And she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in bands of cloth, and laid him in a manger, because there was no place for them in the inn. [Luke 2:7, NRSV]

[Continued from Part I]

[L] Healing of the Leper at Capernaum, by James Tissot.. [M] The Raising of Lazarus, by Caravaggio, 1608-09.. [R] Stained glass depicting Jesus Raising Son of Widow of Nian.

Understanding the driving force of Compassion [εσπλαγχνισθη].

Rather unfortunately, the original Greek term employed in the gospels – “esplagchnisthe” – is rather dully translated in different versions of the English Bible as “compassion”, “feeling sorry for”, “took pity on”, “his heart went out to” and so on. This is a classic case of something being inevitably lost in the translation. For esplagchnisthe is in fact a compound word which describes a gut-wrenching feeling: such deep empathy for the sufferers as to cause one’s internal organs to twist and churn, to be “internally terrorized”.

By using the word “esplagchnisthe”, the evangelists meant to say that, more than just a little concerned about people who suffer, Jesus was absolutely, utterly, internally moved by their plight.

ii. Healing the sick of the multitude [Matt 14:14]

Thus moved so deeply interiorly, Jesus, who needed quiet space to mourn the loss of John the Baptist and to commune with his Abba Father, stayed with the crowds who followed him on foot from across the lake, healing their sick and feeding the multitude through the miracle of the five loaves and two fish.

iii. Healing the Leper [Mark 1:41]

In Mark’s short narrative of the cleansing of a leper [Mark 1:40-45], the leper came to Jesus beseeching him, and kneeling said to him: “Lord, you can heal me if you want to.” Filled with compassion, Jesus reached out his hand and touched the man. “I want to,” he said. “Be clean.” There was no necessity for Jesus to touch the man. Even the centurion who had a sick servant at home knew that Jesus only needed to say the word, and his servant at home would be healed. But Jesus’ touch was acceptance, and sympathy by contact. Once again, a miracle followed Jesus’ compassion on one severely excluded by society on account of disease.

iv. The Raising of Lazarus [John 11:1-46]

In his narrative on Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead, the evangelist John employed three verbs to capture Jesus’ emotion and compassion as he encountered the sorrow-stricken sisters, Mary and Martha:

- Jesus was deeply moved in spirit [enebrimesato];

- Jesus was troubled [etarasen];

- Jesus wept at the tomb [edakrusen].

That Jesus broke down and wept only when they brought him to the tomb might be understood from our human setting in general. The tomb is the place of the last and definitive goodbye. Burial in the tomb marks the end of a person’s existence on the surface of the earth, and his transition to another realm. His or her story has come to a final conclusion; their presence, their company, their voices, their touch… are no more. Again, in the midst of Jesus’ deep solidarity with suffering humanity, he worked a miracle of raising Lazarus from the dead.

v. Raising the widow of Nain’s son [Luke 7:13]

And finally, we have selected the profoundly touching story of Jesus’ compassion towards the widow of Nain. When both of her men in the house, first her husband and now her son have died, this poor widow was left all alone to fend for herself. She would now be nameless, with no man to associate with, no one to relate to, and no one to depend on. Jesus’ heart went out in a special way to this woman left in the margins. What he said and what he did were extremely touching. He said to the widow, “Do not weep” [me klaie]. And he came and touched the bier, raised the dead man and gave him back to his mother. Again, he did not have to touch the bier. By doing it, he revealed God’s compassion through solidarity by contact and compassion in action.

These and other Gospel stories on Jesus’ compassion compel us to search for the sort of paradigmatic stories in a truthful faith community.

[5] Paradigmatic stories: moving towards a posture of compassion

What stories define us as a Christian community – the kind of community to which you would be proud to belong?

- Are we a faith community that marginalizes people, that excludes rather than includes?

- Or are we vehicles for the sacred and proactively become a community of disciples who include rather than exclude, who seek out, comfort and console those that suffer and are pushed to the margins?

- What kind of a paradigm most appropriately describes people like ourselves who are Christians, who profess to follow the Suffering Messiah?

Our answers must lie in stories of faith, not in doctrines.

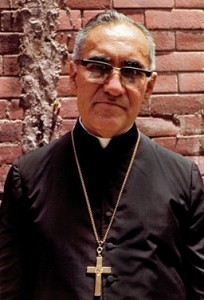

i. Becoming a voice for the voiceless

When Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador finally discovered his call at the margins, he realized that true mission was not in defending the powerful, but in advocating for the powerless. From then on, he became a voice for the voiceless, and lived courageously into his martyrdom. Assassinated on 24 March 1980 while celebrating Mass, he has inspired countless justice advocates worldwide.

ii. Discerning Jesus in the beggar

As Archbishop of Constantinople, St John Chrysostom (c. 347–407) has captured the essence of Jesus’ teaching in the last judgment discourse [Matthew 25] in these words:

- “Those who fail to recognize Christ in the beggar at the church door

will not find him in the chalice.”

