Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death – even death on a cross. [Philippians 2:5-8, NRSV]

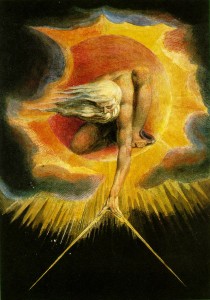

[L] A common artistic depiction of God as the old man in the sky. [M] Ancient of Days (God as an Architect) by William Blake. [R] Crucifixion by Theophanes the Cretan, 16C..

A first image of God

When asked whether their first go-to image of God is “an old man in the sky with a long beard”, adult Christians often replied affirmatively, if a little embarrassed.

This is understandable, since the prayer which Jesus taught his disciples to pray began with “Our Father, who art in heaven…” The elderly father walking on the clouds has got to be a pretty old gentleman with a pretty long and gray beard.

The problem is, we may have stayed [if subconsciously] with that anthropomorphic image, which we first picked up in our early years, well into mature adulthood.

We recall how two professed religious brothers from Thailand, who were our first-year theology classmates, were surprised to learn that when we prayed, the image in our heads were not the old-man-in-the-sky, but the mountains and the seas amongst which the Spirit roamed freely. In moments of “mindfulness”, the recollection of God as Pure Spirit, as the Wholly Transcendent Other, thoroughly unbound or unlimited to the shape and form of a human person, causes us embarrassment. That is when we realize that our image of the Theos as the grand old man can be pretty “juvenile” and problematic.

Even that, in fact, may be the least of our “problems” in our understanding of God. Our incomprehension may actually be far deeper than we are conscious or “mindful” of. People in reality worship the “god” of their choice, but that may not necessarily be the God as revealed in Jesus. In particular, the powerlessness of God has always been a problem for those who start their theology from the perspective of an Almighty God.

Take, for instance, the Creed, in which we pray “I believe in God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth…” God as an almighty deity is a concept not exclusive to the Christians. Any supreme deity in any religion at all has got to be “almighty” and “all-powerful” to its adherents.

On the one hand, this seems so “absolutely” necessary and a “divine” truth. For if we do not accept some kind of an all-powerful interventionist God, how do we comprehend the depth and breadth and the practicality of what prayer is in public and private, conversation and meditation, communal liturgy and contemplation? After all, the God of the Bible is so inherently a God of miracles, that a Christian has got to be a genuine believer in a God that causes miracles, a Lord that saves us from “impossible” and “hopeless” situations. Furthermore, a Christian believes that our God is still in the business of miracle-making and will continue to be so. As for why miracles are made here and not there, or for this person and not that person and so on, it is something to which we have no answer, but that in no way diminishes the fact that God works miracles as and when He wishes. To believe in the Judeo-Christian God, is to believe in the One who is referred to as “The Most High,” “The Heavenly Father,” “The God of the Universe,” and “The Creator of all things seen and unseen.” In our every traditional description of God, therefore, there is no hint other than to a powerful and almighty divinity.

The powerlessness of God

And yet, the mystery of God, as we know, is often a paradox.

And so, on the other hand, even as Christians speak of a God of power, they also have a real sense that God has somehow intended power to shine forth not just in sheer miracles, but even more deeply and in a more enduring way, in the kenotic life and example of Jesus the Christ and of his disciples, especially those who live a saintly and sacrificial life, emptying themselves of all powers and pretensions to power, in imitation of their Lord. This deeper sense of the truth of God, however, is seldom consciously articulated. Regrettably, therefore, our image of God is commonly askew. Lacking in that image of power is the essential, complementary understanding of the real powerlessness of God.

In consciousness, we realize that to preach a God who is almighty is at once problematic when six million Jews, his chosen people, died in the hands of the Nazis. And so, Elie Wiesel, a Jew who survived the Auschwitz Nazi concentration camp and went on to become a Nobel Laureate later in life, wrote the terrifying account in Night. Struggling with the idea of an almighty God who “let” this holocaust happen, Wiesel concluded that God is “hanging here from this gallows.” And so Jürgen Moltmann in his Christological study, The Crucified God, is persuaded to speak of a God who experiences “godforsakenness”. Dorothy Sölle, too, in her Christological study, Christ the Representative, declares an end to the traditional “vertical” idea of God as the all-powerful lord of history controlling the world from above and, instead, depicts Christ as one who, in God’s place and as God’s representative, suffers and dies with us.

St Paul was no stranger to the immense difficulties in preaching the Crucified Christ as “Good News” while the people associated God with almighty powers. The cross of Christ was “a stumbling block to Jews” [1 Cor 1:23] who questioned God’s morality.

- How could a holy God have anything to do with a crucified criminal? “Anyone hanged on a tree was cursed by God.” So Jesus deserved what he got, for if he was innocent, God would not let him die this way. Surely, a criminal, hanging naked and bloody on a Roman cross, was no Jewish Saviour of the world. So the morality of God would always be a problem for those who start their theology from this perspective, and so it was for the ancient Jews.

Likewise, the cross of Christ was “foolishness to the Greeks”.

- The god of the philosophers could not die. The Greeks simply could not intellectually accept a god who could suffer and die.

