Part I: Sandwich composition and a soft landing

And Jesus said to the fig tree, “May no one eat fruit from you again” [Mark 11:14].

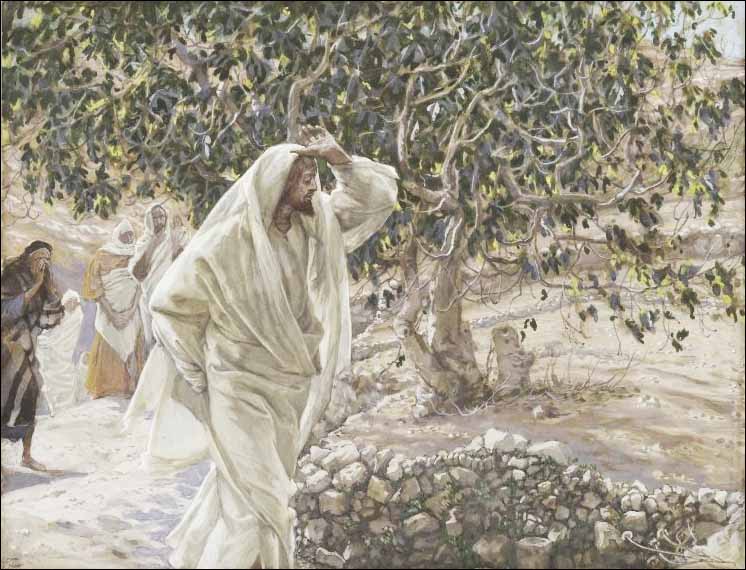

[L] Jesus Cursing a Fig Tree. James Tissot, c.1890. [R] The Purification of the Temple by Jacopo Bassano. [Note: An artist who shows cattle and sheep and a whip in Jesus’ hand is influenced by the Johannine narrative.]

This reflection gathers some of our thoughts in response to questions people have raised with us concerning the episode of Jesus cursing the fig tree in the Gospels. Their questions centre on what seems to them to be an incomprehensible action on the part of Jesus cursing a fig tree for not producing fruits out of season.

This reflection gathers some of our thoughts in response to questions people have raised with us concerning the episode of Jesus cursing the fig tree in the Gospels. Their questions centre on what seems to them to be an incomprehensible action on the part of Jesus cursing a fig tree for not producing fruits out of season.

In response to their questions, we propose a reply in two parts.

Part one proceeds from the smaller angle of St Mark’s sandwich composition in 11:12-26 and outlines an interpretation that leads to a “softer” landing.

Part two, in the next post, takes a second look at the fig-cursing and Temple-cleansing episodes from the larger angle of Jesus’ pilgrim journey from Galilee to Jerusalem – towards the Holy Week and the Cross. This second approach will, amongst other things, link up with Pope Benedict XVI’s latest book on Jesus of Nazareth [Part II] and offer an interpretation that takes us to a “harder” landing.

Only Mark and Matthew have the cursing of the fig tree, while all 4 Gospels have the cleansing of the Temple. Matthew 21, however, covers both stories in one day, while Mark 11 spreads them over 2 days! While the Synoptic Gospels place the Temple cleansing episode at the end of Jesus’ ministry, towards the Holy Week, John interpolates it right at the beginning of Jesus’ public ministry – right after Cana in chapter 2, and so seemingly unrelated to the Holy Week in the time-line of Jesus’ story. However, from Cana Jesus points to Calvary when he announces that his “hour has not yet come”, the “hour” being his hour of glory when he is lifted up on the Cross and he draws all people to himself. The quick point here is, the various arrangements of the traditions by the four evangelists alert the readers to different theological concerns.

So we recall the fact that the sayings and acts of Our Lord were first preserved and handed down from generation to generation in oral traditions. When the Gospel writers sat down to organise their materials into a continuous story, they became a special breed of inspired editors of those traditions on the life of Jesus of Nazareth. There is no doubt that they brought to their work a divine inspiration. Equally important, however, is the fact that they also brought to their inspired writings their personal theological lenses. Furthermore, they re-told the life story of Jesus Christ using particular editorial techniques.

One of the techniques Mark employed a great deal of is the “sandwich technique” [of the A-B-A structure] by which he would begin telling a story (A), but he would then interpolate other materials by going off on a detour to a seemingly unrelated incident and finish narrating that incident (B) first, before returning to resume the original story (A). The story and that which he sandwiched in between the story ought to be read together, just as a sandwich made up of different components is intended to be consumed as one integrated whole.

The fig-cursing story, which people find confusing, is an example of a Markan sandwich in which the cursing story begins in Mark 11:12-14, makes a detour, and continues in verses 20-25, with the story of the cleansing of the Temple (verses 15-19) sandwiched in between. The same incident is recounted in Matthew 21:18-22 without the sandwich. Luke omits this story altogether.

