“Jesus said, ‘My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight to prevent my arrest by the Jewish leaders. But now my kingdom is from another place.’” [John 18:36]

Today is the International Day of Peace. Established by the United Nations in 1981, this world day of peace provides an opportunity for individuals, organizations and nations to create practical acts of peace on a shared date. The idea is to give peace a chance.

In the Gospels, Jesus indicates that the kingdom of God is distinct from the empires of this world. In God’s kingdom, disciples do not resort to violence. In his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus calls those blessed who are peace makers [Matthew 5:9]. Learning from Isaiah 2:3-5, Christians beat swords into plowshares in promotion of peace. In Ephesians 6:10-18 and 2 Corinthians 10:3-4, Christians are reminded that “our battle is not against flesh and blood,” that “we do not wage war as the world does,” for the “weapons we fight with are not the weapons of the world.” Clearly, both texts utilize military language and intentionally subvert it. While nations and empires would fight against flesh and blood enemies, people of the kingdom of God use God’s spiritual armour against demonic powers.

Far from having peace in the third millennium, the ubiquitous presence of war and atrocities in all corners of the earth, and the ferocity with which people on both sides of aggression denounce and hate the other, have become so commonplace that we tend to sink into helpless indifference. Worse yet, closer home to our daily existence, we encounter violence in covetousness and the will to control others, to reduce their dignity in order to elevate one’s own.

How might Christians try to reduce this level of “violence” in their own lives?

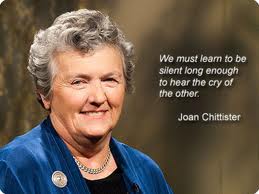

We turn to a reflection by Sr. Joan Chittister for an answer. Steeped in Benedictine spirituality, Sr. Joan suggests an inner journey to peace. She emphasizes the need to listen. Silence, she points out, creates for us that essential space to think and thinking then allows us to grow in wisdom and come to an understanding that we do not have all the answers. Then, humility has a chance to grow through which we come to realise that we are all pilgrims on the same journey searching for the Holy Other. But, it will take no less than a discipline to practice silence and solitude which has been all but lost to us busy inhabitants of a noisy twenty-first century world.

The video on her reflection is a marvelous gift, and may be accessed on YouTube. The following is our transcription of that video which we hope might aid on-going reflection and dialogue.

I heard two children talking recently and suddenly realized what children need from us. I also realized that we are giving them just the opposite. In these two children, I heard a microcosm of a world at war. I was talking to children, to innocence, and discovered that they were not innocent about our wars at all. Children are in fact their carriers. These two children know just whom to hate. They were Irish children and they resented the Americans for their money, and they hated the English for their history.

“I hate them,” the one child said simply.

“Me, too,” the other child agreed.

And it was final. Schooled in someone else’s attitude, they were impervious to any other one.

I saw in their faces all the children of the world – Hutu children and Serbian children and Palestinian children, children who were learning to hate Tutsi children and Bosnian children and Jewish children. They had all been born into a world of adult enemies, which they inherited along with the land under their feet. They had inherited the sins of their ancestors, and these sins festered like time bombs within them until years later, those same weapons would surely go off in them too.

Clearly, it is the lack of peace within ourselves that we are passing on to our children. If we do not have a rich inner life, we will want to have the tinsel and glitter of the world around us, and someone else’s money to get it too. If we are insecure, we want to control others. If we are not at peace with our own life, we will make combat with the people around us. And if we do not learn to face our own struggles, we will never have compassion for the struggles of others.

Peace comes then when we learn what the spirit within us is trying to teach us.

When we feel rejected, we learn to seek the love above all loves in life.

The spirit is trying to teach us that when we are threatened by differences, we must come to realize that otherness is what stretches us beyond the narrowness of sameness.

Instead, the desire for conquest comes, when I try to shape the world to my own limited ideas of it. Then, differences begin to be a threat, rather than a promise of an inspiring new possibilities, or daring new experiences in life. Then, we set out to mold the rest of the world to our own small selves. We rape the planet and make war against strangers and build our private little laws higher and higher and higher.

To feel good about ourselves, we measure ourselves against other races and sexes, religions and cultures and call them lesser. Call them enemy.

We entomb ourselves in ourselves. So brown people remain enemies for generation after generation; and white people stay a menace to all our lives; and strong women threaten our worldview; and the children of this generation become the adversaries of the next one.

The question is then: What is the way to peace?

Blaise Pascal wrote once, “The unhappiness of a person resides in one thing – to be unable to remain peacefully in a room.”

It is silence and solitude, in other words, that bring us face to face with ourselves and the inner wars we must win to become truly peaceful people.

Then, understanding myself, I can understand everyone else as well.

There is a major social obstacle, however, to a development of a spirituality of peace in this time, in our time. The fear of silence and solitude looms like cliffs in the modern human psyche. And noise becomes what protects us from becoming ourselves. While it is only a phantom memory in this culture, some generations among us have had no experience of silence at all.

Spiritual peace has been driven out by noise pollution endemic and invasive. There is music in the elevators and PA systems in the halls and people talking loudly in cellular phones everywhere, in offices and restaurants and kitchens and bedrooms, while the ubiquitous television spills talk devoid of thought and people shout above it about other things. There are loudspeakers in boats now, so lakes are not safe. There are rock concerts in the countryside, so the mountains are now not safe. There are telephones in bathrooms now, so the shower is not safe. We don’t think any more. We are wired for sound. Indeed, silence is the lost spiritual art of this society. Clamour and struggle have replaced it.

But the great spiritual traditions are all clear about the role of silence in the spiritual life.

“Elder, give me a word,” a seeker begged the desert monastic.

And the holy one said, “My word to you is, go into your cell and your cell will teach you everything.”

That point is clear and simple: All your answers are within you. And so are the questions, the questions that no one can ask of you but you. Everything else in the spiritual life is mere formula, mere exercise. It is the questions and the answers that are around you within each of us that in the end will grow our souls. Then, we will get to know ourselves. Then, we will blush at what we see. Then, we will lose our self-righteousness and come to peace.

Silence does more than confront us with ourselves, however. Silence makes us wise.

Knowing our struggles, we come to reverent the struggles of others.

Knowing our own failures, we are in awe of their successes, less quick to condemn, less intent on punishing, less certain of all our damaging certainties.

Make no doubt about it. To listen for the voice of God and to wrestle with the self is the nucleus of the spirituality of peace. It may o fact be what is most missing in a century saturated with information, sated with noise, smothered in struggle, but short on reflection and aching for peace.

Once upon a time, a disciple asked, “How shall I experience oneness with creation?” and the elder answered, “By listening.”

“But how am I to listen?” the disciple asked. And the elder taught: “Become an ear that pays attention to everything the universe is saying. The moment you hear something you yourself are saying, stop.”

Peace will come when we expand our minds to listen to the noise within us that needs quieting, and the wisdom from outside ourselves that needs to be learned.

Then, we will have something to leave the children, besides hate, besides war, besides turmoil.

Then peace will come.

[L] Travelling an inner journey. [2] Let Us Beat Swords into Plowshares, a sculpture by Evgeniy Vuchetich in the United Nations Art Collection

[* This post, originally scheduled for January 1, was inadvertently shifted.]

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, January 2013. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.