And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.’ [Matthew 25:40, NRSV]

In Search of the Spirit of a Saint [1]

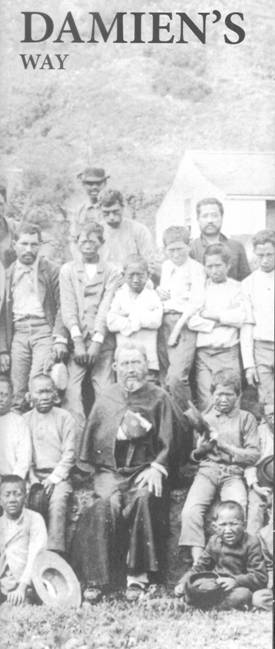

On October 11, 2009, the famous leper priest, Fr. Peter Damian, was declared a saint together with four others at a Vatican ceremony, and named St Damian of Molokai, Hawaii.

In the late 80s and for the most part of the 90s, we spent some nine years working through our three cycles of theological formation at the Theology Faculty of the renowned and oldest Catholic University in the world (founded in 1425), the Catholic University of Louvain (spelt Leuven in Flemish), Belgium. When we returned for a visit last October, the City was decked out with flags and banners carrying the slogan “DAMIAN INSPIRES”. Photos of Damian were exhibited at strategic points. Louvain became a veritable DAMIAN CITY and tour buses lined the street outside the church where his body is entombed.

What is a saint? Throughout Christian history, the Catholic Church has recognized in a particular way those of her members that have, through God’s grace, lived lives of great charity and heroic virtues. Filled with faith, hope and charity, they are held up by the Church as worthy of emulation. Saints are people who had given of themselves totally without “calculation or personal gain,” according to Pope Benedict XVI. “Their perfection, in the logic of a faith that is humanly incomprehensible at times, consists in no longer placing themselves at the center, but choosing to go against the flow and live according to the Gospel.”

Born Joseph de Veuster in 1840 in Tremelo, Belgium, the future saint took the name Damian after following his oldest brother’s footsteps and joining the missionary Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary (SS CC). That saw the end of his father’s plan that he should take charge of the family’s farming business.

Damian’s brother had planned to go to the missions in the Hawaiian Islands but when he became ill, Damian requested permission to take his place. After arriving in Honolulu in 1864, he served on the Big Island for nine years before volunteering to go to the settlement at Molokai, where about 8,000 lepers had been banished for life on strict prohibition against leaving as well as contact with the outside world. Initially, Damian had volunteered to minister to the victims on a rotation basis but he ended up staying there for good.

The conditions in which Damian worked were really bad. Forced into exile on five square miles of windswept land, infected people were so feared and reviled that they were forced overboard from the boat that carried them to the island right into the wild currents and waves. Many drowned before reaching the shore, unable to let go of things they carried with them. Those who survived the swim to shore were the poor who had little worldly possessions to weigh them down. Once on shore, the survivors were confronted with neither medicine and housing nor law and order. Kalaupapa on Molokai was truly a lawless and miserable settlement. Many died in the first years through exposure to the elements and lack of basic supplies, and were buried in unmarked graves along the shore.

Designated a Leper Colony, Kalaupapa was a “suburb of hell” when the 33-year-old Damian first arrived. From then on he struggled with a constant shortage of supplies, medical treatment, food and housing. Conditions were so poor that Damian wrote in late 1874: “From morning to night, I am amidst heartbreaking physical and moral misery”. The deplorable conditions, immense suffering and hopelessness of the inhabitants he found there were the stuff for books and films. And yet, he spent sixteen years on that settlement, ultimately succumbing to Hansen’s disease at age 49 on April 15, 1889, four years after being diagnosed with the disease.

Damian’s body was exhumed and sent back to Belgium in 1936 and interred in a marble tomb in a crypt at St Anthony’s Chapel (also known to pilgrims as St Joseph’s Sanctuary) in Louvain. In 1995, Pope John Paul II, on the occasion of Damian’s beatification, sent bones from his right hand back to Molokai to be reburied in his original grave. His right hand was chosen because it was the hand that blessed, cared for, and bandaged the sick.

