See, this alone I found, that God made human beings straightforward, but they have devised many schemes. [Ecclesiastes 7:29]

The rolling hills of Rwanda

Truth be told, we set off for Rwanda feeling a surge of anxiety. From the media, this would be a highly unsafe travel destination. It is, after all, a land most known for genocide in recent history. Did not a couple pull out of the group after signing up earlier, purely on account of security risks? In any case, if, as tourists or pilgrims, we were confronted with the poverty of facilities in Uganda on account of poor economic development, what had we gotten ourselves into now by coming to Rwanda, ravaged as it must have been by tribal strife as the media had abundantly reported?

At the beginning of the trip, Fr Emmanuel had “warned” about two things. First, the Belgian colonizers had left their legacy in administrative efficiency characterized by rubber-stamps and procedures. Second, we would be surprised by some sharp contrasts when we reached Rwanda, but he did not elaborate, so kindly leaving us to savour the surprises. We learned the accuracy of the first warning soon enough, as we were kept at Gatuna immigration check point for two hours, even though we all had the visa approved online as a compulsory procedure long before we left home. When, at the end of a long day on the road, similar delays occurred at the hotel counter in Kigali, some of us just blew our tops. Sarcastically, we said, the locks on our bedroom doors would not open until all our passports had been photocopied and stamped!

The second surprise was quite something else. For us Malaysians, the closest analogy we could think of to describe the surprise Fr Emmanuel alluded to is the experience of a marvellous “difference” whenever we cross the causeway from Johor Bahru into Singapore. Suddenly, the roads on the Rwandan side are well paved and immaculately clean, the road curbs nicely painted, and well manicured landscapes aesthetically road-divide the dual carriageways. Kigali city centre runs in a surprisingly orderly fashion, with well-painted zebra lines and operating traffic lights. The whole place is sparkling clean, and seriously contradicts what we had in mind of a badly deprived third world country. People were well-dressed, law-abiding and friendly. We certainly felt a lot safer walking on the streets of Kigali than in our own federal capital, Kuala Lumpur. Before we realized it, all our residual fear of a possible troubled and unsafe destination had evaporated. We felt totally relaxed and peaceful throughout the few days that we were in the country. So all that media bias about Rwanda being an unsafe tourist destination is, truly, all it is – media bias. And all those governmental travel advisories, especially in the West, are just hogwash. We became conscious of how much more exposed to danger we often are in cities in the West like London or New York, Amsterdam or Brussels, and in the big cities of China where the crooks could probably steal the milk from the tea you are drinking. It is so easy and so ludicrous for “civilized” people to suggest that it is safer to travel amongst people in suits and ties in developed nations than to be amongst the simple peoples of the less developed destinations.

Rwanda eschews the use of plastic bags and that alone contributes in a big way to the amazing cleanliness of all places of public access. Furthermore, we were soon pleasantly surprised by a national discipline, albeit government-sanctioned. On every last Saturday of the month, all citizens are expected to commit to community service, known locally as “Umuganda”, to keep the country clean. It soon dawned on us that such amazing cleanliness and orderliness everywhere we visited could not be attributed solely to a government mandate; a habit, a culture, of cleanliness has evidently become a priority of the Rwandans themselves. To top it all, Rwanda is a seriously beautiful country, giving substance to its reference as a land of a thousand hills.

And yet, the picture is also somehow seriously dissonant. In sharp disharmony to all this scenic beauty, clean city and well-behaved citizens, Rwanda is a seriously blood-stained nation, marked as it is by its recent history of a blood-chilling genocide. Genocide, in essence, is the attempt by one race to wipe out another race which the perpetrators consider unfit to live. How anybody could make such a judgment is a question that has to do with the deepest realm of evil in the world. Truly, anybody who did a minimal research on the topic would be horrified by the stories and the statistics. Over a period of 100 days in 1994, a million people were murdered in a complex “tribal” killing. We cannot recommend strongly enough a brilliant book in this field by Fr Emmanuel Katongole entitled Mirror to the Church: Resurrecting Faith after Genocide in Rwanda. There, readers will find an immensely rich and deep reflection on the root causes of the genocide, and the way forward in a truly Christian resurrection faith.

Constrained by time limitation, our itinerary was necessarily selective. Still, our visits to three memorial sites convinced us that evil knows no bounds.

