When the chief priests and the officers saw him, they cried out, “Crucify him, crucify him!” Pilate said to them, “Take him yourselves and crucify him, for I find no crime in him.” [John 19:6, RSV]

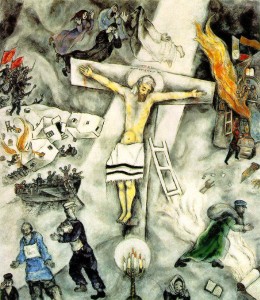

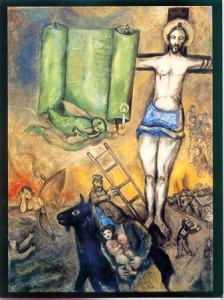

[L] The White Crucifixion, by Marc Chagall, 1938. [R] The Yellow Crucifixion, by Marc Chagall, 1943.

When the London Telegraph online edition of 14 March 2013 posted a piece titled “Pope Francis: Twenty Things You Didn’t Know About Him,” we scrolled down the list and stopped at the item that says Pope Francis’ favourite painting is Marc Chagall’s White Crucifixion. For years, this is a painting that has been of great interest to us.

1. Brief History

From the late nineteenth century onwards, Jewish artists have been portraying Jesus as a Jew. Their aim was to convey specific messages to both Christians and Jews. But it was not an isolated project, the whole trend being tied to the development of theological debates concerning Jesus’ origins. The modern study of Jesus’ Jewish background began in Christian theology in 1778, with the publication of The Aims of Jesus and his Disciples by Hermann Samuel Reimarus. As the study grew and developed within both Christian and Jewish scholarly circles in the nineteenth century, each group worked with different perspectives and aims.

- Christians wished to better understand Jesus within his historical and theological context.

- Over and above the context within which the Christians worked, the Jews had two other principal goals.

First, the Jews of the Emancipation, led by Moses Mendelssohn, were interested in building bridges between Judaism and Christianity. They did so by affirming Jesus’ positive qualities, as a Law-abiding Jew who was not interested in destroying Judaism, and spreading Jewish ideas among the pagans. Thus Jesus was portrayed as a Jewish teacher whose base was Judaism. By 1878, Jewish artists began giving flesh to this line of thinking, such as by portraying Jesus wearing a prayer shawl as he preached in the synagogue in Capernaum, or as a 12-year-old boy in the Temple surrounded by Jews dressed in a modern style. The aim of these artists was implicit: they hoped to help make peace between Jews and Christians.

Second, in stressing Jesus’ Judaism, they aimed to stem the rising tide of anti-Semitism throughout Europe and pogroms in Russia. From 1871 on, Jewish writers and artists tried to explain to Christians that in persecuting Jews they were attacking the brothers of their Christ rather than emulating his example of humility and charity. Works of art relative to this aim featured Jesus with Jewish facial features – a slightly hooked nose and side-curls – and depicting him in a skullcap and a costume that recalls a prayer shawl. Through these art works, Christians were warned that they had failed to abide by Jesus’ teachings, but were persecuting Jesus himself whenever they attacked Jews. Jesus, they reminded the Christians, would rise up against an aggressive Christianity as he once stood up against the Pharisees.

This is where many Jewish artists in the twentieth century found their inspiration. This use of Jewish symbolism climaxed in the period leading to World War II, when a group of Christian and Jewish artists took up this imagery and its message. Enters Marc Chagall.

2. The White and Yellow Crucifixions of Marc Chagall

Painted in 1938, The White Crucifixion is the first of several works in which Chagall visualizes the Crucified Jew. It is currently housed in the Art Institute of Chicago.

The focal point at the centre of the picture is Jesus nailed to the cross wearing a head-cloth and a loincloth made from a Jewish prayer shawl (tallit). The whole painting is set against a snow-white colour, while Jesus is lit with a yet whiter broad stream of light from above, obviously signifying illumination and affirmation “from on high”, and by a menorah from below, signifying his Jewish roots during his earthly journey. He is mourned by the Jewish patriarchs and a matriarch, and surrounded by scenes of pogroms which feature Jews attempting to flee as Nazis destroy villages, loot and burn their Torah Ark and sacred scrolls. In the upper left, the Russian army approaches flying red flags, signifying invasion and wanton destruction of Jewish communities.

