18 Then one of them, whose name was Cleopas, answered him, “Are you the only stranger in Jerusalem who does not know the things that have taken place there in these days?” 19 He asked them, “What things?” They replied, “The things about Jesus of Nazareth, who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, 20 and how our chief priests and leaders handed him over to be condemned to death and crucified him. 21 But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel. [Luke 24:18-21, NRSV]

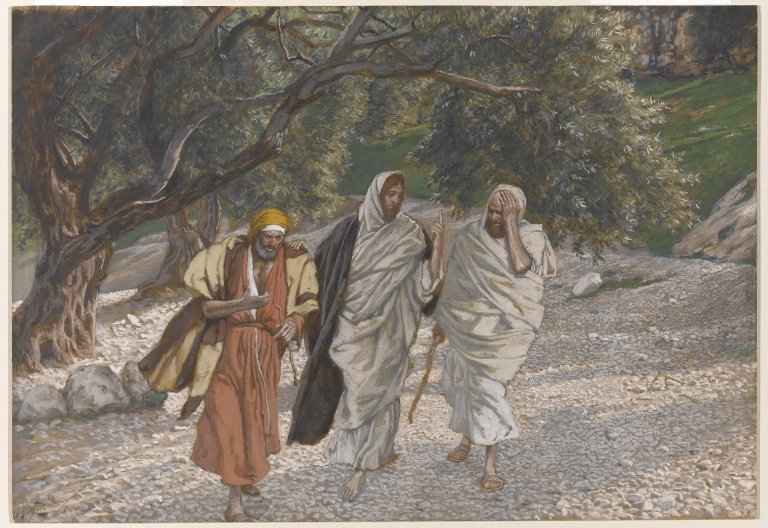

The Pilgrims of Emmaus on the Road, by James Tissot.

The Pilgrims of Emmaus on the Road, by James Tissot.

It is in the afternoon of the first Easter day, when the two disciples leave Jerusalem to return to Emmaus. After a morning full of strange reports, they still do not have a clue what was going on. On the way, they are joined by a mysterious stranger who engages them in conversation about those events. The central point of the story comes up real quickly once the stranger asks them what it was that they were talking and discussing. Upon that question, the two at once begins to verbalise their cherished “hope”.

In ministry, we are ever conscious of the power and the lingering pain behind the three words “we were hoping”.

“We were hoping…”

“Hopes” and “expectations” can be quite synonymous words, like when your expectations mean your strong hopes or beliefs that something will happen or that you will get something that you want. So sometimes when we hear people say, “I expect the Yellow Team will win the competition,” we know what their hopes are. The expectations in a project are what we hope to achieve. They are the goals.

On the other hand, “hopes” and “expectations” can take on rather different loads of meaning as well. For instance, emergency ward medical staff in a busy city bustling with night life work long and hard most nights. Rarely is a night so quiet that they can sleep enough to feel like a fresh human being the next day. But every once in a while, there is no fires to put out, the phone is quiet, and they do not work all night. They all hope for such a night, knowing how rare this occurs. So they develop a saying: “Expect the worst, hope for the best.” The problem is, anytime the staff expect a quiet night but do not get it, the work becomes that much more painful, and the night that much longer than usual. The problem in this case is not the actual work. It is the intrusion of a psychological disturbance. Of all the difficulties to overcome, psychological obstacles arising from unmet expectations are the hardest.

Back to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, when they say, “We were hoping that he was the one who would redeem Israel,” we can at once sense that this is a hope that has a rich history. How did their hope come about? Where were they coming from? What was their (or Israel’s) problem? The more we are conscious of the history of the Jewish people, the better we can understand what is in the hearts and minds of the two disciples as they converse with the stranger.

Early in this Emmaus episode then, Luke is already suggesting to the readers to be conscious of Israel’s history and the hopes and expectations of the Jewish people in ancient Palestine at the time of Jesus. Clearly, they had been living out of a powerful narrative that controlled their lives. It narrates a story that had a long history, one that was filled with prophetic promises – promises made by Yahweh for which the Israelites have a long tradition of praising in psalms. The backdrop to it all was of course the exodus, their defining story of God’s mighty hands liberating their ancestors from slavery in Egypt, those ancestors’ sojourn in the wilderness for forty years, and their final entry into the promised land of milk and honey. Thereafter, the same thread connected successive narratives in which God repeatedly delivered His Chosen People from various foreign powers and pagan oppression. Whenever the Israelites found themselves in hard times under foreign rules, you hear the psalmist called out: let not the spirit be cast down within you. Hope in the Lord, for He is our help and our God. Praise Him!

Under the oppressive rules of the Roman occupiers, Jews in the first century had every reason to believe that the exile was not completely over, for God’s great promises through the prophets had yet to become reality. In other words, Israel would still need to be “redeemed”, a word that carried serious overtones of the exodus. As the exodus witnessed to the great historical moment of God’s covenant-making with His people, what they now needed was covenant renewal. Their old Scriptures were awaiting a suitable ending, and many followers of Jesus had built up this hope and expectation – “we were hoping” (which of course meant “we were expecting”) – that the ending would materialize in Jesus. So great was the hope and expectation that now that Jesus had been crucified, all hopes were dashed. That loss of hope was a shocking experience all the more because Jesus the mighty one of God was so thoroughly humiliated and violently killed. Given that background, one must not judge the two disciples negatively in any way, such as thinking badly of them for not at all feeling guilty for leaving town, for seemingly abandoning Jesus’ cause so easily.