This is also a strong echo of Paul’s teaching on “discerning the body” in 1 Corinthians 11.

iii. Serving the Lord in the poorest of the poor

The Blessed Mother Teresa of Calcutta has famously defined her work for the poorest of the poor in terms of serving the Lord in the poor. Her inspiration was captured in the five words uttered by the Lord:

- “You-did-it-to-me”

iii. Sitting at the same table with the excluded

Jean Vanier, founder of the L’Arche Day Break Communities, has a deep insight into what “inclusiveness” is. It is learning to sit at the same table with the excluded. In his practical philosophy, inclusion is “living with” rather than “doing for”. And all that is just doing what Jesus says, “I call you friends.”

iv. Honouring the image of God in the awfully rejected lepers

Dr Paul Brand [1914-2003] was an orthopedic surgeon and a true Christian, of whom Philip Yancey writes: “You need only meet one saint to believe.” His ministry was to “the least of these” – the lepers. “He knew first hand the awful rejection his patients experienced. His eyes would moisten and he would wipe away tears as he remembered their suffering. To him these, among the most neglected people on earth, were not nobodies, but people made in the image of God, and he devoted his life to try to honour that image.”

v. Touching the severely excluded

We can gasp in awe and admiration at the tactile approach [sympathy by contact] of Fr. Louis Gutheinz, S.J. towards the lepers. An accomplished scholar with a strong pastoral sense, he accepts the residents of lepers villages as friends, touching them, holding their hands, chatting and laughing, and sharing the same bottle of mineral water with them – you take one sip, I take one sip! When a religious sister who traveled with him tried, out of the goodness of her heart, to stop Fr Louis from such “outrageously” close contact that risked “contamination”, Fr Louis had to explain to her later that the key to this ministry that serves this highly sensitive and “excluded” sector of humanity is to truly accept them as friends. Otherwise, they sense your “rejection” all too easily and are wounded once again by you even in your “service” to them.

vi. Living the spirit of solidarity and compassion instead of blind obedience

Finally, we can be touched to tears by the spirit of a mother and the faith community who rallied to Sr. Louise Lears, S.C., and realise that God is truly present to the marginalised. In 2008, Sister Lears was forced out of all church ministerial roles by Saint Louis Archbishop Raymond Burke. The archbishop also placed her under a severe interdict, barring her from receiving any of the Sacraments within the archdiocese. Her “crime” was that she supported women’s ordination, even though she never sought or attempted to be ordained herself. This is an educated woman, with a Ph.D. in Medical Ethics. She believes in freedom of religion and freedom of thoughts and conscience, issues which the church preaches to and insists upon the outside world but does not appear to uphold in its own communal life. She is deeply committed to furthering the role of women in shaping the future of the Church but the official church vehemently refuses her to and excludes her from any serious discussions. Our Savior and his saints, we recall, won people over with love and understanding, not condemnation. The archbishop’s actions of exclusion and marginalisation had severely wounded Sr. Lears. Came Sunday, she desperately needed to be with her beloved parish community, to be present with this body of Christ, even though she had no intention of putting the parish in jeopardy by attempting to receive Holy Communion. But her 85-year old mother who was with her had other ideas. As her mother joined the communion queue, she told Louise to follow her. On receiving the Communion in her hands, the elderly mother broke it, turned around and gave a piece to her daughter and said to her, “I was the first person to feed you, and I will feed you now.” Isn’t that divine motherly love? After witnessing this, Sr. Lears’ sister went and did the same. And then, seeing what was going on, other parishioners, one by one, also broke their bread and gave a piece to her, so that by the end of communion, Louise’s hands were filled with fragments of the Eucharist.

This is a story that shakes you up, and forces you to rethink and reshape your theology. First, God is neither a lawyer nor legalistic. Second, when human agents sitting in positions of power and privilege abuse their positions by excluding and separating people from the love of God, causing them severe wounds and estrangement, the God of the margins who always includes and embraces the hurting will always find a way to be present to them. Third, we ought to recognise the margins as a holy place where God lives, where Jesus’ true face is shown and where God’s true power lies. There is possibility for immense grace living in the margins. Fourth, it often takes being on the margins for the laity to realize that God’s grace is working through them. It is when we reach out to the poor and the marginalized that we learn about the love of God, about what it means to live the Gospel of love, and about what makes a true church. And finally, the Eucharist, the body of Christ, will always rise out of the people, for the lay people have tremendous and extraordinary sacramental power which any old theology must acknowledge and adjust to. And consequently, it must dawn on us all that where the laity is, there is the church. And this is a statement of theological reality, even though it is not a statement of ecclesiastical legality.

And we would like to close with this quote from Sr. Joan Chittister, OSB :

- “The spirit that we have, not the things that we do, is what makes us important to the people around us.”

Amen.

[L] Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador. [M] Jean Vanier with John Smeltzer, a member of L’Arche Daybreak. [R] Fr Louis Gutheinz and a friend in a lepers village in China

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, July 2013. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.