There are commentators who are quick to suggest that Chagall painted this picture as a mockery of Christians and their Christ, implying that it is strangely ironical that Pope Francis as head of the Catholic Church should make the colossal mistake of liking this painting. That, however, is to seriously miss the point the artist himself had for his work. To be sure, Chagall’s work is at first sight quite startling, in that Jesus’ crucifixion had hitherto been seen, at least by Christians, as a symbol of oppression by the Jewish people against Jesus. How could Chagall, himself a Jew, make use of Jesus’ crucifixion to tell his Jewish narrative of oppression by others against the Jews? On reflection, however, it makes perfect sense. Jesus’ cross is a symbol of atrocious human cruelty against an innocent human being, and could be embraced and used as a symbol of the immense Jewish suffering as well. For that matter, Jesus’ suffering death may be co-opted by artists to symbolise universal human suffering. We recall reading many years back about an Australian artist, a professed atheist, who was stunned by the fact that every time he sat down in an attempt to draw a fitting symbol of human suffering, he struggled fruitlessly and eventually ended up painting a cross. He would throw that into the dustbin and try again. But, after agonising intervals, he always ended up drawing a cross. In the end, he was shocked to discover that he had a dustbin full of discarded symbols of the cross! Indeed, in 1977, Chagall explained the symbolism of his wartime pictures in these terms:

- “For me, Christ has always symbolized the true type of the Jewish martyr. That is how I understood him in 1908 when I used this figure for the first time…It was under the influence of the pogroms. Then I painted and drew him in pictures about ghettos, surrounded by Jewish troubles, by Jewish mothers, running terrified with little children in their arms.”

In 1943, Chagall took this symbolism even further in the Yellow Crucifixion: Jesus is crucified wearing his prayer shawl-loincloth and phylacteries (tefillin) donned by Orthodox Jews for their morning prayers. The second hint of Jesus’ Jewish roots is scored by letting an off-center figure of the crucified Jesus share the central space of the picture with a large depiction of an open Torah scroll. There, Jesus’ right arm appears to be joined to the Torah. He is surrounded by suffering refugees and persecuted Jews who had tried to escape Germany aboard the Sturma, drowning when no country would entertain asylum or allow disembarkation, for fear of reprisal by Hitler. In the lower right corner of the picture, burning buildings and figures in postures of agony complete Chagall’s portrayal of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust in his native eastern Europe. A fleeing woman with her child is reminiscent of the story of Jesus’ flight to Egypt as a child, further linking the persecution of Jesus’ family with the persecuted Jewish people.

Clearly, Chagall has attempted to express the horror of the Holocaust by using the image of the crucified Christ in combination with overtly Jewish symbols. In so linking Jesus to the fate of the Jewish victims of Hitler, Chagall had used the most powerful image of suffering in the Christian iconographic tradition to confront viewers with the cruelties being inflicted on Jesus’ people. Concerning the crucifixion as a basic motif in Chagall’s work, we really ought to let him tell the world what he wanted to portray. This was what he had himself unambiguously defined:

- “My Christ, as I depict him, is always the type of the Jewish martyr, in pogroms and in our other troubles, and not otherwise.”

3. Pope Francis

Pope Francis, who so clearly is a man who sides with the poor, the suffering and the marginalized, not to mention the religiously persecuted and martyred, must surely love the White Crucifixion of Marc Chagall precisely on account of our Christian understanding of Christ as the Innocent One crucified on account of human sins. Christian theology that teaches the solidarity of the Suffering Messiah with the suffering humanity finds a perfect emphasis in the common suffering of Jesus and the Jewish people in Chagall’s art. Pope Francis is not one who forgets the Jewish roots of Jesus. His solidarity with the poor brings him spiritually close to the Jews who suffered in the hands of the Nazis. And yet, above all else, what appeals to Pope Francis is the sign of hope. The Paschal Mystery which stands at the centre of the Christian narrative, is a journey from pain to hope, from darkness to light, from death to new life. Always mindful of the reality of human cruelty and suffering, Christian theology is nothing if not a theology of the cross and a theology of hope. For Pope Francis, the scene in The White Crucifixion:

- “isn’t cruel, rather it’s full of hope. It shows pain full of serenity. I think it’s one of the most beautiful things Chagall ever painted.”

[Quoted by Carol Glatz in Catholic News Service website, April 3, 2013.]

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, May 2013. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.