Then he [Jesus] said to Thomas, “Put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side; do not be faithless, but believing” [John 20:27].

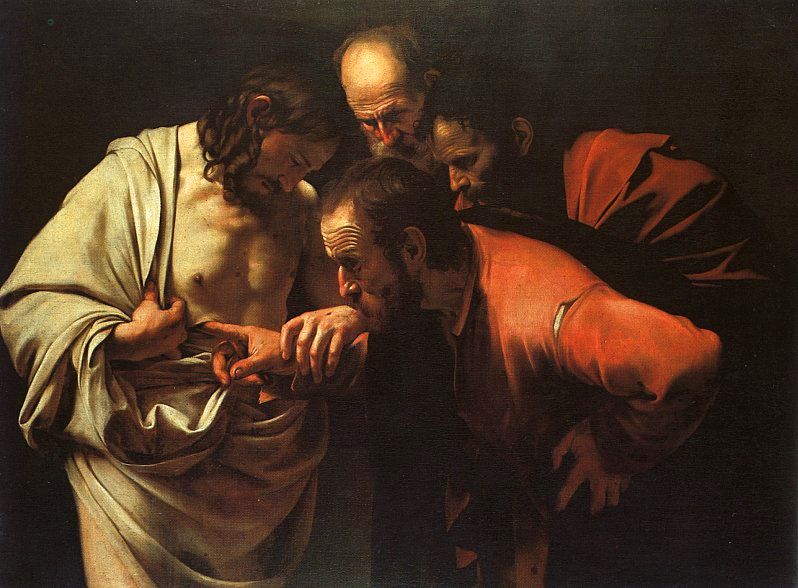

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. Caravaggio, 1602.

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. Caravaggio, 1602.

Incarnation is a very concrete event.

Saint John the Evangelist captures it best: The Word took flesh and pitched tent amongst us, and the first disciples had beheld his glory.

When, then, the time came for Jesus the Son of God to suffer and die, the reality was too harsh and disturbing for the disciples. Death was death. The story had ended. The disciples were beyond disappointment; their hopes had completely shattered. So when the women came with news of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead, the disciples’ first reaction was that “these women are talking nonsense”. And when Thomas was told of Christ’s appearance to them in his absence, his vehement incredulity imputed the same “nonsense” to their “incoherent” words, insisting instead upon unequivocal evidence in the flesh. “Unless I see in his hands the print of the nails, and place my finger in the mark of the nails, and place my hand in his side, I will not believe” [John 20:25]. Thomas knew what evidence would suffice. Nothing short of Jesus’ wounds and scars would do! He demanded something concrete, in the flesh, something real. Unknowingly, Thomas was insistent upon Jesus’ physical wounds and scars precisely because of his own spiritual wounds and scars!

To be sure, we can access this story at different levels.

At the level of theology and belief, this is the best antidote against any heresy that leans heavily on Jesus’ divinity alone while discounting his humanity. At the level of spirituality and pastoral ministry, it demands a balanced approach where worship, incense and holy hours are seen as meaningful only if these are combined with going out there and getting one’s hands and feet dirty, so to speak, in concrete outreach. So a pastoral ministry that is theologically sound would insist on words being proportionate to deeds, just as a pastoral ministry that is spiritually truthful would see words preached and prayers said enacted in real life.

Soon after the passing of the first apostles, a heresy cropped up in the early church in the form of Docetic teaching. Docetism, from the Greek word dokeo, which means “to seem” or “to appear”, is the teaching that Jesus only seemed to be Incarnate. This teaching fell far short of a wholesome understanding of the two natures of Christ best formulated at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 in terms of the hypostatic union of both the human and divine natures. In docetic teaching, however, Jesus was not really “in the flesh”, his physical appearance being just that – an appearance – and he only appeared to, but did not really, suffer anything. How could he? God being God could not suffer, the docetists argued.

One of the things which the so-called doubting Thomas episode does, and indeed much of the resurrection narrative in the Gospels as well, is to provide us an antidote to this heresy. Everything was so physical! Jesus Christ has come in the flesh. But we suspect most of us too, and not just the docetists, could use a good jab in the arm from Dr Paul Brand, the renowned surgeon gifted with a profound grasp of the spiritual metaphors contained in the human body. Books like Fearfully and Wonderfully Made and In His Image which Brand co-authored with Philip Yancey are marvelously rich depositories of insights linking the human anatomy to faith and spirituality.

“Some people go to concerts and athletic events to watch the performance; I go to watch hands,” Brand wrote. In wondrous amazement of God taking on the form of an infant with “tiny, jerky hands of a newborn,” he remembers the paradox expressed by G. K. Chesterton: “The hands that had made the sun and stars were too small to reach the huge heads of the cattle.” For some years, they would remain too small “to change his own clothes or put food in his mouth. Like every baby, he had miniature fingernails and wrinkles around the knuckles, and soft skin that had never known abrasion or roughness. God’s Son experienced infant helplessness.”