Introduced to the crypt by Fr. Gerry Gleeson, an Australian doctoral candidate in philosophy at the time, soon after our arrival in September 1989, we attended our first Mass on Belgian soil there. From then on, the Damian-dimension has factored into our theology. From our perspective, all critical learning – and Louvain boasts of nothing if not critical institutions of learning, its famous Belgian pralines (chocolate) and Stella Artoi (beer) notwithstanding – is seriously wanting without taking into account the challenge of the Damian-factor in radical Christian living.

What we call the “Damian-factor” in Christian living incorporates the best of the Damian spirit that has many elements some of which we identify here.

1. A life of voluntary sacrifice, dedication and perseverance

Taking after his Lord, Damian’s sacrifice was voluntary. He went on to do what he felt he needed to do, whatever the cost, in obedience to the Gospel.

“We live in a world with so few heroes, examples of what we can be,” said Father Herman Gomes of St. Ann’s Church in Kaneohe, Hawaii, who has been giving talks on Father Damian since 1994 to churches and school groups. “He is the model. You look at a life of dedication and perseverance, how can you not be inspired, amazed and spurred on to do that for yourself?” In St Damian, the Church proposes an example to all those who find sense for their life in the Gospel and who wish to bring the Good News to the poor of our time.

2. Giving voice to the voiceless, dignity to the sick

Damian spoke up against the evil committed against the poor. He never ceased to confront the civil authorities for banishing the lepers and for failing to provide for even their basic welfare, forcing them all to die in inhuman conditions. Not unlike Queen Esther of whom we wrote in our last post, Damian spoke up and forced it upon the conscience of the powerful to hear the voice of the voiceless, even though he spoke to deaf ears most of the time. One can see why he wasn’t too popular with the authorities of church and state for his constant interceding on behalf of the poor, so much so that even his local religious superior once reported him to the Order’s central government in Europe for being “excessive in his demands on behalf of his lepers”.

The eventual positive response was a long time coming, to be exact, 39 years overdue. Since the 1940s, sulfide drugs were discovered to stop the spread of Hansen’s disease. Yet the patients of Kalaupapa were still forced to remain isolated until 1969. Only in 2008 did the state legislature of Hawaii pass a two-and-a-half page resolution to offer a sincere apology to the people of Kalaupapa for the actions of the state through the Department of Health. Verbally apologizing to the community, Senator J. Kalani English said: “We’re sorry. We’re sorry for the treatment, we’re sorry for the suffering. Sometimes we act irrationally and the government has done that. From 1948 to 1969, there was no real reason to keep you isolated; it was the government being afraid, people not understanding.”

President Barack Obama expressed his “deep admiration” for St. Damian and offered his prayers for all those celebrating the priest’s “extraordinary life and witness”. With roots in Hawaii, Obama said: “Fr. Damien has also earned a special place in the hearts of Hawaiians. I recall many stories from my youth about his tireless work there to care for those suffering from leprosy who had been cast out. Following in the steps of Jesus’ ministry to the lepers, Fr. Damien challenged the stigmatizing effects of the disease, giving voice to the voiceless and ultimately sacrificing his own life to bring dignity to so many.”

On a different front, in response to the scathing and derogatory remarks made by Dr. Hyde on Damian, the renowned writer, Robert Louis Stevenson, defended Damian in an impassioned Open Letter to Dr Hyde which has become a classic. Dr. Hyde and others’ accusations had since been seen by the rest of the world as coming from bigotry and envy, and understood as ignorance of the time that the disease of leprosy could be transmitted solely by sexual contact with someone suffering from the disease.

3. He practised what we say in theology – solidarity and co-humanity with the poor

Solidarity and co-humanity with the poor and the marginalized ranked first in Damian’s scale of values. To be in solidarity with the lepers, Damian identified with them. He smoked their pipes and ate from their dishes – a sure way to contract the disease himself and become one like them. From the moment he contracted the disease in 1885, he was able to identify completely with them and spoke in terms of “We lepers”. His solidarity with the people he came to serve was complete.