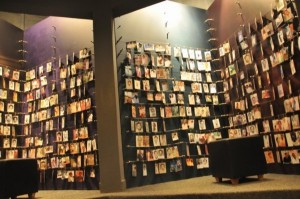

1. The Kigali Memorial Centre

The Kigali genocide Memorial Centre is a must for first time tourists. But it promises to be more than of mere tourist interest. Located in Gisozi, this Memorial is brilliantly conceived and documented, but it can also be deeply affecting. More than a place of memory, it represents a call to regret, to lament, to action. On site are archival exhibits, gardens, burial grounds, and the Wall of Names memorial. One needs a minimum of an hour and a half to see the full exhibit. It is well worth scheduling two hours for this place on one’s itinerary, to read, to see and to watch.

The Centre’s official website briefly describes itself:

- The Kigali Memorial Centre was opened on the 10th Anniversary of the Rwandan Genocide, in April 2004. The Centre is built on a site where over 250,000 people are buried. These graves are a clear reminder of the cost of ignorance. The Centre is a permanent memorial to those who fell victim to the genocide and serves as a place for people to grieve those they lost…One of the principal reasons for the Centre’s existence is to provide educational facilities. These are for a younger generation of Rwandan children some of whom may not remember the genocide, but whose lives are profoundly affected by it.

While this centre is affecting, it did not remotely prepare us for the emotionally draining visits we made to the next two sites.

2. The Nyamata Genocide Memorial Church

Nyamata church entrance and interior

Doubling as guide, the official caretaker of the Nyamata Catholic Church showed us the original iron gate at the church entrance. Their entry thwarted by a padlocked gate while thousands of people were hiding inside, the Hutu militia and their Interahamwe blew it open with grenades, went in, and executed their mad killing spree.

Upon entering the Nyamata Church, our whole being was just absorbed into an indescribable, aching spiritual solidarity with the victims, all killed in the Church, some by gun shots but mainly by machete. So deeply were we affected by the victims’ blood-stained clothes, arranged pile after pile, and row after row on wooden pews, that our tears just rolled down our cheeks. We could not stop them even if we wanted to. Overwhelmed with grief, we walked slowly for a while, in horrified silence, each thinking our own thoughts, each spontaneously loving the poor innocent souls and respecting their God-given dignity in ways that escaped words. Here is a very poignant memorial indeed, and these clothes humanize the events and atrocities of the genocide. From deep within our souls, all we could do was cry in mournful refrain: “Why, oh why, Lord?” “Lord, keep these innocent victims close to your bosom!” “Lord, have mercy on us all!” ….

The guide pointed to the altar, the stained altar cloth, some machetes and an identity card on display. Children, too short and inconvenient for killing by machetes, were lifted onto the altar for easier slaughter. We were appalled beyond words. Right there, Matthew’s report on the “massacre of the innocents” together with his understanding of the Old Testament prophetic fulfillment [Mt 2:16-18; Jeremiah 31:15], and John’s iconic image of Jesus Christ as the innocent “Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” [John 1:29] were words of the living God that breathed new life into modern day stories of the deranged slaughter of innocents.

Desecrated and broken into, the Tabernacle was not spared. The stand on which it stood was riddled with bullets.

Hutu militia massacred some 6,000 people in this church. The victims’ only crime was that they had been labeled a Tutsi on their identity card. The sanctuary was ruthlessly violated. A place reserved for God’s residence and shelter for His people was senselessly desecrated. There was no respect for human lives, no morals whatsoever, not even the basic fear of God. Evil knew no bounds. Evil took what was not its to take. Adam’s fall continued its devastating influence. The sacred authors took to narrating the cycles of violence in the Bible, beginning from the time Cain killed Abel. Once killing began, a human being has turned into a savage. Levity followed, buoyed by arrogance and presumptions without morals. Cain’s cavalier dismissal of God’s serious question says it all: “Am I my brother’s keeper?” [Genesis 4:9]. And as Mary McCarthy puts it succinctly, “In violence we forget who we are.” And if we forget who we are, is it not because we first forget who God is?

In a way reminiscent of the Nazi Holocaust, the modus operandi was chillingly inhuman. First, a decision was reached in which the Tutsis were identified as being unfit to live. That decision was then secretly but efficiently communicated down a chain of command which, in obedience, accepted without question the decision as legitimate and good. Then the Tutsis were systematically rounded up into a concentrated location, in this case a church. And there, they were exterminated. It was insane.

We recall, too, the political theorist Hannah Arendt who, reporting for The New Yorker on the trial of high-ranking Nazi Adolf Eichmann, coined the phrase the “banality of evil” to explain evil occurring when ordinary individuals are put into corrupt situations that encourage their conformity.

Even the statue of Our Lady, installed on a high platform, suffered a chipped left shoulder and her garments soiled by blood splatters. What pain all this must have caused Our Heavenly Mother, watching her children turned into animals slaughtering their brothers and sisters?

In the basement of the church, twelve steps down, are open tombs with thousands of skulls and bones, many of children.

