He also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt: ‘Two men went up to the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax-collector. The Pharisee, standing by himself, was praying thus, “God, I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even like this tax-collector. I fast twice a week; I give a tenth of all my income.” But the tax-collector, standing far off, would not even look up to heaven, but was beating his breast and saying, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!” I tell you, this man went down to his home justified rather than the other; for all who exalt themselves will be humbled, but all who humble themselves will be exalted.’ [Luke 18: 9-14]

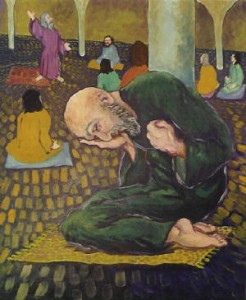

[L] The Pharisee making his self-righteous prayer. [R] The Publican praying with a repentant and contrite heart.

Prayer at its best is a dialogue from the heart with God. It has been poetically described as “a spiritual breathing of the soul”, even when intense struggles are involved.

By word and by example, Christ upon request from his disciples on “how to pray”, taught them what we now call the Lord’s Prayer [Matthew 6: 9-13; Luke 11:1-5]. There, integrating the “how to” with “what to”, the Lord gave his disciples an example of a model prayer. The “how to” included the spirit of penitence, of acceptance of God as our Provider, of trust, humility and asking for only the basic sustenance for life day by day.

In Luke 18, Jesus further gives a parabolic teaching on the right way to pray that may take us home justified. The parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector praying in the Temple seems simple and straightforward enough: one was arrogant, the other humble; the second was forgiven, the first remained in sin.

On reflection, however, the picture becomes neither simple nor straightforward and speaks much to our own approaches to prayer. Between the Pharisee and the tax collector, who was good at praying? Who was a model for praying? That this story was an illustration Jesus used to teach his disciples about prayers makes for an important case study.

Two Complications

Complications set in when we take note of two things.

- First, both the Pharisee and the tax collector pray for themselves, neither of them prays for the needs of others, and each bares himself before God.

To turn to God for our needs and then to bare oneself to God marks our spiritual strength. However, we too, tend at times to be so focused on our own needs that we forget about the needs of others. In the parable, neither man was condemned for not praying for the needs of the other, however. Do we seem to share pretty much the same traits as the two characters in this story?

- Second, the Pharisee in the story was in fact a pretty faithful Jew.

Before we start sneering at the Pharisee for his “self-righteous” style of prayer, recall that what he did was pretty standard and acceptable lore of all good Jews. Thanking God that he was not like others was not necessarily an expression of disdain for others; it was for all its seeming “inappropriate arrogance” a humble way of thanking God for his being made in God’s image and likeness. To this day, in fact, the Morning Prayer for Orthodox Jewish men includes a prayer with these words: “Blessed art thou, O Lord our God, King of the Universe, who hast not made me a gentile, … a slave, … a woman.”

Then, the Pharisee went on to account to God that he paid tithes on all his income, that he was “not grasping, unjust, adulterous like the rest of mankind,” and that, particularly, he was “not like this tax collector here.” Tax collectors during the Roman rule were hated for colluding with the Roman occupiers in tax collection and even blood-sucking fellow Jews, and the Pharisee was no different from all other Jews of the time for considering them “the pit of humanity”. And, unlike this tax collector, he was a Jew who met all the requirements laid on him by the Mosaic law, and probably beyond. He was clearly a faithful Jew, and you can’t fault him for that. In fact, anyone who saw and heard him pray in the Temple would have esteemed him as a good and upright and even spiritual person.

So, what could be wrong with his prayer that rendered him “unjustified” while that seemingly rotten tax collector went away “at rights with God”? Could it be that Jesus considered “the system”, “the mentality”, and “the culture” of the religious elites of whom the Pharisee was a member somehow faulty? Could it be that Jesus considered the familiar, auto-drive or, to use the computer language the “default” prayer-system of the religious elites of whom the Pharisee formed a part, including its underlying mentality, and the very culture that nurtured it, seriously faulty? Was it a case of a systemic corruption of what good praying ought to be? Might Jesus be challenging his disciples to think about the “how” of prayer?

