25 Then he said to them, “Oh, how foolish you are, and how slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have declared! 26 Was it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things and then enter into his glory?” 27 Then beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them the things about himself in all the scriptures. [Luke 24:25-27, NRSV]

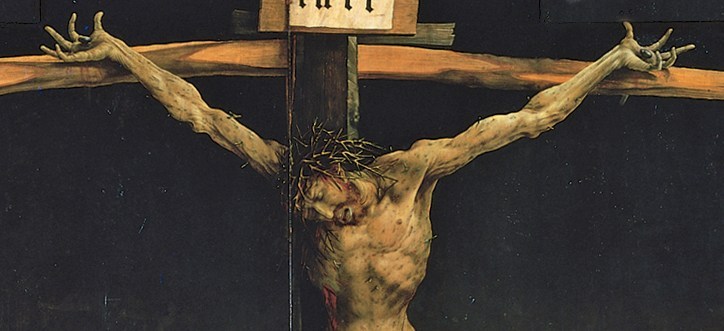

Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grunewald, c. 1515, (details).

Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grunewald, c. 1515, (details).

The Romans ran a system of torture aimed at sending a chilling message to all who would not heed the might of the Empire. Apart from inflicting the greatest pain, the cruelty of the Roman crucifixion was designed to humiliate and render the condemned as vulnerable as possible, to make the slow death a spectacle, and to create an ultimate deterrence. Why did the powerful Messiah (Saviour, Christ) have to suffer and die like that for our salvation? Deeply embedded in the Emmaus story is the difficulty early disciples had in accepting that Jesus, who was put through the Roman torture system, could have risen and was truly their Saviour.

Christianity understands Christ’s suffering death as atonement for human sin. “Atonement” brings together two related concepts. First, like Adam, sinning human beings separate themselves from the wishes of God and estrange themselves from His vision. Like Adam in Genesis 3 and the Prodigal Son in Luke 15, sinning humanity cut itself off from the original good relationship with God, banished itself from His presence, and fell away from grace. Second, “at-one-ment” is the bringing of wayward human beings back into good relationship with God, to be reconciled (“at-one”) again with the Source of life.

The dominant model in Western Christianity for understanding how this atonement works is the debt-repayment model. Humanity sinned against God. This sin-debt to God was beyond sinful humanity’s capacity to pay. As humanity could not redeem itself, it became death-bound and would die forever estranged from God. The incarnation of the Son of God became necessary so that the sinless Son of God could pay the sin-debt on behalf of humanity. Redemption became the inner motive of the Incarnation.

The most prominent representation of this Western model of salvation is Anselm’s satisfaction theory of redemption. In Anselm’s 1098 classic treatment, only the death of Jesus Christ the Son of God could be a sufficient vicarious satisfaction for the sins of the world. That “satisfaction” of sin-repayment for human sins by humans was possible on two counts: worthiness and sufficiency. First, only untainted or sinless payments were worthy and Jesus was truly sinless in his human nature. Second, Jesus’ sin-repayment on behalf of sinful humanity was sufficient because his human nature was wedded in its hypostatic union to the Second Person of the Trinity. This theory of redemption wrought on the cross, has served Western Christianity for centuries. Important elements of Anselm’s thoughts continue to rule theological arguments in this area even in contemporary times, waning a little only with cultural sensitivities to some issues arising from some parts of his theory.

Today, whether they are conscious of it or not, Christians do implicitly subscribe to some form of “satisfaction” theory: somehow, through Christ’s suffering and death, we are saved from eternal hell-fire; he paid the price, the “ransom” for our souls. For centuries, beneath this simple equation are a few “simple” assumptions, mostly grounded on “magical” views of baptism and salvation. Common is the assumption that salvation means upon the death of baptized Christians, their souls are destined for enjoyment in heavenly bliss (which of course implies that the non-baptised descend to torture in eternal hell-fire). Conveniently forgotten in all this, are human responsibility inherent in The Lord’s Prayer for God’s kingdom to be established “on earth as it is in heaven”, and our personal role in kingdom-advancement work within the discipline of Christian discipleship. Like the early disciples before they have had the experience of the Resurrection of the Lord and the descent of the Holy Spirit, we are attention-deficient to the Lord’s call to “take up your cross and follow me”.

