And Jesus said, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do.” And they cast lots to divide his garments.[Luke 23:34, RSV]

[L] John the Baptist, in Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment fresco, Sistine Chapel. [R] St John the Baptist in the Prison, by Juan Fernandez de Navarrete, 1565-1570.

Imagine that you are sitting in a theatre. Directing the play is Mark the Evangelist. For the opening scene, he grabs your attention with a shrill narrow-tubed war trumpet sound. As the curtain slowly rises with this clarion call, he confronts you with the sudden appearance of a name-calling wild man – wearing camel skin, eating locusts and drinking wild honey. Standing smack at the front of the stage, he points menacingly right at you, screaming: “Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight” [Mark 1:3]. You feel sinful, you feel guilty, and you certainly feel that you have fallen short in discipleship.

Driven by a sense of urgency, the Evangelist Mark wrote impatiently. Neither an infancy narrative nor a genealogy, which Matthew and Luke took time to elaborate, appears anywhere in the Gospel According to Mark. But what is absent in Mark’s narrative, he more than makes up for with a stunning entrance for an opening scene. He compels the readers to sit up and stare wide-eyed at this prophetic figure – John the Baptist – crying in the wilderness, announcing the nearness of the kingdom of God, demanding that we change our ways, shape up, and respond appropriately to the coming Lord who is inaugurating the new kingdom. The Baptist has absolutely no question in his mind, no doubt in his heart, and no hesitation in his words. He entertains no excuses and takes no explanations. He wants action, and he wants them now. He is nothing but confident, certain, and table-slapping demanding. This “immediacy” in Mark’s narrative starts from the get-go and runs right through his Gospel to the very end [which in the original draft-script featured the death of Jesus and the bewilderment of the followers and their dispersal in verse 16:8].

It isn’t until chapter 3 in their respective Gospels, that we find Matthew and Luke narrating the same Baptist-episode. By then, the sense of immediacy is lost. The rough and offensive demand of the Baptist does not burn as caustically. What they lack in causticity and searing urgency, however, they more than make up for by transposing our attention to a more ponderous Baptist in prison. By now, the Baptist has mellowed from a fiery preacher to a searching enquirer. He neither proclaims nor demands. As the wilderness expanse gives way to the restricted confines of a prison cell, he no longer resorts to name-calling anymore. The prophet with a menacing voice is now a prisoner with a penetrating question. “Are you the one who is to come, or shall we look for another?” [Matthew 11:3].

What happened to cause that change?

In prison, one has time in surfeit. Prisons may soften one up, and lead one to deeper contemplation. Far from any negative connotations, this “softening” is often holy ground where grace works its mysterious wonders beyond our human calculations. For surfeit time combined with restricted movement open the doors for the spiritually inclined to dive deep in contemplation, to seek the essentials rather than the superficial, to hear the soft whispers of God. Recall the youthful and impetuous Moses up on the mundane, monotonous, and yet holy ground of Mount Sinai. YHWH used a second cycle of forty years in his life to slowly “soften” him up, before dispatching him on a holy mission of setting His people free from slavery, indignity and injustice. The stories of Moses and John the Baptist point to a consoling lesson. Where others see one’s future eclipsed and potentials seriously curtailed in physical confinement, God may in fact have other ideas. This period of restrictions may turn out to be a time when one is blessed with a deeper appreciation of God’s vision for His people. In a time like this, the essence of life given by God, in clear distinction from the clamorous incidentals, may come into sharper focus.

This is what we see in Dietrich Bonhoeffer whose singular focus during his time in prison was the issue of Christian essence. Incarcerated by the Nazis at Tegel prison, he wrote:

-

“What is bothering me incessantly is the question what Christianity really is, or indeed who Christ really is, for us today.”

To similar effect, we see this reflected in Paul’s prison letters as well. Take his Letter to Philemon for instance. There, Paul the fiery preacher, quite aware of the essence of Christian love, forgiveness and fraternity, avoids making demands and resorts instead to making a plea, all for the sake of persuading a friend to accept a runaway slave as a person of equal dignity and worth, and a brother in Christ.

- … though I am bold enough in Christ to command you to do your duty, yet I would rather appeal to you on the basis of love – and I, Paul, do this as an old man, and now also as a prisoner of Christ Jesus. I am appealing to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I have become during my imprisonment. Formerly he was useless to you, but now he is indeed useful both to you and to me. I am sending him, that is, my own heart, back to you … that you might have him back forever, no longer as a slave but more than a slave, a beloved brother–especially to me but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord … [Philemon 8-14].

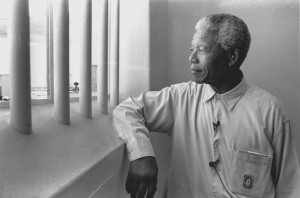

We recount all this, to make the link to that contemporary giant figure on the world stage – Mr. Nelson Mandela – a universally respected charismatic figure whose recent passing was both dearly mourned and gratefully celebrated throughout the world.

Presiding over the Justice and Peace Mass in honour of Mandela December 13, 2013 at the Notre Dame Sacred Heart Basilica, USA, Fr. Emmanuel Katongole’s rhetorical opening questions included the following:

- How does one who spent twenty seven years of brutal imprisonment, emerge from that jail with one of the most endearing and genuine smiles the world has seen?

