crusaders. [2] Ku Klux Klan cross burning.. [3] Lynching of Young Blacks. Aug 7, 1930. Photo by Lawrence Beitler.

Finally, we come to a most excruciating point, the very dark and shameful chapter in the history of the American nation when white people regularly murdered black people by publicly hanging them on a tree.

In the provocative words of author James Cone:

- The cross and the lynching tree interpret each other. Both were public spectacles, usually reserved for hardened criminals, rebellious slaves, and rebels against the Roman state and falsely accused militant blacks who were often called “black beasts” and “monsters in human form” for their audacity to challenge white supremacy in America. Any genuine theology and any genuine preaching must be measured against the test of the scandal of the cross and the lynching tree.[2]

The Christian teaching of redemption in the Cross is by no means an easy one to absorb or to teach. One has to have a rich life experience and a powerful religious imagination to discover life in death and hope in tragedy. And in the words of Reinhold Niebuhr:

- Christianity is a faith which takes us through tragedy to beyond tragedy, by way of the cross to victory in the cross.

What we find extremely helpful in James Cone’s teaching is the call to drop our false pieties with regard to the Cross. We want to rise with him and scream every time someone romanticises the Cross and ignores its cruelty: “You shall not forget!” Just as the crucifixion was a first-century lynching, the lynching tree of America is a modern day lynching. In each case, it was a cruel, agonizing, and contemptible death. As a Christian theologian, Cone can insist that:

- the cross and the lynching tree need each other;

- the cross can redeem the lynching tree, and thereby bestow upon lynched black bodies an eschatological meaning for their ultimate existence; and

- the lynching tree can liberate the cross from the false pieties of well-meaning Christians.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, April 2012. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.

[1] Karl Rahner, Foundations of Christian Faith [NY: Crossroad, 1992], p.404.

[2] A lecture given by Professor James Cone at the Harvard Divinity School on October 19, 2006 titled “The Cross and the Lynching Tree”.