And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient unto death, even death on a cross. Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name which is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father. [Philippians 2:8-11]

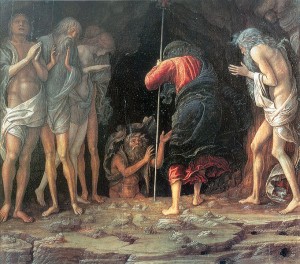

[L] Christ Descended into Limbo, by Andrea Mantegna, 1648. [M] Duccio Di Buoninsegna’s Descent to Hell, 1308-11. [R] Harrowing of Hades, fresco in the parecclesion of the Chora Church, Istanbul, c.1315.

Again, again and again, a seemingly endless string of friends and strangers have raised an emphatic question with us and made an adamant statement to us.

The emphatic but rhetorical question is:

- “Why does the new translation of the Apostles’ Creed have to say Jesus descended to hell?”

It is rhetorical because the enquirers needed no explanation, for the adamant and quite contemptuous statement that always followed the question is:

- “I will never – repeat never! – say it during Mass.”

What is that all about?

Catholics have been used to professing in the Apostles’ Creed that Jesus, after his suffering and death, “descended to the dead” and, as they emphatically say to us each time, “repeat not to hell.”

Asked why they are so emphatic about it, their response is adamant: “Jesus, without sin, could not descend to hell. Hell is for sinners who have no chance whatsoever of ever coming out.” On and on, they would continue, in basically the same non-negotiable vein.

What is the problem here, do you think?

We suggest that the first problem does not really lie with those enquirers, but with an inconspicuous shift over time in people’s comprehension of the term “hell” – a shift which these enquirers are not really aware.

1. Understanding “the abode of the dead” and “hell”

In paragraph 633 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church [CCC], we have an accurate and precise entry:

- Scripture calls the abode of the dead, to which the dead Christ went down, “hell” – Sheol in Hebrew or Hades in Greek – because those who are there are deprived of the vision of God.

The inconspicuous semantic “shift” we referred to has to do with the past equation of “the abode of the dead” with “hell”, that has gradually been diluted and then separated. Today, the two are no longer understood by many – our enquirers included – as representing the same “locale”. Indeed, for these people, the two terms are clearly distinguished and represent two starkly different and sharply contrasting locations.

In studying this question, it is best we turn to the Bible to see what it teaches about the realm of the dead. In the Hebrew Scriptures, the word used to describe the realm of the dead is sheol. It simply means the “place of departed souls.” The New Testament Greek word for the place of the dead is “hades.” The English translation for both sheol and hades is hell. And so, in Scriptures, hell simply meant the abode of the dead without distinction. The New Testament further indicates that hades is a temporary place, where souls are kept as they await the final resurrection and judgment.

The next part is crucial. This realm of the dead – that is to say, sheol in Hebrew or hades in Greek or hell in English – is a realm with two divisions, the abodes of [a] the saved and [b] the lost. (Some references for the term hades may be found in Matthew 11:23, 16:18; Luke 10:15, 16:23; Acts 2:27-31.)

- From the parable of Lazarus and the rich man in Luke 16, we learn that the abodes of the saved and the lost are separated by a “great chasm” (Luke 16:26).

- The abode of the saved was called “paradise” and “Abraham’s bosom.” When Jesus ascended to heaven, he took the occupants of paradise (believers) with Him (Ephesians 4:8-10).

- The abode of the lost is called “Gehanna” and there are lots of references for this in the New Testament. You will need to refer to the Greek New Testament to pick out this word, for most of the English Bibles just simply translate it as “hell” as they do for “hades”, which is not very helpful for a closer analysis. If you are interested, you can check out Matthew 5:22; 5:29; 5:30; 10:28; 18:9; 23:15; 23:33; Mark 9:43; 9:47; Luke 12:5; and James 3:6. Just for the fun of it, recall Matthew 10:28 – “And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul; rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell.” This translation in the Revised Standard Edition adds a footnote on the translation “hell” that says “Greek Gehenna”. Or, recall Mark 9:47 – “And if your eye causes you to sin, pluck it out; it is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than with two eyes to be thrown into hell,” where the word “hell” is translated from the Greek word Gehenna. Or this citation from James 3:6 which is a perennial warning to us all – “And the tongue is a fire. The tongue is an unrighteous world among our members, staining the whole body, setting on fire the cycle of nature, and set on fire by hell” where, again “hell” is used for “Gehenna”.