- How can a man whose hands were chained and enslaved by the cruelty of apartheid, emerge from jail with arms outstretched in a forgiving embrace of the enemy?

- How can one who suffered the most debasing and dehumanizing cruelties and injustices, forgive his jailers?

- How can one deprived of his freedom for so many years turn out to be one of the most free persons?

The answers hidden in all these questions pack a powerful message for leadership and Christian living which we call the Mandela-factor. The key lies in freedom from a spiritual prison that demands dignity and respect for oneself, however much one deserves it, without according respect and dignity to others. It is grounded in the recognition of fundamental human dignity and equality for all, beyond one’s egotistic needs and the “tribal” interests of one’s group within a larger community.

Ironically, the physical prison provided the conditions of possibility for Mandela to be set free from his inner prison of hatred and vengeance, and from the Baptist’s causticity and scathing urgency. In prison, he had time aplenty to search and find that true freedom in God. And the whole world is grateful to God for that immense gift of freedom Mandela brought with him as he exited the prison. That most arresting Mandela-smile for which the whole world was blessed to see, was a symbol of a true inner freedom – an outer sign of an inner grace.

Nelson Mandela’s incarceration for twenty-seven years on Robben Island was as unjust and outrageous as it ever gets anywhere in the civilized world. And yet, grace worked its mysterious marvels precisely in those outrageously unjust prison years for Mandela, and for the world really, given the potentially huge impact Mandela’s life-witness has for humanity. Mandela, who had every right to be indignant in the face of the evil of apartheid, was saved from participation in the bloodshed and the violence raging in the South African society during the time. Had he not been held in captivity, even if he and his fellow freedom-fighters had toppled the apartheid regime, the victory would in all probability have been won through a violent armed-struggle. Peace, in such a scenario, would be a dream more than a reality. What ensued from a violent victory would have been endless cycles of violence and an absence of any real peace.

By contrast to that alternative scenario, with time in his hands while incarcerated, Mandela slowed down and started dialoguing even with his “enemies”, beginning with the prison staff, at a simple, human, and friendly level. He would gain a depth-insight into the universality of all things human. He would discover:

- that “they”, too, have their weaknesses, their worries, and their fears;

- that “they”, too, have human needs and concerns;

- that “they”, too, are entitled to have their basic needs respected, and their security concerns allayed; and

- that people cannot listen, unless their basic needs and concerns are met.

In a way that was truly incredible, the prison had set Mandela free to be authentically human, as a child of God. It takes a truly free spirit to live in true humanity and co-humanity. One has to be truly free inside to live in freedom and solidarity. The power of that inner freedom would pave the way for his nation-saving and nation-building work of forgiveness and reconciliation, justice and peace.

He left prison convinced that there could be no lasting political solution if the “enemies” were left with the stark binary alternatives of either fight to the death for self-protection or risk losing everything they had ever owned and worked all their lives for. Instead, he would come to the insight that any long term solution for a lasting and equitable political settlement in South Africa must include a promise of security and protection for the White South Africans as well. You cannot rid society of discrimination by reverse discrimination. You cannot achieve peace while you entertain vengeance. You cannot have peace, unless you accord peace. There could be no lasting peace, and no prosperity for all South Africans, without forgiveness, peace and reconciliation. The words and spirit of Martin Luther King, Jr., at his famous address to the mammoth crowd on civil rights march on Washington on Wednesday August 28, 1963 had rubbed on Mandela:

- In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds… We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline.

To achieve what needed to be achieved, to be a true statesman not just for the Black people of South Africa but for those who had hitherto been operating the apartheid regime as well, Mandela embraced the wisdom that he must first be saved from the self-defeating prison of hatred and vengeance. He succeeded. But it was, in his own words, “a long walk to freedom”. Ultimately, it was a long walk to truly embrace the Beatitudes in Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount.

- Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. [Matthew 5:9-10, NRSV]

Freedom, however, is as much a task as it is a gift. The central theme and non-negotiable point of departure in Mandela’s legacy is his steadfast commitment to human dignity. From that starting point, Mandela rose above ideology, as he upheld the fundamental principles of non-racialism and the intrinsic equality of every person. Far from a call simply to slogans, platitudes or ideological rigidity, this legacy prods us on to a sincere examination of ourselves and our relationships at both the personal and communal contexts. Grounded in a conciliatory spirit, his work for the common good yields the basis for honest and sincere discussion and debate in all sectors of human activities – family life, communal welfare, governmental policy-making. His vision encompasses everyone as being called to freely use our liberty to create a better society through our everyday actions. Upon being sworn in as President of South Africa in 1994, Nelson Mandela said these famous words:

- Let freedom reign. The sun never set on so glorious a human achievement.

People around the world recognize true goodness when they see it. In a world of strife and darkness, Nelson Mandela is recognized as a guiding light. His was a life of struggle, courage and hope. Despite extreme hardship and lengthy incarceration, he never waived his fight against apartheid. Even more, the humility of the man, when the world was under his feet, must humble us all. Walking away from power and authority, refusing to seek a second term in the Presidential Office, has earned him even greater respect and authority. His spirit lifts us up to want to play our own modest part in the promotion of equality and human dignity in every little corner of the earth in which we find ourselves. To the extent that we would factor but a bit of that Madiba-spirit into the life of the faith-community called Church, and from there into the world, we would see an infinitely better, freer, and more peaceful human community.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, March 2014. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.