4. A spirituality incarnated in menial work

For sixteen years, like his Lord who got down from his seat at the head of the table to wash his disciples’ feet, Damian cleaned and bandaged wounds, amputated gangrenous limbs, built more than three hundred simple homes, erected 8 churches and chapels, laid a pipeline to bring fresh water to the settlement, made more that 1600 coffins, dug graves and buried the dead. It was only shortly before his death that help arrived in the form of Franciscan nuns, as well as some priests from his Congregation and two doggedly determined lay volunteers, Joseph Dutton and James Sinnett. A biographer described him as “a vigorous, forceful, impellent man with a generous heart in the prime of life and a jack of all trades, carpenter, mason, baker, farmer, medico and nurse, no lazy bone in the makeup of his manhood, busy from morning till nightfall”. This saint, it is clear, incarnated his spirituality in actual menial work. Truly a servant of God, he lived and died a servant of suffering humanity.

5. A raw hard-edged hero and saint

Listen to the words of an artist, Rev. Keith Drury, who created a style called artobiography: “When asked to create an art piece on Damien, I immediately decided that the piece should not be painted with soft hues, for there is nothing soft about leprosy, Molokai or the life Fr Damien lived. So the paint strokes were often delivered with edges and hard areas which do not try to gently mix with their surroundings. For that reason I chose to paint the older weathered Fr Damien rather than the softer images of him as a younger man. Fr Damien had hard edges as the letter penned by Robert Louis Stevenson indicates and as an artist I have not tried to romanticise him but rather to present him as the raw hard edged hero and Saint he was.”

6. He did theology and ministry on his knees

Revealing Damian’s spiritual secret, Bishop Brendan Comiskey, ss.cc., wrote: “It is almost impossible to grasp how one man could accomplish what Father Damien accomplished during his lifetime. There is, however, one aspect of his life that has received less attention. In spite of the extraordinary demands made on him, he reserved the first hours of every day for prayer and spiritual reflection. His constant companion was a 15th century devotional book, The Imitation of Christ, which called for humility and austerity and a continuing self-examination. Damien took the lessons of the book to heart; even when he was dying he continued to sleep on a straw mattress on the floor. ‘Let it be our chief study,’ the Imitation counsels, ‘to meditate on the life of Jesus Christ…. Jesus has many lovers of his heavenly kingdom, but few who are willing to bear his cross’. How well Damien learned that lesson. This is a side of the new saint that is seldom referred to. This is Damien’s secret.” From where we stand, Damian teaches that, in addition to doing so through the eyes of the poor, the correct way to do theology, or to study the Bible, is on our knees. Sacrificial ministry flows from there.

At a Mass with members of the International Theological Commission on 1 December 2009, Pope Benedict XVI described the figure of the true theologian as one who does not succumb to the temptation of using the measure of his own intelligence to fathom the mystery of God. In the study of Holy Scripture, for example, it is of no help if one became a specialist or a master of the faith, able to penetrate into the details of the history of salvation, “but is unable to see the mystery in itself, the central nucleus: that Christ truly was the Son of God”. But, among “a long list of men and women who were capable of humility and of reaching the truth,” he mentioned St. Therese of Lisieux and St. Damian de Veuster, “little people who were also wise”, models from which to draw inspiration because “they were touched in the depths of their heart”.

7. The Damian-factor urges us to find our own Molokai

Damian’s story reveals an extraordinary radical witness. The problem is, what can such an extraordinary life possibly say to us today? After all, few of us are going to enter religious order, or work with the very ill and forgotten in our own country, let alone doing so in distant foreign land.

There is, first of all, the problem of being in total awe of his sacrifice. Great is the danger of confusing the signpost or finger with the source of grace. Karl Rahner, the famous twentieth-century Jesuit theologian, has repeatedly said that the church must proclaim the holiness of its greatest members precisely because it has the duty of proclaiming the grace of God and what that grace accomplishes in people like Damian. However, the important thing to remember is that everybody and every thing holy are only signposts or fingers pointing beyond themselves to God, the source of all goodness and holiness. We would be fools if we stayed at the level of the finger! In the beatification homily in Rome on 4 June 1995, Pope John Paul II said: “Holiness is not perfection according to human criteria; it is not reserved for a small number of exceptional persons. It is for everyone; it is the Lord who brings us to holiness, when we are willing to collaborate in the salvation of the world for the glory of God, despite our sin and our sometimes rebellious temperament.”