The first question that confronts us is: How do we interpret a sandwich composition?

The answer, it seems, is easy enough: learn from sandwiches! Sandwiches are pretty much defined by the stuffing we put in between two pieces of bread. [Similarly, the Temple-cleansing incident ought to inform our interpretation of the fig-cursing.] In a real sense, the essence of a sandwich is in the stuffing. So we call it a peanut sandwich, a jam sandwich, a ham sandwich, an egg and cucumber sandwich, and so on. We do not eat a sandwich and refuse the stuffing; or else we might as well just eat two pieces of bread. But, a sandwich is not a sandwich without the two pieces of bread; or else we might just as well have the stuffing only, instead of a sandwich. Besides, there is a variety of bread to choose from and the type of bread is often pretty important too, in yielding the shape, size, texture and even the quality of the sandwich. Like the inner stuffing, the two pieces of outer bread which hold the sandwich together and give it an overall character and taste are really quite indispensable. And so, in a sandwich, every bit counts! The overall and complete package of the sandwich cannot be ignored. [And so, the incidents of fig-cursing and Temple-cleansing may mutually inform and enlighten.]

Back to the story, as Jesus and his disciples were on the way back from Bethany to the city of Jerusalem, he felt hungry. Seeing a fig tree with full leaves, he went over in the hope of finding some fruit which he could eat. Mark says “He found nothing but leaves.” As editor, Mark supplied the reason for the tree’s fruitlessness: “it was not the season for figs”. And yet, Jesus promptly put a curse of barrenness on the tree: “May no one ever eat fruit from you again.” Mark also tells us that Jesus’ disciples heard him say that.

This is a famous Gospel story, even troubling for many people. So it’s a popular subject for artists. Here’s one by Tissot.

Then they continued their journey to Jerusalem. On entering the Temple, Jesus was so angered by all the trading going on in there that he overturned the tables of the money changers and drove the traders out. That incident came to be referred to as the cleansing of the Temple on account of Jesus’ judgment that while God intended the Temple to be a “house of prayer”, it had been turned into a “den of robbers”. But was not the trading going on in the Temple both according to the law of the Temple rules and useful to pilgrims?

- First, all the business traffic going on in the Temple was sanctioned by the religious authorities. So the trading which Jesus disrupted was actually lawful.

- Besides, money-changing was a necessity, as Jewish pilgrims had to exchange their foreign coinage for the appropriate local currency. So too was dove-selling, as poor people, out of necessity, bought doves at the Temple precinct that had been certified by the religious authorities to be without blemish, for they could not afford other grander sacrifices and it was not convenient to have animals on tow while on pilgrimage.

Why then was Jesus so furious? Why did he act in a way which seemed so unreasonable?

What did Jesus intend to do in the Temple and why?

Jesus made a judgment. He judged that the religious authorities were neither faithful nor prayerful. His actions were a demonstrative condemnation against traders and ruling Temple aristocracy. In all three Synoptic Gospels, Jesus demonstrated that he detested exploitative commercial traffic and Temple-corruption.

- In naming what he saw as “a den of thieves or robbers”, Jesus was angry with the whole of this traffic on account of unconscionable trading practices conducted within the Temple precinct, at the expense of the people, especially the poor.

- Furthermore, in sanctioning such trading, the religious leaders were profiting from it all. So “a den of robbers” also carried a charge of corruption against the religious leaders who worked in cohorts with traders for profit! Temple and trade worked like hand and glove. Marketers fitted within the Temple-system. Something was seriously not right. The true law was that the Temple would be a house of worship, and now it has become a place to fleece the people.

- John’s Gospel offers an important emphasis in its choice of the Greek word “emporion” to describe the current state of the Temple. From that Greek word, the English derived “emporium” – a house of merchandise. St John is therefore more emphatic: regardless of whether the traders behaved like thieves and robbers, Jesus insisted that the Temple was a house of prayer, not a house of trade. Period. Hence, Jesus displayed such holy anger!

- As morally objectionable as it was spiritually sinister, the whole set up in its attendant circumstances acted as a terrible desecration. The Temple has been profaned. With holy anger, Jesus had to cleanse and purify the place. If “cleansing” correctly describes Jesus’ actions, it was because there was a prior “profanation“! And, if “cleansing” correctly defines what Jesus did in the Temple, then, in doing so, the Lord acted in defence of the Law, and thus in favour of the Old Covenant! He was not overturning the whole system of animal sacrifice; he was not putting an end to Temple-worship; and, he was not predicting the Temple’s destruction. The Temple was supposed to be primarily a place of worship, not primarily a marketplace. By overturning tables and causing chaos, Jesus challenged the religious authorities to be obedient to Scripture by making the Temple a house of prayer and not a den of robbers. This is a “softer” interpretation.