Understandably, objections to different aspects of Anselm’s theory are many. Attracting the clearest disdain is his dependence on outdated honour-rule of the medieval feudal system and the legalistic debt-repayment-rule of the Latin juridical thinking. Even though Anselm never intended it, the negative image generated by his theory of a vindictive God eager for sin-debt repayment to appease His wrath, has drawn strong criticisms. This negative image of God is adamantly rebutted as being quite contrary to the God of love and mercy portrayed by Jesus in the Gospels. The next aspect to be shunned is the exclusive redemptive value placed on Jesus’ death, without taking into account the entire paschal mystery, let alone Jesus’ entire life and ministry. The fourth dissenting voice underscores the premise of physical suffering, imposed or freely accepted, on which the satisfaction theory erroneously presumes as sufficient to cancel out evil. Finally, the theory falls short for putting too much emphasis on sin and too little emphasis on love.

This being said, the significance of Jesus’ humanity in Anselm’s thoughts garnered much praise. Marking a shift in the history of Christian theology, Anselm insisted that God could not simply forgive human sins out of pure love, without involving humanity. Instead, sinning humanity must on its own freewill pay for its sins and return to God. Humanity must freely do it. Only in this way, Anselm reasoned, could God bind Himself to the order of justice – justice in punishment for wrongs committed – and at the same time respect human freedom, that is wrongdoers must learn to pay for their sins. From Anselm, then, Christianity got the “new” idea that contribution from the human nature of Jesus was indispensable for salvation. The divine nature of the Son of God was no longer the decisive factor. Salvation no longer turns directly on the divinity of Jesus, but on his true human nature. Humans have a crucial role to play. Cooperation from human free will is thus always necessary in the salvation of humankind – “take up your cross and follow me.” Jesus never said, “I have carried the cross for you, so you don’t have to.”

And so, to overcome the negative aspects of Anselm’s satisfaction theory, a clearer emphasis on Jesus’ constant alignment of his human will with God’s kingdom values is essential. This is a message of constant relevance in Christian discipleship, and one that takes on added significance in the season of Lent and the Holy Week. With heightened consciousness, the Church calls us back to serious meditation on what Jesus is all about. Throughout his ministry, Jesus was driven by an unrelenting desire to promote God’s vision for the world. He loved to the end. He calls humanity to embrace the values of God’s kingdom, bearing their crosses and bringing light to darkness in the world.

Salvation by a Reorientation of Human Freedom to God

The problem is that humanity has always been recalcitrant. Like a runaway freight train, humanity was heading for a crash. Its destiny was death-bound and it would die estranged from God, unless its sin-pattern was interrupted. For the love of humanity, Jesus took it as his mission to offer that interruption by freely sacrificing himself. That included a willing absorption of utter humiliation, torture and death. This could only be done in peace and non-violence, and he did. In doing so, Jesus shows that the exercise of human freedom, especially in situations of severe human suffering, always involves a struggle with the incomprehensible God. Reading from the Gospels, we can sense that Jesus’ suffering was compounded by the silence of God, despite his pleadings for relief (“Father, let this cup pass me by…”; “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me…”). All that he relied on was an utter faith and trust in a good God. Theology in this regard first teaches us that in his suffering, Jesus entered into solidarity with the suffering humanity. If you experience suffering in your life, go talk to the Lord. He has been there; he knows all about suffering. Theology then teaches that discipleship entails a struggle between taking only what is pleasant and good about being a Christian, and being conformed to Christ in a life that includes suffering and self-sacrifice. This ought to be clearest to us as we progress from Lent into the Holy Week.