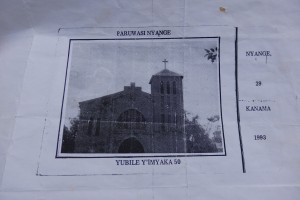

3. The Memorial Site at Nyange

The church at Nyange, [L] before genocide, [R] today.

If Nyamata was horrifying, nothing prepared us for the demoralizing horror and pain at another mass killing site, Nyange. Before you continue reading this post, we recommend that you first read the report and reflection titled “‘God is Innocent’: Rwamasirabo on the Genocide in the Church at Nyange, Rwanda” by Chris Heuertz, an immensely gifted pilgrim from America with whom we were privileged to travel, at this link – http://www.redletterchristians.org/god-is-innocent-rwamasirabo-on-the-genocide-in-the-church-at-nyange-rwanda/ .

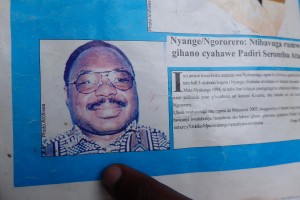

[L] The notorious convict, Father Athanase Seromba. [R] Mr. Rwamasirabo in his little office cum museum, located where the sacristy was in the former church.

A priest, Athanase Seromba, whom we imagine would regularly claim to act in persona Christi, was in reality a devil-incarnate, who planned and executed the murder of a few thousand parishioners. Collaborating with the Hutu militia and the Interahamwe, Seromba gave the order for the church of which he was pastor to be bulldozed on 6 April 1994, while it was filled with parishioners hiding from the massacre. He personally shot some survivors as well. Fleeing Rwanda in July 1994, he later moved to Italy and continued working as a priest at a church near Florence. Arrested and tried by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), he was found guilty of crimes against humanity committed in the Rwandan genocide and sentenced on 13 December 2006 to 15 years in prison. Upon his appeal, the Appeals Chamber of the ICTR on 12 March 2008 affirmed his conviction, and increased his sentence to life imprisonment. He is serving his life sentence at Akpro-Missérété prison at Porto-Novo, Benin.

Three Lessons from Mr. Rwamasirabo

Nyange was deeply disturbing for us not only because the completely bare ground of the former church shocked our imagination, but because our hearts were troubled by our encounter with Mr. Rwamasirabo, the official guardian of the memorial church. In him we saw the human face of all the victims and their families, a face that would haunt our memory for a long time to come. His entire family, and a few thousand victims, had died at the hands of the notoriously evil priest.

When the Interahamwe came, armed with a list of names of local residents, first on the target was Rwamasirabo – a businessman, the only person in the village with a car, and thus a village-level leader. He had to go into hiding in the jungle, leaving his wife and children in the supposed safety of the church. In the genocide, he lost his entire family and his means of livelihood. He is now all alone, his deep wounds clearly unresolved. Bitterness, understandably, accompanies his daily existence. We respected his life journey, and whatever stage of healing he might be at. But, utterly stunned by his story and out of sheer love and concern for him, the pilgrims raised a few almost “silly” questions. In the process, we learnt some powerful lessons from him about our faith.

[a] “God didn’t do this”

“Do you still believe in God?” we asked.

“Of course, I believe in God,” he answered.

“But how can you still believe in God? Are you not angry with God?”

“No, I’m not angry with God because God didn’t do this. Evil human beings did all this. Evil human beings killed my family and my friends, not God.”

In the depth of unimaginable suffering, this man knows that God is innocent! The biblical story of Job rang in our ears.

In that branch of theology known as Christology, it is immensely useful to turn to René Girard for his understanding of mimetic violence and the scapegoat mechanism. Apart from yielding a model for understanding Jesus’ death on the cross as a model of non-violence, his theory is immensely helpful for [a] restoring the image of God as loving, merciful, forgiving and non-violent, [b] facing up to the truth and ugliness of human violence in the death of Jesus, and [c] understanding the way for Christians.

- Jesus on the cross was the wholly innocent one.

- Jesus on the cross exposed the violence of the killers.

- Sinful humans put Jesus on the cross; God “didn’t do this”.

- God did not demand the death of his Son.

- God did not will and plan the death of his Son.

- On the cross, God exonerated the innocence of the scapegoat.

- “Scapegoats” cannot carry the guilt of the killers; it is not right to use scapegoats for vicarious sacrifices.

- On the cross, God refused to return violence with violence.

- On the cross, God met violence with love and forgiveness.

- On the cross, God did not kill his Son, but humanity killed the God of sacrificial love and peace.

[b] Faith vs. Religion

“Do you still go to church?” we asked.