Actually, far from being a simple statement of reflection, what the two disciples are doing is to hark back to a plea for vindication as in Psalm 43:

- “Vindicate me, O God, defend my cause against the ungodly people! Deliver me from the deceitful and unjust! Send out your light and your truth; let them lead me! Why are you so heavy, O my soul; hope in God!”

So the plea in Psalm is a heavily loaded plea that also subscribes to the Israelites’ traditional messianic and prophetic movements. Accompanying those movements were some clear outlines of the Jewish spirit such as holiness, zeal for God and the law, and military revolt, among others. With God on their side, they would defeat the pagan hordes. This was how Scriptures outlined the climactic event, when Israel would become King of all the world.

But now, Jesus their expected liberator was crucified. Crucifixions had marked the common end of many would be liberators of Israel before Jesus came on the scene. On the lips of the two disciples, it is indeed a loaded “we were hoping…” they utter to the stranger. It is loaded with lamentations as the crucifixion of Jesus is the complete and final devastation of their hopes and expectations of the grand and final liberation of Israel.

What upset the disciples the most was not so much that they remembered from Deuteronomy that a crucified person was under God’s curse (Deuteronomy 21:22-23). Nor was it just a matter of them not having by that time worked out a theology of Jesus’ atoning death. Rather, for the followers of Jesus at the time, the very death of Jesus by Roman crucifixion already carried some deeply troubling theological and political implications. In the words of Biblical scholar, N.T. Wright, the crucifixion meant that

- the exile was still continuing,

- that God had not yet forgiven Israel’s sins,

- that the pagans were still running the world, and

- that their thirst for redemption, for God’s light and truth to come and lead them, was still not satisfied.

With the words “We were hoping…”, therefore, Luke places the readers at the most basic level of chapter 24 of the Gospel, a level that defines the vigour with which the two on the road are “talking and discussing together”. Just a few days ago, they were travelling up the road in the other direction, towards Jerusalem, with big expectations that freedom for them and the whole of Israel was close at hand. But it turned out otherwise. Their laments are audible, as they explain to the stranger how the positive signs were all there: a prophet mighty in words and deeds was this Jesus of Nazareth; the mighty God was clearly with him, and his popularity testified to the people’s approval and acceptance. But now his utter rejection by the religious leaders, and death in the hands of the foreign power, utterly confused them as to how they could be so wrong.

Worse still, they are further confounded in their confusion in that just this very morning they heard reports that some women in their group of Jesus’ disciples had been to the tomb and seen a vision of angels who told them that Jesus was alive. What was that all about? More than anything else, it was really unwanted disturbance that had nothing to do with the matter of their concern – their hope for the liberation of Israel. Or so they thought. In any case, it was certainly unexpected disturbance to an already difficult time of sorrow and disappointment over hopes dashed.

One thing must be clear: the two disciples’ hope betrays a certain storyline that dominates their existence. They are ripe for the shock of their lives in a “different” narrative. There is going to be the pain of surrender of their precious storyline as the stranger takes over and tells the story differently. They will be told that they have been blind to the prophetic promises and the psalmists’ prayers. They will learn what it means to be God’s Messiah to a world of sin, violence and inauthentic worship. They will be shocked to learn that their entire perspective on the message of the old Scriptures will need to be overhauled, as Jesus the crucified but risen stranger explains God’s very Word to them. And as the stranger breaks open the true meaning of the ancient texts to them, giving them a wholly different take on how the revelation of the Messiah was actually prophesied, their hearts will burn within them [Luke 24:32]. Their eyes will be opened with new faith to “see” the crucified and Risen Lord, their life will be transformed once they transit from blindness to faith, and they will know and be blessed with the memory and thus the presence of the resurrected Christ amongst them.

Right now, however, at the beginning of their home-bound journey to Emmaus, the two disciples are despondent. Their foolishness, slowness of heart, or lack of belief in the prophets – none of that was a matter of pure spiritual blindness. It was a matter of telling and living the wrong story. This is not the time for Jesus to reveal himself to them yet. First, they need to be re-catechised with the right and complete story in their head as well as in their heart, before they could truly recognize the risen Lord. To lift their despondency, their minds need a new vision so their hearts may again be burning with zeal for God’s mission. The new vision shall see:

- That the cross was God’s means of defeating evil once and for all;

- That pain and suffering had always been and will always be part of the path;

- That this was how the exile would finally end;

- That sins were to be forgiven;

- That this was how God’s light and truth looked like;

- That this was how the wayward people of God would be led back into God’s presence.

Giving up what we treasure, submitting to God – from this Christians easily glide over to the idea of carrying the cross daily. Much of the times, people keep their sorrows to themselves. In The Corporal & Spiritual Work of Mercy: Living Christian Love and Compassion, Mitch Finley points to the sorrow with which many parents live because of choices their grown children have made. Most parents carry sorrows in their hearts, sorrows they keep to themselves in the most part, of their children failing to live up to their expectations. We each have our crosses to bear. Life is sometimes a “vale of tears”, and every life brings with it “crosses.” Living a Christian life includes a response to this dark side of life too. This connects well with the Catholic experience. As William Bausch puts it: “We are all on a journey. Our paths are uneven. Losses, at times, are heavy. We seem to be marching with no purpose while searching for some meaning to our lives and our deaths. We need the breaking of the bread at Mass, to be assured that Jesus has not left us alone. The Risen Christ, present in a unique way in the communal Eucharistic celebration, reminds us that one day, we too, shall shine bright and beautiful with the fullness of his love.”

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, March 2021. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.