Three Things on How to Pray

Might it not be that Jesus was pointing to three things on how to pray?

- First, do not disdain others’ needs to pray as the Pharisee apparently did.

Perhaps what the Pharisee was implicitly “guilty” of was a disdain for others’ needs. If he, the Pharisee, had needs to approach God with, did not the tax collector have the right to approach God with his needs as well?

- Second, when praying to God, do not presume to judge others but leave that to God.

The Pharisee’s “not like this tax collector” has usurped God’s exclusive role as Judge.

- But third, and most importantly, always approach God as a humble penitent.

The path to God is humility and repentance. The prophet Isaiah calls us to recognize our sinfulness as he emphatically insists on the ongoing worthlessness of our righteousness :

- “But we are all as an unclean thing, and all our righteousnesses are as filthy rags; and we all do fade as a leaf; and our iniquities, like the wind, have taken us away” [Isaiah 64:6].

And the Book of Job exposes us to the utter futility and danger of our self-justification:

- “If I justify myself, mine own mouth shall condemn me; if I say, I am perfect, it shall also prove me perverse” [Job 9:20].

If the Pharisee and the tax collector share some similarities in their style of prayers, they are clearly set apart from each other in their approach to the judgment seat of God. The puffed-up “I am not like …” of the Pharisee contrasts sharply with the breast-beating mea culpa of the tax collector who, “not daring even to raise his eyes to heaven”, said, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner.”

There is in the parable a condemnation of sinless-presumption. John sets it out as it is:

- If we claim to be without sin, we deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us. If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness. If we claim we have not sinned, we make him out to be a liar and his word is not in us. [1 John 1:8-10]

There is here too a condemnation of pride and supercilious attitude. Of the six things the Lord hates and seven that he detests, the wisdom writers in Proverbs ranks pride ahead of even murder [see Proverbs 6:16-19]. Pride promotes self-sufficiency, packing God off to the margins of our existence. Could it be that our self-centered society is quietly influencing us and placing us in greater risks than we realize? The Book of Proverbs suggests that pride has the capability of destroying our lives: “Pride goes before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall” [16:18]. Translated, it warns that crash follows pride, and the bigger the ego, the harder the fall. The spiritual pride in the Pharisee that blocks his justification, depending as he did on his own merits rather than on God’s unearned grace, serves as a warning to us all who struggle with this destructive pride in our lives. God exalts the humble, but he brings low the proud. Paul as usual gives a practical advice: “Don’t be proud, but be willing to make friends with people of low position” [Romans 12:16].

There is as well a hidden message in the parable that cries out for notice, that is, the tax collector reminds us that we should not give up praying because we have sinned. The Pharisee, apparently all good and proper and moving amongst the elites of the community, so we notice, prayed with great ease. The tax collector, on the other hand, prayed torturously, repentant and, standing far off, feeling unworthy.

This is where we believe the real difference between the prayers of the Pharisee and the tax collector lies. The tax collector is penitent; the Pharisee is judgmental. Does that not speak loudly to us as well? Are we not, in subtle and not so subtle ways, more judges than repentant sinners? Perhaps unconsciously, we all pray like the Pharisee, thanking God that we are not like so and so. But God knows what it is that we are so self-righteous about. Do not the daily news on the printed media and on the TV screen reflect the very pathologies and the violence in our own hearts? Truly, the miserable figure of the tax collector is told by the Lord for our instruction, that he might persuade us to give up on our self-assumed judgeship, admit to our sinning tendencies, bend our knees in repentance, and once again rely on his merits, his gratuitous grace.

That takes us to the particular point of the English translation of the Greek term used by Jesus to describe the tax collector’s plea which actually prompted this article. The original Greek bears a crucial reference to the work of Christ in salvation.