So Paul had to clarify the link between the “power and wisdom of God” and the seeming powerlessness of Christ on the cross. His problems were huge, for the ancients feared the gods for their awesome power. If something good occurred, it was a blessing from the gods; when something bad happened, the gods must be angry. Sacrifice was the means by which the will of the Judeo-God was discerned or by which the pagan gods were appeased and blessing sought. The Latin phrase ‘deus ex machina’ [god out of a machine] aptly describes “a god lowered from a basket to rescue the day” on a stage play. So Paul, the apostle of the Crucified Lord, was mindful of how problematic it was to preach an almighty God when His Son had to die a horrendous death on the cross. But Paul faced the cross squarely. Insisting that the Crucified Christ is indeed the “power and wisdom of God”, Paul wrote to the Corinthians:

- 17 For Christ did not send me to baptize but to proclaim the gospel, and not with eloquent wisdom, so that the cross of Christ might not be emptied of its power. 18 For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. 19 For it is written, “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning I will thwart.” 20 Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? 21 For since, in the wisdom of God, the world did not know God through wisdom, God decided, through the foolishness of our proclamation, to save those who believe. 22 For Jews demand signs and Greeks desire wisdom, 23 but we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, 24 but to those who are the called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. 25 For God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom, and God’s weakness is stronger than human strength. [1 Cor 1:17-25, NRSV]

Only the Suffering God can help

Repeatedly in the New Testament, we find God not among the wealthy, the mighty, and the powerful, but among the hungry, the poor, the blind and the lame. In the great Sermon on the Mount [Matthews 5-7], Jesus gives a perspective not from the centre of power, but from the margins, taking the side of the poor and suffering, the persecuted and victimized.

- And yet, when we give a theological explanation of the death of Jesus, we ignore the fact of his crucifixion as a social scapegoat, a victim of the ideologies of the religious and political powers of the day, and turn it into that of a sacrifice. Instead of a revelation of anti-sacrifice that it was, we propose it as a sacrifice and thereby mute the deeper power, wisdom and logic of God’s revelation. We have taken on the interpretation of the persecutors rather than that of the victim.

In his letter of July 16, 1944 from his cell at the Nazi prison in Tegel, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote to his friend Eberhard Bethge, addressing the problem of Christian belief in a powerful God:

- “God would have us know that we must live as humans who manage our lives without him. The God who is with us is the God who forsakes us (Mk. 15:34). The God who lets us live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God and with God we live without God. God lets himself be pushed out of the world and onto the cross. He is weak and powerless in the world, and that is precisely the way, the only way, in which he is with us and helps us. Matt. 8:17 makes it quite clear that Christ helps us, not by virtue of his omnipotence, but by virtue of his weakness and suffering.

- Here is the decisive difference between Christianity and all religions. Human religiosity makes one look in one’s distress to the power of God in the world: God is the deus ex machina. The Bible directs us to God’s powerlessness and suffering; only the suffering God can help.” (Letters and Papers from Prison, 360-361).

Bonhoeffer has thereby placed his finger on a major problem of Christian theology and faith.

- Is it not the case that we are too embarrassed and uncomfortable with the “offense of the cross” to face the fact of the Saviour being utterly humiliated and tortured to death, that we would prefer a God who is all powerful, who comes to ‘fix’ things?

- However we might explain God’s involvement in the crucifixion or his post-crucifixion-response, have we not quietly accepted the idea that God has somehow sanctioned or acquiesced in humanity’s relentless determination to victimize and scapegoat Jesus?

- Have we not then opted to turn a blind eye to the revelation that actually occurs in the cross which St Paul says is “scandal to the Jews and foolishness to the Greeks”?

- Is this not common amongst all manner of Christianities?

Accepting a crude ‘theology of glory’, or a gross “gospel of wealth”, people buy into a god who can do anything and who micro manages the world, and they live with the illusion of a deus ex machina and not the Living God revealed in powerlessness. There is a persistent clean jump to the resurrection, viewing the cross as past-tense – Christ’s work is finished, he is now victorious and in glory, so Christians are meant to live in a new reality of utter glory and plenitude. But the New Testament does not in any way portray Christian lives to be in that fashion. Jesus’ resurrection is not to be conceived in categories of sheer power. Rather, until we have comprehended God’s powerlessness, until we have learned to see through the eyes of the Crucified, until we have experienced ourselves as self-deceived persecutors, we would all sooner turn the resurrection of Jesus into a deus ex machina event. That explains why, wherever we find Christians exclusively bent on one side of the equation, relishing in the preaching of such pollutants as power, wealth, fame, fortune and miracles and precious little else, they become the hardest people on earth to proclaim the Gospel to.

To keep the other side of the equation in clear view, we need to constantly remind ourselves of Auschwitz and Rwanda, the starving children, the glaring unemployment, the victims of war, abuse, rape and domestic violence. Then, we may see the reality of the God of powerlessness hanging on the cross who seriously needs our help. “Couldn’t you watch and pray with me for an hour?” [Mark 14:37-38; Matthew 26:40-41].

As always, Jesus’ life reflects the nature and being of God. To touch base with that life, we have to get rid of the words of power and the idea of a God in control, images taken from monarchy and patriarchy and despotism. In depth, the Bible testifies to a God who suffers in love, for in God’s wisdom, it is only through love that God is able to bring change and healing into the world. To practice love to the end, the way of God and Christ is to empty oneself of power, even till Calvary [John 3:16; Philippians 2:6-11].

On February 14, 2015, at a Mass at St Peter’s Basilica to install newly appointed cardinals, Pope Francis said the credibility of the church and the Christian message, rests entirely on how Christians serve those marginalized by society. Speaking at length on the need to be compassionate, he urged the 160 or so cardinals present at the ceremony “to serve the Church in such a way that Christians – edified by our witness – will not be tempted to turn to Jesus without turning to the outcast,” for that would only be to become “a closed caste” of men of power within the church but “with nothing authentically ecclesial about it.” Catholic prelates are inauthentic, according to the Holy Father, who do not get out of the mindset and structure of power, “to serve Jesus crucified in every person who is marginalized.” “Truly, the Gospel of the marginalized is where our credibility is at stake, is found and is revealed!”

A blessed Easter to you all!

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, April 2015. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.