There is, second of all, a need to link and apply the Damian factor to a variety of sacrifices many believers would make in real life. James Martin, SJ, does just that: “The story of Damien, like the lives of so many saints, can seem while noble, largely irrelevant to our own. Yet by reading the saints’ lives carefully one can always find profound resonances with the lives of everyday believers. What parent is not called upon to minister to a child when he or she falls ill, even at the risk of contracting an illness? Who among us is not called to stand with the outcast, with those whom polite society shuns either literally or metaphorically? Who is not called to do works of charity and love that may remain utterly hidden from the rest of the world. Think of the husband or wife caring for the spouse with Alzheimer’s. Is this not a hidden act of charity? Think of the parent caring for a child with a cancer or an incurable illness. Even if the parent does not contract the illness, is this not a heroic deed? Damien is not as far from us as many would think.”

There is, third of all, therefore, no necessity for us who live in the twenty-first century to travel to a far-flung remote island to put the Damian spirit into practice. We can do so, right at our own little insignificant places, unknown to the outside world. And so, to those who visited Mother Teresa and asked permission to work alongside her in Calcutta, she would sometimes say, “Find your own Calcutta.” Likewise, we must hear St. Damian saying to us, “Find your own Molokai.” That is, care for the poor right where we are.

Today the spirit of St Damian continues in India, Taiwan, China and many Asian countries. His spirit is seen in numerous initiatives, including standing and mobile medical clinics, rehabilitation programs, nutrition programs, housing projects, vocational training and education. There are those who are vested with a clear vision and a dogged determination to eliminate human sufferings in order to revive and enhance the spirit of equality and dignity. They become a gift from God, bringing hope and Christian love to the marginalized poorest of the poor.

In India, a national weekly, the Kerela-based “The Week”, has named a Catholic priest – Father Christudas – as its “2009 man of the year,” in recognition of his efforts to restore the life of some 50,000 leprosy patients in Bihar. “He is a one-man army who gave 50,000 lepers and their families a fresh start in life. He gave them treatment, dignity and more importantly the will to live and smile again,” The Week’s cover story said. Christudas’s center, spreading over 8 hectares of land, grows wheat and runs a poultry farm that meets 40 percent of its needs. The complex includes a school, hostel, hospital, work center and a village of 200 families – all cured patients. The integration of the leprosy patients and their families in mainstream society is “the sole purpose of my work,” says the priest.

8. The Damian spirit is always a timely teaching tool

“Lepers” have been reviled since Biblical times, and many of Jesus’ most well-known miracles involved healing people suffering from leprosy. There is great scope for the utilization of the Damian story for teaching in schools and in society.

From Damian, kids learn that everyone can do something to help the less fortunate, starting with something small. His life is a call for us to de-stigmatise leprosy now. Leprosy is easily curable today and no one should die of it, yet many do. The problem with leprosy is that it is located in under-developed countries. Its most punishing effect is the social stigma it carries, a stigma now assigned to many suffering from AIDS, as though the disease were not enough. HIV/AIDS patients experience the very same bigotry, hatred, ignorance and ostracisation that Damian and the lepers of Molokai experienced.

Once, Johan Verstraeten, a Moral Theology professor in Leuven, received a group of high-powered business executives from Brussels for a study-day. These busy personalities had come to Leuven expecting to listen to brilliant lectures on business ethics. Instead, Verstraeten brought them to Damian’s crypt for a silent meditation. Confronted with Damian’s tomb, and photographs of him diseased and dying, they meditated on questions such as these: “Given your privileged position in society as heads of business organizations, how would you now run your businesses in the midst of human suffering, in the light of the Damian-factor? What contributions would you make to humanity on behalf of your business enterprises? Would your life just be business-as-usual?” At the end of their study-day, the group thanked Verstraeten profusely, grateful for the most meaningful study-day they had ever had.

On our part, the Damian crypt has edged an indelible mark on our souls since 1989. Inscribed on the plaque placed next to the tomb is a quote from St Damian which profoundly reveals his spirit. He said that what gave him the greatest pleasure in life was the privilege to serve those whom society considered the least and the most insignificant. Of those whom society rejected, he had perceived to be the most beloved little children of God and he faithfully lived his life as a humble instrument of that love. He died in 1889 “the happiest missionary in the world”.

Finally, we can make the prayer of a Hawaii Catholic Bishop, Larry Silva, our own: “We pray that Father Damien will inspire us all to reach out to those most in need, to make a real difference in their lives, and to serve them with the love of Christ.”

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, February 2010.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.