23 When the soldiers had crucified Jesus, they took his clothes and divided them into four parts, one for each soldier. They also took his tunic; now the tunic was seamless, woven in one piece from the top. 24 So they said to one another, “Let us not tear it, but cast lots for it to see who will get it.” This was to fulfill what the scripture says, “They divided my clothes among themselves, and for my clothing they cast lots.” 25 And that is what the soldiers did. [John 19:23-25, NRSV]

The Crucifixion, by Andrea Montagna c.1459.

The Crucifixion, by Andrea Montagna c.1459.

In a superbly composed and very detailed painting on The Crucifixion, Andrew Montagna paints realistically with his severe and sculptural style. The setting of the Crucifixion is a rocky plateau outside the walled city of Jerusalem in the background. He offers generations of Christians marvelous opportunities to meditate on the wiles of individualism versus the power of solidarity at the death of Jesus of Nazareth.

With Christ at the centre of the painting to emphasise the magnitude of the Saviour’s sacrifice, viewers are invited to reflect on what drives Jesus’ free acceptance of his death. The noble act of ultimate sacrifice made by Jesus is to make possible the salvation of sinners of the world. This sacrifice speaks of what selflessness, love and mercy really are. But, how do human individuals respond to Jesus’ sacrifice? Montagna offers some hints in this masterpiece.

First, he seems to invest a great deal on the two figures that stand in front of the three crucifixions, one on the right and one on the left, by presenting a picture of amazing faith in both of them. One might connect this with John’s narrative gospel account where he captures Jesus saying, “And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all men to myself” (John 12:32). On the right of the three crucifixions stands Saint John, “the disciple whom Jesus loved”, who followed Jesus all the way along the via dolorosa and remained at the foot of the cross throughout. John the Beloved on the right is balanced on the left by a mounted soldier whom, with his better-decorated armour, reminds us of the centurion of Mark 15:39. Despite being a pagan, this centurion could profess a shocking pre-Resurrection faith at the foot of the cross:

- And when the centurion, who stood facing him, saw that he thus breathed his last, he said, “Truly this man was the Son of God!” [Mark 15:39]

The evangelist Mark, it seems, wants to stress not only that it is possible to have faith before and even without the resurrection, however incomplete that faith may be, but that, more importantly, a three-day-theology singularly focused on Good Friday, Holy Saturday and Resurrection Sunday is grossly inadequate without taking into account of the entire life and ministry of Jesus of Nazareth before the Holy Week.

Second, while the three crosses are balanced, the unequal lighting places the unrepentant thief on Jesus’ left in the shadows, thus signifying the “darkness” even at the very end of his life. Christ’s head and body, however, leans towards the penitent thief on his right, who is displayed in the light, thus pointing to a glorious prospect at his life’s end.

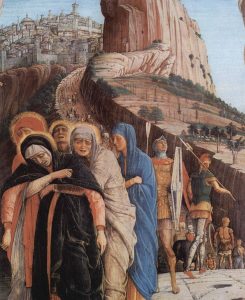

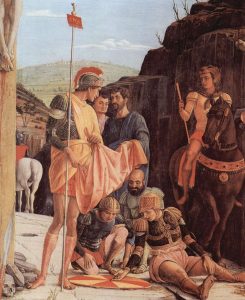

Third, behind the three crosses, Montagna lets the story unfold in two sharply contrasting scenes at the foot of the cross, where a group of women on one side (with Mary, the mother, prominent in the center) balances a group of soldiers on the other. The scene on the left of the panting shows these soldiers casting lots as they vied for Jesus’ tunic, while the scene on the right shows the group of grieving women hustled together in mutual support and to care for Jesus’ mother, Mary. This, it would seem, is very telling of the human hearts underneath or, in this case, real human attitudes “behind” the cross of Jesus Christ.

- Not only are the Roman soldiers portrayed as generally nonchalant and distracted from the grisly torture they are inflicting, they are even gathered together to cast lots to vie for the spoils, in this case, Jesus’ outer coat. They display the dark side of the fallen human nature, self-centered, grabbing for personal gains, oblivious even to the atrocities they do to others, and the dire human suffering around them.

- By contrast, the group of grieving women are hurdled together in mutual support and, crucially, in spiritual solidarity with the Crucified One. Superficially religious people, Dietrich Bonhoeffer once wrote, practise religion by looking to the God of power but, he insisted, genuinely religious people stay by God in times of God’s powerlessness and weakness, when there are no more favours or handouts, healings or miracles, when Christ the Son is crucified to a humiliating death on the cross. This is the Christ who said that when we fail to come to the aid of the powerless and the weak, the Poor and the needy, we fail to help him in times of need (Matthew 25:31-46).

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, March 2020. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.