A Christological Reference

The Revised Standard Version’s English translation of the tax collector’s prayer is “God, be merciful to me a sinner!” The Greek expression “helasthēti moi”, used only here in Luke-Acts and in Hebrews 2:17, has the sense of “be propitiated to me” [see C.S. Evans, Saint Luke in the TPI New Testament series, p.644]. So, the tax collector’s prayer is more than just “God, have mercy on me”. It is a Christian or Christological prayer, if you will, for its distinct reference to the doctrine of atonement. When the prayer is “God, be propitiated towards me, a sinner,” there is more than a mere hint of atonement; it is a definitive acknowledgement of one’s unworthiness and inadequacy and a clear reliance on the sufficient atonement of Christ as the prayer is lifted to the mercy-seat of God.

In the New Testament Greek, “reconciliation” is worked out in two terms: katalagè [reconcilatio in Latin] and hilastèrion [propitatio in Latin]. Paul considers justification through faith. This justification of sinful humanity before God is accomplished by Jesus’ death on the cross. In choosing the Old Testament model of “propitiation”, Paul borrowed from the old cultic terminology. But, for it to work for Paul’s understanding, there has to be a shift in meaning. Cultic ritual of the sacrifice in the temple of Jerusalem at the annual Day of Penitence [Yom Kippur] involved the sprinkling of the blood of sacrificial animal on the cover of the Ark of the Covenant. The aim was purification and reconciliation to Yahweh. In the Synoptic Gospels, the celebration of the Last Supper pointed to Jesus’ death as atonement: “This is my blood, the blood of the new covenant, shed for many” (Mark 14:24). Included in this is the theological understanding of the idea of a substitute suffering and death. Jesus, as “the Man for others”, had led his disciples to interpret his death as a propitiation and his suffering as substitution. For Paul, whereas the cultic sprinkling of the blood sacrifice was only a preparation for the purification and consecration to be brought about by God, Jesus’ sacrifice of his own blood, in loving obedience, accomplished the reconciliation unconditionally. This entailed the unreserved acceptance by God, a truth that was attested by God raising Jesus from the dead on the third day. In Paul’s words:

- “And all are justified by God’s free grace alone, through his act of liberation in the person of Jesus Christ. For God designed him to be the means of expiating sin by his death, effective through faith.” [Romans 3:24-25a]

In telling the parable, therefore, Jesus already pointed forward to his suffering death as atonement and expiation for our sins.

Rather than being “confident of God’s mercy” or even puffed-up on account of one’s presumed righteousness, this parable teaches that whoever would approach God in prayer ought to plead the blood of Christ. Jesus in this parable teaches profound theology: there is no hope for the sinners but for the cross of Christ. Humanity deserved to die for crucifying Jesus on the cross. And yet, upon that very cross, God relented. By the cross of Christ, sinful humanity who could not justify themselves by their own presumed goodness, is justified. Now, the cross is the mercy-seat. So in the Jesus-prayer, we repeatedly appeal: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me the sinner.”

In his reflection on this parable, Charles Spurgeon, a highly influential 19th century Baptist preacher, had this most helpful remark in the context of our discussion:

- If thou wouldst find pardon, go to dark Gethsemane, and see thy Redeemer sweating blood in deep anguish. If thou wouldst have peace of conscience, go to Gabbatha, the pavement, and see thy Saviour’s back flooded with a stream of blood. If thou wouldst have the last best rest to thy conscience, go to Golgotha; see the murdered victim as he hangs upon the cross, with hands and feet and side all pierced, as every wound is gaping wide with misery extreme. There can be no hope for mercy apart from the victim offered – even Jesus Christ the Son of God. Oh, come; let us one and all approach the mercy-seat, and plead the blood.

Pleading the blood of Christ! The miserable tax collector in the parable did just that. He went home justified.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, November 2012. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.