- Did Jesus go to the paradise division of sheol/hades? Yes, according to Ephesians 4:8-10 and 1 Peter 3:18-20. Even more dramatically, recall Jesus saying to the “good” criminal hanging on the cross beside him, “And he said to him, ‘Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise’”[Luke 23:43]. But did Jesus go to Gehenna? No, he did not.

And so, in Catholic understanding, hell, as the abode of the dead, is a realm that has different areas for different categories of souls.

We might itemize this Catholic understanding in ten points.

- First, the souls of all the dead, whether righteous or evil, leave their bodies upon death and go to the abode of the dead, which is hell, while they await the Redeemer. The abode of the dead is “hell” because it is a place deprived of the vision of God.

- Second, however, because of the lives people lived while on earth and the things they did or failed to do while they were alive, not all souls are identical in virtues and righteousness.

- Third, CCC#632 explains that the many scriptural testimonies of Jesus being “raised from the dead” presuppose that the crucified one sojourned in the realm of the dead prior to his resurrection [see Acts 3:15; Rom 8:11; 1 Cor15:20; cf. Heb 13:20.] We are to grasp this as the first meaning given in the apostolic preaching to Christ’s descent into hell: that Jesus, in solidarity with all of humanity on account of his incarnation, experienced death and in his soul joined the others in the realm of the dead, which is hell.

- Fourth, by the expression “He descended into hell”, the Apostles’ Creed confesses that “Jesus did really die and through his death for us conquered death and the devil ‘who was the power of death’” [Hebrew 2:14] (CCC#636].

- Fifth, however, it is important to also know that it is in “his human soul united to his divine person” that Jesus went to the realm of the dead (CCC#637).

- Sixth, so Christians understand that Jesus descended into hell, the abode of the dead, not as another human soul, but as Savior, proclaiming the Good News to the souls imprisoned there.

- Seven, since not all the souls imprisoned in the abode of the dead are the same, they are kept separately in different divisions of hell. In Luke 16:22-26, Jesus tells the parable of the poor man Lazarus who was received into “Abraham’s bosom”, whereas the rich man in that parable was deprived of that reception. In hades [hell, abode of the dead], he was in an area “far off” from where Lazarus was, the two being separated by “a great chasm”. While the rich man suffered torment and was in anguish, the poor man received comfort at the bosom of Abraham.

- Eighth, while, therefore, both the rich and poor man’s souls were in hell, the abode of the dead, the rich man was in a section known as “Gehenna”, a place where damned souls go after death.

- Ninth, the other souls, known as holy souls await their Savior in Abraham’s bosom. They, like the poor man and the good thief nailed to the cross next to Jesus, were in a section known as paradise.

- Tenth, Christ went down to hell to open heaven’s gates for those just souls in paradise who had gone before him (CCC#637).

2. Catholic understanding of where and why Jesus went on Holy Saturday

What happened on Holy Saturday? Where did Jesus go?

CCC 631, quoting Ephesians 4:9-10, says:

- Jesus “descended into the lower parts of the earth. He who descended is he who also ascended far above all the heavens.” The Apostles’ Creed confesses in the same article Christ’s descent into hell and his Resurrection from the dead on the third day, because in his Passover it was precisely out of the depths of death that he made life spring forth.

On Holy Saturday, therefore, Jesus descended into hell, the abode of the dead. He delivered the souls of those who awaited him in Abraham’s bosom and opened heaven’s gate to those just souls [CCC#635]. Citing ancient councils and medieval theologians, the Catechism states further:

- Jesus did not descend into hell to deliver the damned, nor to destroy the hell of damnation, but to free the just who had gone before him.

Citing the First Petrine epistle, CCC#634 states categorically that “The gospel was preached even to the dead” [1 Peter 4:6]. Thus, the Catechism teaches:

- The descent into hell brings the Gospel message of salvation to complete fulfilment. This is the last phase of Jesus’ messianic mission, a phase which is condensed in time but vast in its real significance: the spread of Christ’s redemptive work to all men of all times and all places, for all who are saved have been made sharers in the redemption.

In the next paragraph, CCC#635, the Catechism follows through with this idea, and explains that “Christ went down into the depths of death so that ‘the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God, and those who hear will live’” [see John 5:25; cf. Matthew 12:40; Romans 10:7; Ephesians 4:9]. Further explanation details the fruits of Jesus’ sojourn to the abode of the dead:

- “the Author of life”, by dying destroyed “him who has the power of death, that is, the devil, and [delivered] all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong bondage” [see Hebrews 2:14-15; cf. Acts 3:15].

