21 For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you should follow in his steps.

22 “He committed no sin, and no deceit was found in his mouth.”

23 When he was abused, he did not return abuse; when he suffered, he did not threaten; but he entrusted himself to the one who judges justly.

24 He himself bore our sins in his body on the cross, so that, free from sins, we might live for righteousness; by his wounds you have been healed. [1 Peter 2:21-24, NRSV]

The Crucifixion, by Tintoretto, 1565.

The Crucifixion, by Tintoretto, 1565.

On the question of how salvation is achieved through the cross of Christ, a short chapter 3 in the biography by Sergio Rubin and Francesca Ambrogetti titled Pope Francis: Conversation with Jorge Bergoglio offers some tantalizing pointers for reflection.

First, they lay the foundation for the chapter by addressing the first medical crisis of the twenty-one year old Bergoglio as he struggled with a severe bout of pneumonia. The delayed diagnosis necessitated an “excision of the upper part of his right lung.” Though the surgery was successful, convalescing was “enormously painful”.

Living with a “pulmonary deficiency” ever since, Bergoglio says he has learned to discern the “important” from the “trivial” in life, and to live with human limitation.

Second, cutting through visitors’ unhelpful clichés and platitudes, Bergoglio reveals that while convalescing, he found real consolation and peace only in what Sister Doloros said to him: “You are imitating Christ.”

In so saying, Sister Doloros has introduced an excellent lesson for Christians as they seek to confront pain. Can pain be a “blessing” if it is endured in a “Christian” manner? This is how Bergoglio sees it:

- “Pain is not a virtue in itself, but you can be virtuous in the way you bear it. Our life’s vocation is fulfillment and happiness, and pain is a limitation in our search. Therefore one fully understands the meaning of pain through the pain of God made Christ.”

- “The key is to understand the cross as the seed of resurrection. Any attempt to cope with pain will bring partial results, if it is not based in transcendence (i.e., an existence or experience beyond the normal, physical level). It is a gift to understand and fully live through pain. Even more: to live life fuflfilled is a gift.”

- It is true that at times, suffering has been overemphasized. In this, the Church is sometimes guilty of focusing too much on pain as the path to getting close to God and too little on the joy of resurrection. The film Barbette’s Feast is excellent in exposing a tendency to take prohibitive limits to the extreme. Living an exaggerated puritan Calvinism, the characters in the film equated the redemption of Christ with a negation of the things of this world. When an abundant meal brought forth the novelty of freedom, they were all transformed. Until now, they had not known what happiness was. They feared love, devoted themselves to the gray side of life, and lived their lives crushed by pain.

- Depending on particular era of the Church and the culture in which the Church found itself, it is true that suffering had been exulted. The Catholic Church could give the erroneous impression that the main symbol of the Christian faith is “a crucified Christ dripping with blood.”

In the study of Christology, particularly in regards to how Christ effected salvation for humankind through his death on the cross, there is a somewhat shocking obduracy on the part of many Christians who embrace a theory that carries a mixture of some or all of the following elements:

- that it was God’s will that His Son must die in atonement for human sins,

- that the Father sent the Son to die,

- that Christ died a horribly painful and humiliating death on the cross in satisfaction of the penalty owed by humanity to God on account of sin,

- that Christ suffered and died in substitution for sinful humanity who were and are incapable of rendering satisfaction for the deserved penalty,

- that in wrath, God had turned His face away from sinful humanity,

- that His anger now appeased by Christ-the-Son paying the ransom dying a painful death on the cross, God then turned His face back to humanity so they can once again approach God…

Traced to medieval theology, this way of understanding salvation by Christ’s death on the cross is essentially suggesting that God cures the violence in human sins by authorizing another violence, namely, having His Son killed on the cross. This is an immensely cruel and violent understanding. It is cruel to God for insinuating:

- that God is full of wrath, mean and vengeful,

- that God is violent,

- that God is a sadist who enjoys cruelty, blood, pain, and human humiliation, and even wills these things,

- that God is a worse character than even sinful human parents who themselves cannot possibly “willed” the death of their own children,

- that God is a divinity without love, mercy, compassion and forgiveness…

All this, and more, is a reflection of the violence in human hearts projected onto God as we continue to subscribe to one or the other variation of a medieval atonement theory.

Now back to the biography on Bergoglio, where two hints have profound implications.

First, instead of the negativities associated with quite a natural rejection of pain and suffering, Pope Francis spoke of serenity. “Violence” is not overcome by violence, but by a peaceful, interior strength rooted in a spiritual imitation of Christ. When “violence” otherwise associated with struggles, sufferings and pain is replaced by “peace”, what we have is a profound reality of existential salvation. Christ, then, did not magically “save” Bergoglio by a violent and bloody death on the cross. Rather, by his steadfast non-violent attitude in the face of meaningless human violence, torture and pain, Christ died to set humanity a serene and non-violent example. He went all the way to Calvary, not because the Father demanded a bloody death from His Son, but so that Christ can show humanity that he loves all the way, till death, to show the world that the evangelical values of which he taught in words, can be achieved in reality. The phrase “imitation of Christ” bespeaks, then, in the first place, of Christ setting an example – “Do this in memory of me”. Neither do we have to insult God through reliance on some medieval theology which in the last analysis yields an image of God that is wrathful, vengeful and sadistic, nor do we need to suggest that Christ by his violent death on the cross has completely achieved our salvation, leaving nothing for sinful humanity to do. The stories of Jesus of Nazareth in the four Gospels is unified in an overarching theme for all Christians: the “Imitation of Christ” remains the singular discipline for all who would follow him.

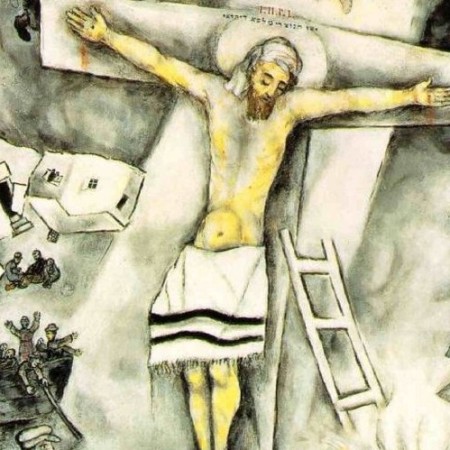

Second, our reflection here is anything but a rejection of the cross of Christ. On the contrary, the whole idea here is how Jesus approached his cross. As Jesus embraced his cross serenely, so too are we called to do likewise in our myriad “crosses” life dishes out to each one of us. Again, Pope Francis is very helpful here. He points out that the exultation of suffering in the Church depends a great deal on the era and the culture. Martyrdom, often highlighted by the Church as a path to sainthood, must be properly understood. It should not be associated with the gruesome; rather, a martyr is one whose life is a testimony of faith and trust in God. It is, seriously, giving one’s life to faith. “Christian life is bearing witness with cheerfulness,” he says, in imitation of the way of Christ. That is why Pope Francis finds Marc Chagall’s “White Crucifixion” a painting of exquisite beauty. A Jewish believer, Chagall has presented Jesus’ approach to the cross not as something cruel, but as something hopeful.

Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion, 1938.

Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion, 1938.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, May 2017. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.