- Jesus in the Gospels teaches us with clarity that new life and eternal life are possible only by the death of the self through suffering and service. Our covenant with God can never be complete unless we are willing to curtail our runaway “freedom” and align our will with Jesus’ path of suffering and dying for others. Self-sacrificing love is at the heart of the Christian religion. The only solution for all humankind is to learn to love. Because Christ went to his crucifixion in love and sacrifice for human salvation, his Cross becomes the symbol of hope for the world. As God raised the Crucified One from death, He vindicated Jesus, affirmed all that he taught and did and stood for, and exalted him for his suffering love.

From the mountain where he preached God’s kingdom-vision for the world (the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5-7), to the mount of Calvary, Jesus’ life and ministry, his “noble and beautiful human life” (borrowing a phrase from the Dutch New Catechism, 1969) in words and deeds, witness to an absolute obedience to God’s kingdom vision. For the first time in human history, Jesus’ life mission marks a definitive break and replacement of the prototypical Adamic sinning humanity. Jesus the Christ is the archetype of the true human.

St Thomas Aquinas affirmed that like all human acts, the human acts of Jesus bore consequences to his future. Good and evil have bearings too on our own future. Jesus chose to put the seal on constant self-renunciation as the absolute affirmation of the Father. This led him to preach and live God’s kingdom-values till death. Whenever Jesus’ life and death are proclaimed at communal gatherings, believers will be summoned to proclaim Jesus’ obedience and in turn profess their own commitment to self-dedication. We are to overcome the root of sin, to renounce egoism, for without self-renunciation, there can be no affirmation of the other. This is why salvation is best understood as freedom that comes through the Cross. Old Testament prophets looked forward to the Cross and the saints of the New Testament looked back to it for guidance.

The cross as an exercise of human freedom by Jesus is rightly underlined by Karl Rahner, SJ. God gives self-offering love to the world. We are made with the freedom to accept God’s love and to promote or neglect it in the world. The more we are open to God and the Gospel, the more human and free we become. Scriptures offer the vision of that irreversible point where the history of God’s self-offering meets with its free acceptance in the world. Jesus stood precisely at that point. Jesus lived a human life so authentic and acceptable to God that God accepts the world to a point where Rahner says He can no longer let it go. In Jesus then, God is pleased to receive “that gift of creaturely freedom in which this freedom of the world definitely accepts God’s offering of Godself.” This is the definitive contribution of Jesus the true man. He is the one person who, from the depth of his interiority, lived a human existence that signifies the definitive wishes of God to the world, and at the same time the assent of the world to this God. Jesus is the one who “surrenders every inner-worldly future in death,” and who is thereby “accepted by God finally and definitively” (Foundation of Christian Faith, 211). His complete surrender of life to God reached fulfillment which became historically tangible precisely in the resurrection. This individual, Jesus of Nazareth, has exemplary significance and is the “effective prototype” for the world as a whole. By his death and resurrection, Jesus has shown that the evangelical values of which he preached and lived, are humanly achievable. Disciples are empowered to do likewise. We do not have to see Jesus as “victim”. Instead, he died to give us the “heartbreaking empowerment” (Elizabeth A. Johnson, She Who Is, 159). In earthly terms, Jesus’ mission was a failure; so he had to fulfil it in God’s way – which led to the cross (Malcolm Muggeridge, Jesus Rediscovered, 81). Jesus on the cross witnesses to a true life for all where triumph comes through “failure” (John J. Navone, Triumph Through Failure). Calvary is not a catastrophe; the “darkness” of Jesus’ death happened on “Good Friday”. The prayerful suffering and death of Jesus transforms believers.

- As a grain of wheat must die so as to produce a harvest (Jn 12:24), we too must learn to die in little ways and in a gradual process. In every act of humility we die to pride. Acting in courage, we die to cowardice. In kindness, we die to cruelty. Turning to love, we die to selfishness. As we give, we receive. As we forgive, we are forgiven. As we put death to the false human self, our true self made in God’s image is born to eternal life.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, June 2021. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.