- Henceforth the risen Christ holds “the keys of Death and Hades”, so that “at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth” [see Revelation 1:18; Philemon 2:10].

3. Harrowing of Hades in the Eastern Tradition

In Harrowing of Hades, raising Adam and Eve is always depicted in the East as part of the Resurrection icon, and is a great deal more common and prominent in Orthodox iconography compared to the Western tradition. It is the traditional icon for Holy Saturday and is used during the Paschal season and on Sundays throughout the year.

This traditional Eastern Orthodox icon does not depict simply the physical act of Jesus’ coming out of the tomb, but rather it depicts what Orthodox Christians believe to be the spiritual reality of what his death and resurrection accomplished.

The white and gold vestment of Jesus symbolizes his divine majesty. His posture on the brazen gates of Hades (also called the “Doors of Death”) symbolise the breaking of the door on account of his cross. The message is, by his death on the cross, Jesus trampled down death. His left and right hands each grabs hold of Adam and Eve, pulling them up out of Hades. Traditionally, he is not shown holding them by the hands, but by their wrists, to illustrate the theological teaching that mankind could not pull itself out of its ancestral sin; rather, salvation depended entirely on the work of God. Surrounding Jesus, we see various righteous figures from the Old Testament, and they include Abraham, David and so on. At the bottom of the icon, we can see Hades depicted as a chasm of darkness. Often in these icons, one or two figures are shown in the darkness, bound in chains, who are generally identified as personifications of the Devil or Death.

4. A follow-up question

Once people have listened attentively to your explanation that “hell” is the same as “the abode of the dead”, that Jesus descended to the “paradise” side of “hell”, and that he opened the gates of heaven to those just souls kept temporarily in paradise, you are likely to get an immediate follow-up question. That question is along the line of: “If saved souls are already lifted to heaven, and lost souls are kept in Gehenna, why do we still need the Last Judgment?”

For our answer, we need to imagine a three-part play:

- 1. Upon death, the soul separates from the body and goes to the abode of the dead.

- 2. There is “life after death”: good soul goes to paradise to await lifting to heaven by Christ; bad soul goes to Gehenna.

- 3. There is “life after life-after-death” [- a famous expression by Bible scholar N.T. Wright]: this is the time of the Last Judgment, the time of the resurrection of the body, when body is reunited with the soul. We find St Paul’s famous arguments for the truth of the resurrection of the body in 1 Corinthians 15.

5. What does it all mean for us?

We return to where we started. Would you now say “He descended to hell” during Mass or in private prayers? From where we stand, so long as we know what it is that we are praying, and that we are praying with the Church in meaning and substance, the question of semantics does not seem all that important any more.

More important, perhaps, is when we face the question “What happens to me when I die?” There, Scripture as the authoritative Word from God draws us to the caveat that we shall not take our eyes off Jesus of Nazareth. In order to know what will happen to us after death, we must look carefully at what Scripture reveals about the paschal mystery of Jesus. This basic connection between the fate of Jesus and the fate of the Christian is of critical importance. Not only does it act as a timely corrective to those currents of contemporary thought that are overly apophatic (that is, “we do not know”) about personal eschatology, it positively asserts that we are by no means left in complete darkness. Furthermore, there is absolutely no need for us to depend primarily on those anecdotal evidence of so-called “near-death experiences” or to some private mystical experiences for answers to questions about what lies beyond the grave.

The message from the Bible is: keep the faith, fight the long fight, stay virtuous and upright, stay the course no matter what. In his death, Jesus went down to the abode of the dead to lift up just souls to heaven. In raising Jesus from the dead, God affirmed Jesus and all that he stood for. Christians contemplating “the end” must stay focused on Jesus Christ and his earthly sojourn. An authentic Christian eschatology cannot but be a Christological eschatology. So a robust Christian vision of “the end” looks first and foremost to Jesus Christ whose Passover “from death to life” (John 5:24) reveals the truth about the fate of the Church as a whole and the individual Christian in particular. Like Jesus, therefore, we can expect the descent of our living-but-disembodied soul to the realm of the dead, and our final resurrection to bodily but unending life, and this bodily ascension into the heavenly realm where we shall be face to face with the glory of the Trinity. God is faithful. He did it for Jesus. He will do it for us, provided we live the faith.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh. July 2013. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.