When evening came, again they went out of the city and got back to Bethany where Jesus stayed during that time.

The following day, Jesus and his disciples walked by that same fig tree and they noticed that the tree had already “withered away to its roots”. The use of the perfect tense shows the destruction was permanent, not just a temporary condition.

What confuses readers is the seemingly inexplicable behaviour of Jesus cursing the fig tree for not yielding him any fruit when Mark the editor said figs were not in season at the time!

To unravel this seemingly inexplicable action, one might logically assume that living in his native Palestine, Jesus knew the fruiting season of figs very well. But he also knew that there were some early figs, which were smaller. They grew from the sprouts of the previous year, would normally begin to appear as early as late March, and ripen by May or June. He knew the season. He was also hungry. He saw the lush green leaves and he expected to find some fruit, even if they were small ones. Yet, the tree yielded none. On this line of reasoning, one would appreciate Jesus being quite disgusted – all was just a flashy external show, causing great expectations, but no real substance after all!

That said, what Jesus did here was unusual for him. For starters, one could hardly find another episode where he behaved unreasonably. Furthermore, one would be hard put to locate another miracle which he performed that brought damage rather than healing. Yet, he cursed the tree, making it unable to bear fruit altogether from then on. On the face of it, his action was harsh, to say the least. We need to locate another dimension to this fig-cursing incident to aid our understanding.

What is St Mark telling us Jesus wants to say in this whole sandwich composition?

[1] Jesus the Messiah saw and pronounced judgment.

- The leafy fig tree was supposed to yield figs, just as the grand Temple was supposed to be a prayerful place. And yet, appearances of the Temple and the fig tree from a distance – which were gleaming – were contrary to their true condition – which was fruitless.

- Just as a pulse is the sign of a heartbeat, so a fruit is a sign of internal spiritual life. The missing fruit of prayer in the Temple which God has intended to be a house of prayer, parallels the missing fig.

- The fig tree “pretending” to bear fig parallels the religious leadership “pretending” to be spiritual.

- The deception of the religious leadership is revealed and condemned, just as the fruitlessness of the fig tree is revealed and condemned.

- He taught the disciples about two specific fruits of genuine faith: prayer and forgiveness, two items in spiritual life most difficult to counterfeit!

- He taught the disciples about the power of prayer, for he found prayers lacking in the Temple – “the house of prayer” – and faithfulness having been transferred onto a money-making system.

[3] Jesus rebuked fruitless lives.

- He issued a warning by performing a prophetic symbolic action, an enacted prophecy, as in Jeremiah 19:1-11, calling for repentance and change, with a promise of dire consequences otherwise.

- The promise of dire consequences was delivered by Jesus through a stunning visual effect – instantaneous withering death of the fig tree in Matthew’s account, or the same death “discovered” the following day in Mark’s sandwich-narrative. The “wow” factor must be clear to the disciples who witnessed all that – this “man” was much more than a prophet like the prophets of old. That “visual” testified to his judicial power in the Kingdom of God. He had the divine authority to pronounce judgment on religious hypocrisy and empty, fruitless religious lives.

- The key to interpreting Jesus looking for fig resides in the fact that the tree had many leaves but no fruits. The tree, then, represented a person who showed outward virtue without real sanctity, like the official religious leaders in charge of Temple worship.

- The Temple-cleansing, like the fig-tree-cursing, served as a warning to Jerusalem that, if it would not produce fruits, it would be destroyed.

What is the story telling us today?

- Jesus attacks externalism. Grand external display without internal substance is not good.

- Jesus rebukes fruitless Christian lives. God expects us to produce fruits of repentance and virtue, in season and out of season, for all seasons. The faith life of a professed Christian is always a fruitful way of life. There is nothing seasonal about that!

- Jesus warns that where there is deception in religious life, it will be revealed and his righteous anger will follow.

What might we do in response to the Word?

1. Follow Jesus the lay person by freeing ourselves from wrongful attachments, for kingdom-advancement:

- Refuse to be flashy and yet empty.

- Have a conscience, and not be profit-centred all the time.

- Don’t just be politically correct at all times, but learn about righteous anger and speak up sometimes.

- Living as we do in revolutionary times, contribute to a Tahrir Square within the Church community for the promotion of truth and justice.

2. Learn from Jesus’ condemnation of the Temple money-making exploits by operating a moral-budget:

- Look seriously into “how” we gather funds, in our private enterprises and in the faith community. Our method must be upright. And the poor must never be unduly taxed.

- Then, look seriously into “how” we apply the funds that we have gathered for ourselves and for the faith community. Christian stewardship demands a conscientious application of funds in favour of the needy. Be conscious that our budget (personal or communal) is always a moral document! This is where an intentionally Christian conversation begins in the home and in the parish.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, May 2011. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.