For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes. Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord. [1 Cor 11:26-27]

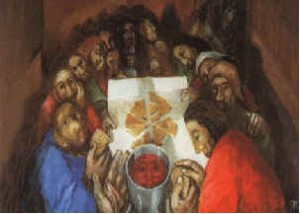

[L] Paul Writing, by Jeff Ward. [M] St John Chrysostom, 4th century A.D. [R] Sieger Köder, The Last Supper.

When something like the Lord’s Supper, which ought to benefit the community is actually harming it, Paul is understandably upset and his response is likely to be quite scathing. His pastoral solution to the problem of abuses at the Lord’s Supper in ancient Corinth [1 Cor 11:17-34] has much to teach us concerning what we call the Eucharist.

The Background

For Paul, when believers gather for the Lord’s Supper, they ought to know that they do not do so for a Greco-Roman meal. Instead, they are gathered for an event that serves the triple function of solidarity [koinonia], commemoration, and proclamation that brings with it a spiritual blessing in anticipation of the [eschatological] banquet of salvation on the last day.

Contrary to Paul’s vision however, the gathering in Corinth represented a totally different triple-reality: division, amnesia, and betrayal. For an issue as important as this, Paul cuts to the chase and pronounces divine wrath upon the transgressors. Whatever they think they may be doing at the table of the Lord, they are, according to Paul, celebrating anything but the supper of the crucified, present and coming Lord.

The actual situation was something like this [11:20-22]. The believers whom Paul left behind in Corinth as he moved to Ephesus, came from a wide spectrum of the society. The community gathered at the Lord’s table represented a variety of socioeconomic groups. They assembled at a wealthy member’s house. The richer ones were likely to come early and they would sit in the dining room [triclinium], while the poorer ones were likely to arrive much later after work. The rich and early comers would not be waiting for the poor latecomers but, joining the house owner for what would amount to a private meal, went ahead with their consumption of better food and agreeable alcohol. As a result, when the poor latecomers arrived and gathered not at the triclinium but at the atrium, they would by then be quite hungry and yet find little or nothing to eat even though their rich counterparts were all filled and some were even visibly inebriated.

What was supposed to be a ritual gathering of believers, the body of Christ, for the Lord’s Supper where the bread and the cup were supposed to be the heart of the experience [“This is my body; this is my blood; do this in memory of me”] had all but deteriorated into a private party of the Corinthian elite, in total disregard for the needs of the poor, the sanctity of the body and blood of the Lord, and the memoria of what the Lord had done.

In what we now have as Paul’s first canonical correspondence to the Corinthians, we see him stress three dimensions concerning the Lord’s Supper.

Significance of the Lord’s Supper at Three Levels

1. Koinonia

The Lord’s Supper is never intended to be a private meal, for the elite or otherwise. It is a coming together in solidarity and fellowship. This fellowship is in the first place communion with Christ and through and because of him, communion with each other. This vision is famously expressed by Paul in 1 Cor 10:16-17:

- The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a sharing in the blood of Christ? The bread that we break, is it not a sharing in the body of Christ? Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread.

Furthermore, Paul stresses that there is to be a special solidarity with “those who have nothing” [11:22], for they are the special object of God’s choosing in Corinth [1:26-31].

Bible studies at this level compel us to see that, for Paul, the real presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper [what Catholics call the Eucharist] lies in the members of his body. For Paul, Christ and church are almost inseparable, save that linguistically speaking, at the table of the Lord, the ecclesial body of Christ is gathered to celebrate the Eucharistic body of Christ.

With that understanding, it is no wonder that when Paul warned against eating and drinking “without discerning the body”, he was not so much stressing “the real presence in the Eucharist” as he was vehemently insisting upon the need to discern and honour church members as the body of Christ. What was done against those poor members was done against Christ; their actions were anti-Christ.

With depth perception of the truth in this Pauline vision, St John Chrysostom (c. 347–407), Archbishop of Constantinople, said emphatically:

- “Those who fail to recognize Christ in the beggar at the church door

will not find him in the chalice.”

2. Memoria

The Lord’s Supper is an event of memory – of remembrance.

The Lord’s words of institution focus on the phrase “in remembrance of me” [11:24-25]. To remember Jesus is to recall the significance of his suffering death and acknowledge what God has done for us in him.

For the Jews, as it is for us as well, “remembering” is not just about recollecting some event that happened in the past. It is in greater depth about faithfully responding to God and God’s past saving actions, which are made real and present and effective once again in the here and now in the very act of faithful remembering.

What St Paul meant was required of the first-generation Corinthian converts, as Holy Scriptures must now mean for us in the twenty-first century is that, whenever we celebrate and worship at the Lord’s table, we are to remember Christ’s self-giving in death and in so remembering, to participate in it as a present reality not just at the table of celebration, but after leaving the table as well, by living faithfully and appropriately in the shadow of the cross.

3. Proclamation

The celebration of the Lord’s Supper is to remember him in a special way, that is, to “proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” [11-23-26]. This celebration entails not only eating and drinking, Paul stresses, but the very presence and participation on the part of the believers is at the same time a proclamation of Jesus’ death until he comes again.

In Ben Witherington III’s words: “It looks to the past, present, and future [and is] part of the Christian witness to the crucified, risen, and returning Lord.”

One gets the sense from Paul’s first canonical epistle to the Corinthians that for him, not only the unbelievers but also and even especially the so-called believers need to have the cross proclaimed to them! To be sure, Paul throughout the epistle is adamant that a community that forgets the cross forgets its identity – as followers of the Crucified but Risen Lord. A community that forgets the cross, that is de-centered from the cross will, like the first convert- community in Corinth, marginalize the weak.

In tangible ways, therefore, we who partake of the Eucharist – the body and blood of Christ – must constantly proclaim and re-proclaim, preach and re-preach the cross, so that we may be reminded and be more willing – even against our will – to embody the cruciform love that the cross represents.

In this regard, Sieger Köder’s piece on The Last Supper brings out the Pauline message to perfection. Traced on the table-cloth beneath the bread-broken-to-be-shared spread on the table of the Lord is the shadow of a cross. Might we not hear Paul, the Apostle of the Crucified Lord, say to us: “Don’t you dare forget that the only reason we have this feast to celebrate is thanks to the fact that Someone died for us on the cross. And that Someone is the Lord Jesus Christ, crucified and risen!”

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, August 2013. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.