He answered: “No, I have stopped going to church. I believe in God, but I don’t believe in the Church anymore. The evil priest of the church killed my family. I will never trust the priests again; I never want to have anything to do with the church again. And I will never forgive them for what they have done.”

“But do you still pray?”

“Of course, I pray. I pray to God. I don’t need to go to church to do that.” His spontaneous “of course” powerfully affirmed St Augustine’s insight of the heart’s deep yearning for God. In this plain man’s prayer, we saw an image of faith that is completely natural to the human heart. Confronted so rudely by our inherent fragility and mortality, and staring into the existential void without shrinking away, the heart becomes aware of a deep spiritual need that points to the Transcendent Other, the Creator, the Lord who gives life and who never abandons us. There is a natural human aspiration towards this transcendent divinity for solace and for the ultimate and enduring meaning of life. Praying to this transcendent God, who through the Spirit of Christ has become so immanent to us at the same time, is our deepest human longing.

But, in Mr. Rwamasirabo, we also saw an unarticulated comprehension of a clear difference between faith and religion.

- The one pertains to substance; the other, as clearly as we have eyes to see, is perpetually at risk of bending its knees before systems and structures, doctrines and canon laws, insisting on blind obedience to men rather than God, and wrapping its arms around the altar of attractive but empty forms.

- The one has a depth understanding of Jesus’ primary goal in creating a community of love committed to the work of Kingdom-advancement; the other, history and now Pope Francis tell us, is perpetually caught up in self-referential activities and exclusionary measures in power-manoeuvring.

- The one knows ultimately who is the Creator of the universe, sustaining it and giving it life; the other, adherents of the religion know only too well, are wont to ride roughshod over your baptismal dignity, crowing mightily on a dung heap, as the late venerable Fr. Bernard Häring put it: “We are the ones to decide!”

Continuing, Mr. Rwamasirabo said, “After the genocide, a new priest came and wanted to build a new church on the exact same spot as the old one that was bulldozed. The people angrily refused because that would allow them to erase the evil that was committed by the priest and the militia. We must keep this place as a memorial to so many people murdered in it.”

[c] From a Place of Despair to a Place of Hope

Our encounter with Mr. Rwamasirabo brought forth another troubling reality in the human paradox. In a way, it is the Garden of Eden all over again where Adam and Eve were right after the fall. Scriptures say poetically that, in the cool of the evening God was walking by, but they hid from Him. They were hiding from the God who gave them life, who could heal and save them, because they felt guilty and were afraid. Mr. Rwamasirabo, though clearly not guilty, was afraid nevertheless. He is all alone in this world, his entire family having been annihilated. He needed to be faithful to his family. He needed to be strong. He must not forgive. He must hold fast to their memory. He must not forget who did this ultimate evil to them. So he kept aloof. He hid from God-in-the-faith-community and continues to hide from Him, the One who could heal and save him. That is the only way he knows to stay sane, and to stay faithful to the memory of his family. And he thereby holds himself hostage in the prison of hate that he had himself erected, denying himself of the opportunity of reconciliation and peace.

And so, as much as we appreciated Mr. Rwamasirabo’s sentiment and respected his tormented journey in life, we knew that he needed, as we all do whenever we find ourselves in crisis patches, to move beyond his gross disappointment and deep lamentation to a place of hope. As this post appears in the second half of December, our minds naturally turn to Advent – the coming of the Christ, the Saviour of the world.

- He came to inaugurate the Kingdom of God, that the rule of God may be a reality “on earth as it is in heaven”. By his birth, He brings hope for humanity – hope of pardon, hope of peace with God, hope of a future glory that awaits us with God. As Word of God made flesh, He dwelt amongst us in a world of fear and doubt, violence and suffering.

- As the Lamb who “took away the sin of the world”, He gave himself to us totally, and humanity chose to kill him. So his Birth is linked to his Cross – a combined guarantee that God is not fooling in his love for us, but is part of the reality of our fragile human lives. Christmas joy at its best is a celebration of God’s incredible love for us, to the point that He personally took all the consequences of being one of us, of being love in a world not very good at loving.

- He came in poverty and humility, to interrupt the violence – sin, evil and death – in fallen human condition. He came to show death-bound humanity the way to transform death to new life. He came to show us that it is feasible to live God’s Kingdom-values, away from violence, all the way to the cross. His journey of interruption for the sake of humanity would cost him dearly, but he would be obedient, not to men, but to God, till death if necessary, so that sinful humanity might live better and treat each other with a little more grace. His work of interruption aimed to promote a transformation of human relationship.

To stories of hope through interruption to the great evil in the Rwandan genocide we shall turn in a coming post.

We wish you all a season of joy and peace that flows into the New Year.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, December 2013. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.