And she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in bands of cloth, and laid him in a manger, because there was no place for them in the inn. [Luke 2:7, NRSV]

[L] “There is no room for him at the inn.” [M] Mother Teresa, from Time Photos. [R] The Good Samaritan.

“God lives on the margins.” Do you feel that in your guts? If you do, how will you give flesh to that intuition? And if we follow it right through, how will that intuition impact our Christian living?

We might begin by taking a step back and project on the screen of our mind, as it were, the big picture covering the front end, the middle section, and the tail end of Jesus’ earthly life. In his narrative on the nativity of Jesus, Luke declares that there was no room for Jesus at the inn.

- At birth, not only would there be “no room” for his family at the inn, Jesus the Emmanuel would be born in a manger. St Luke, from the outset, took pain to proclaim the fact that right from the inception of his earthly life, Jesus would join humanity at the margins of society, away from socially accepted regular comfort and decent neighbourhood.

- This sets the tone for what Jesus experienced during his ministry in reaching out to the nation of Israel. Rejected by people of his own hometown and seriously in loggerheads with the official religious leaders, Jesus “the Son of Man has no place to lay his head” [Luke 9:58]. In the Synagogue of Nazareth, Jesus, in the name of God, took a stand and defined his mission: to proclaim the Good News to the poor, to proclaim liberation to prisoners, to give back their sight to the blind, to restore liberty to the oppressed [Luke 4:24-30; quoting Isaiah 61:1-2]. In the face of his prophetic mission of inclusion, he was at once excluded, the people saying: “Is he not the son of Joseph?”

- And concerning Jesus’ death, the Letter to the Hebrews delivered to precision the message of the ultimate marginalization of Jesus: “For the bodies that are brought into the sanctuary by the high priest as a sacrifice are burned outside the camp. So Jesus also suffered outside the gate in order to sanctify the people through his own blood” [Hebrews 13:11-12].

And so, at his birth, during his public ministry and right through to his suffering and death, the whole story of Jesus witnesses to a severe marginalization by the official religious leaders and by what was considered to be “decent” society.

Such a revelation from Scriptures must bear serious consequences worthy of our attention.

- Evidently, contrary to popular belief, God does not have a residential address at the centre of power, or at the seats of the mighty and the powerful, or at the offices of those who claim to be holy. This is particularly true when those who use the privileges that come with might, power, and purported holiness to exclude and to push others to the margins.

Where, then, do we find God?

We propose a five-step reflection in attempting to answer that question.

1. From social observation, a disturbing reality

Wherever there is progress in human activities, as in scientific discoveries, technological advancement, industrial growth, economic independence, career ascent, financial success, or as in the popular Malaysian slogan “Malaysia boleh!”, God gets pushed further away from the centre of human existence to its periphery. In modern society, God is anywhere but at the centre of human existence 24/7.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer is absolutely right when he puts his fingers on the fact that only in areas of powerlessness, and in times of weakness, do we turn to God.

We have turned the Almighty Creator God into a God of the last resort, of minor miracles, a God who is like a neglected servant, a stop-gap God, a slot-machine [deus ex machina]. This God is still a deity, of course, but only a marginal one. We push God to the margins of human existence.

2. From ecclesial observation, a deep and painful reality about “Christians” and “Christian leaders”

We let two great figures in the Church tell us what they know as a fact about the reality in the Church.

First, in this Year of Faith, Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle of Manila calls the massive Filipino Catholic population “practical atheists”. The Philippines may proudly announce to the world that it is a Catholic nation. It is even true that Catholic churches are full to overflowing every Sunday. But, look at the lives that these Catholics live outside of the Mass, and you will be horrified by the absence of God, the Cardinal said. God is only for the one-hour of church service. The Philippino lay faithful are very practical in their daily living, and in their practicality, they live like there is no God, no divine commandments, no Gospel values to adhere to. In the way they live, therefore, Christians have consigned God to the margins.

Second, Richard Rohr, OFM, similarly applies the term “practical atheists” to a group of Catholics. But, in the case of this renowned Franciscan friar, who speaks from his vast experience in spiritual counseling, he is referring to a vast number of bishops, priests and religious. After having been in ministry for twenty or so years, these priests and religious have lost touch with the ground of all our being – God. They no longer believe in what they do. They have all but lost their faith, but they know not how to leave any more, for they know not where to go. So they stay on and do things which are quite meaningless to them. This is giving a whole new twist to the expression “going through the motion”. It is really sad, but the situation is much more pervasive than the official church cares to admit. From the privileged ecclesial observation of Richard Rohr, then, in the way they live, many church leaders have banished God to the margins.

3. In Scriptures, from Bethlehem to Calvary, the marginalization of the Son of God

“For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son,” the Evangelist John announces in 3:16a.

But this Son of God, who “became flesh and dwelt among us” [John 1:14a] was negatively judged by the world, disowned and banished to the margins of “decent” society, dragged to Calvary, and there crucified.

So Jesus suffered and died outside the gate [Hebrews 13:12a].

Towards the end, as the Gospel of Matthew narrates it, Jesus becomes explicit as he talks about his Second Coming. He identifies with those living on the margins:

- “as you did this to one of the least of these…, you did it to me” [Matthew 25:40].

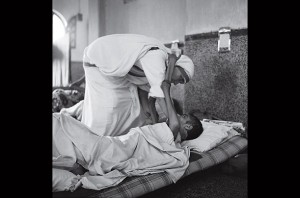

The Blessed Mother Teresa, who understood the depth of Jesus’ identification with the excluded and the marginalised, would respond to questions as to why she kept doing what she did day after day for the wretched poor, by raising a hand showing five fingers, saying:

- you

- did

- it

- to

- me .