From adolescence, Jesus learned carpentry from his father Joseph. “His skin must have developed many calluses and tender spots.” As the Galilean healer, the Bible tells us strength flowed from his hands when he healed people. Healing miracles were usually performed by Jesus not en masse, but rather by touching each person one by one. By his touch, the blind saw, the lame walked, the deaf heard. With a remarkable career working with lepers, Brand underscored Jesus “touching those with leprosy – people no one else would touch. In small and personal ways, his hands set right what had been disrupted in Creation.”

Then came the mind-balking scene that forever changed the world, the crucifixion, when Jesus’ hands were pinioned on the cross. The hands that had done so much good were taken, one at a time, and pierced through with a nail, without anesthetics of course! His cry from the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” is the cry of deep, genuine, horrible, human anguish! It is the cry of the suffering humanity in its deepest moment of desolation.

It is the cry of the suffering humanity down through the ages – crying because the suffering is cruel and real, and questioning because it longs for the consoling hands of God who tarries, but still addressing God like the psalmist because, after all, the whole being trusts in God. Clearly, the Gospel of Jesus was anything but ethereal. For two thousand years, historians have recorded and Christians have intoned, “He suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried.” It was concrete. It was historical.

Pinioned on the cross, Jesus’ body weight hung from his hands, tearing tissues and releasing blood. As helpless as he was in a manger in Bethlehem, the completely helpless Son of God hung paralyzed at Golgotha. His disciples, who had hoped he was the Messiah, cowered in safe hiding or drifted away. The fear was genuine just as the crucifixion was cruel and real.

But Jesus appeared again, in his resurrected state. Thomas, severely wounded interiorly, knew he could not possibly reach any renewed faith in the Lord without the solid backing of wounds and scars. So he scoffed at other illusionary faiths and beliefs. Only upon Jesus’ invitation to trace his wounds and scars with Thomas’ own fingers, could Thomas respond in faith. And what a faith-response it was, for it was doubly complete: “My Lord and my God!” It is the first occasion recorded in Scriptures where one of Jesus’ disciples directly addressed him as God. And the recognition came only in the wake of Jesus’ wounds and scars. Very concrete. Very tactile. Nothing less would do.

Throughout history, suffering humanity yearns to know that God the Supreme Being knows our suffering and feels our pain. People who suffer want to know that the pains they endure on earth are not meaningless. They want to know that their prayers and gut-wrenching cries are heard. In the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, God has demonstrated that he knows our suffering and he feels our pain, not just in nice words and beautiful theory, but in having personally undergone the excruciating experience of being scourged, slapped, thorn-crowned, spat on, stripped, utterly humiliated in every possible way, and publicly crucified. Christ has left us with a permanent image of scars in each hand to remind us of his time here, of his complete understanding of our pain, and of how he has absorbed them into himself as a lasting image of wounded humanity and cried on its behalf on the Cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” [Mark 15:34]. He knows what life on earth is like. He has been here. His wounds and scars prove it.

Post-resurrection apostles understood this well. So the constant theme in Peter’s letters was the cross of Christ: “But rejoice in so far as you share Christ’s sufferings, that you may also rejoice and be glad when his glory is revealed” (1 Peter 4:13). Paul, too, understood his own sufferings were to complete Jesus’ suffering on earth: “Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is the church” (Col 1:24).

Classical Christian paintings showing graphic representation of Thomas putting his finger into Jesus’ side are so real that they make us cringe in discomfort, as do Caravaggio’s and Guercino’s pieces. In Asia, Li Wei San has captured this Gospel essence in his piece titled “Nail Mark”. It captured the time of the great cultural revolution in China. With plenty of misguided zeal under the Communist rule, life was chaotic. Many went through unspeakable human suffering. An elderly Christian pastor, whom the officials labelled “bourgeois” and “dangerous”, was banished to hard labour in the countryside. In the middle of the night, as the old pastor was alone reading the Lord’s passion in the Bible, a stranger came to visit, but he did not recognize the visitor. As he was talking to the stranger, suddenly he saw the nail marks on his hands and exclaimed: “You are my Lord!” See how they smile understandingly as they examine each others’ wounds.

The prophets of old had foretold, “By His wounds, we are healed” (Isaiah 53:5; 1 Peter 2:24). The Cross, in Pope John Paul II’s spirituality, is like “a touch of eternal love upon the most painful wounds” of human existence on this earth. In the Christian faith, we have a resource, originating from God, of immense consolation. And yet, even more profoundly, the Christian faith is characterized by a great commission to go out and tell the whole world about this consolation. We are to bring to all humanity, afflicted as it is by evils, with hope from the Risen Christ. Our mission is to never shy away from the wounds and scars of the world, but to stay there, and to put our finger right where it hurts, and be in healing communion.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, May 2011. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.