“That’s why,” she said.

So Scriptures clearly point us to a God who resides on the margins. This God knows all about living on the margins. This God who has been marginalized, operates from the vantage point of the marginalized, to help and comfort those who suffer, and those who are made outsiders.

Now that we know where this God resides, the next question is what is the defining character of this God of the margins?

In lectio divina and in all our pastoral engagements, we must affirm and display the three central elements in the defining character of the God of the margins:

- First, a God of emotions [Bible stories are emotionally charged];

- Second, a God of passion [a suffering God, passionate in helping those who suffer]; and

- Third, a God of compassion [in solidarity, suffering with and in the people].

As Lent craws towards Holy Week, we remember with painful clarity how Jesus was first grievously tortured and then driven to the margins of the city to be crucified at the place of a skull [Golgotha]. Utterly marginalised, and feeling abandoned by friends and even by God, Jesus gives voice to his emotions. He laments on the cross:

- “At three o’clock, Jesus cried out in a loud voice, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?’

which is translated, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’” [Mark 15:34; Matthew 27:46]

He who was everything had everything taken away from Him. He who was perfect was totally misjudged as “sin” itself. All human solidarity and sympathy was taken away from him and he finally had to walk the journey alone, in darkness, in not-knowing. Hence he used Psalm 22:1 for his lamentation on the cross. How are we to understand Jesus’ troubling cry on the cross?

We must of course keep together two of the seven last words Jesus uttered on the cross:

- “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” and

- “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit”.

In the first word, what we see is Jesus embracing and befriending his brokenness and claiming it as his pain and his cross. In the second word, however, he also put his brokenness under the blessing of the Father. The key, then, to understanding Jesus’ Psalm 22:1 cry is twofold: Embrace your brokenness, and give it over to God.

We live in a world broken by injustices. Jesus is teaching us how not to cry in “Godless” despair. Having taken flesh and dwelt among us, Jesus’ lamentations are best understood as being in solidarity with those suffering from injustices. And then, even at his death, Jesus showed us how to trust the Father beyond the circumstances. In all this, Jesus is teaching us two valuable spiritual lessons from the cross:

- First, he is teaching everyone who is hurting that it is quite appropriate to lament when we suffer, so long as we seriously learn to finally give it over to God.

- Second, if you suffer much from an unfinished symphony in life due to an “unjust” situation, know that Jesus understands and is suffering with you. Go talk to him.

The point is, From Jesus’ cry on the cross, and many other gospel stories where those who suffer cry out to God for help, we see a piercing theme, that is, brokenness is at the heart of the Gospel story. From brokenness, people need help to move towards hope, to find hope, to live in hope, again.

In life, we too, have legitimate lamentations. Do we not long for someone to share our cross, sometimes? Do we not hope for a better tomorrow? Do we not want to move from lamentation to hope? God, who lives on the margins, knows. To the marginalised, God shows compassion.

Jesus, the incarnation of the Word, is the human face of God. The modality by which Jesus reveals God is through compassion – that which sparks hope. It was Jesus’ compassion for the brokenhearted and the rejected that drew women and men to Him.

Study the word “compassion” and we get to the heart of God. Why?

- Because every time you see the word compassion in the Gospel, a miracle took place.

- Because the singular and the defining character of God is compassion.

We turn now to some examples in Scriptures.

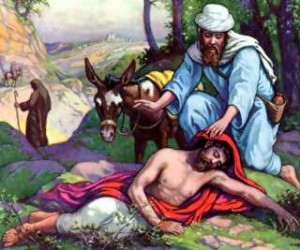

i. The Parable of the Good Samaritan [Luke 10:29-37]

A man is left beaten by robbers. A priest and a Levite pass by in fear that helping the wounded man will leave them ritually impure under the law. The Samaritan becomes the only person free to obey the higher law, to be a neighbour to the wounded, discarded and stranded – the severely marginalised.

Observe the Samaritan’s spirit of charity at work to create hope.

- The Samaritan man does not check the victim’s ID to see if he qualifies as neighbour; he becomes neighbour to him.

- The Samaritan man does not look into the beaten up man’s financial background, or does his calculations; he just settles the bills.

Concerning what the Samaritan does, the simple essence is:

- he sees;

- he has compassion;

- he helps.

He uses his own money, his own time, his own energy. That is charity at its best!

He just gets on with what needs to be done to help restore hope in a situation of pain and hopelessness.

He reminds us that talk is cheap. For hope, like love, needs to be more than a concept. It has to be concrete. Which teaches us that talk of “the love of God” is useless, unless it is something concrete that we can feel, that we can touch, that we can experience.

“Let us not love with words or speech but with actions and in truth” [1 John 3:18]. For that is the truth and essence of the Incarnation.

- “I love you” is not so much something you say as something you demonstrate.

- People bent low under the system, people who had their God-given dignity trampled on, need to be empowered in a concrete way to find the courage to live life with joy, to be enthused about life again.

In the tradition of the Eastern Church, Christ himself is portrayed as the good Samaritan. The badly wounded man lying beside the highway represents all of us – the wounded humanity. Christ did not pass us by in our hour of need. Instead, he was filled with compassion. He bound up our wounds and brought us home to the Father’s inn. This marvelous parable is talking about Christ himself. Anyone who takes the Good Samaritan for his example is imitating Christ.

We pause here for just a moment to look deeper into the word compassion and to appreciate its driving force.

[/to be continued in Part II in the next post.]

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, June 2013. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.