“Those who oppress the poor insult their Maker,

but those who are kind to the needy honor him.” [Proverbs 14:31, NRSV]

[1] Pope Francis and the Preferential Option for the Poor

Upon his election to the papacy, Pope Francis has candidly disclosed, the Brazilian Cardinal Claudio Hummes leaned over and whispered in his ear, “Don’t forget the Poor.” In choosing the name Francis for his papacy, the Holy Father responded definitively that he has indeed not forgotten the Poor. Quite the contrary, since the outset of his pontificate, he has set a seal on it, declaring to the world by his name-choice a set of agenda inspired by Christianity’s most glorious saint from Assisi: the Poor, the environment and peace. First on the list is the Poor. It will be a pontificate of the Poor and for the Poor.

What he has been clearly and explicitly trying to do since is to put attention to the poor and needy at the core of who we are as Church and who we are as Christians. The universal Church he was elected to lead, he insists, shall be a Church of the Poor and for the Poor. In so insisting, he is taking his marching order straight from the Kingdom-life and message of the Jesus of the Gospels, to whom he has for long been convinced we need to be pastorally-converted, if we are to put this world – both its natural environment and its social environment – aright again.

In Laudato Si’, therefore, we can expect to see conspicuously embedded a “consistent ethic of life” for the Poor, or as Archbishop Blaise Cupich of Chicago now renders it, a “consistent ethic of solidarity” with the Poor. This consistent ethic is grounded in the conviction that all human life is sacred and all human persons have fundamental dignity, a conviction rooted in the belief that human beings are created in the image of God. In other words, we can expect nothing short of a subtext on the Poor in this encyclical, even as he writes with urgency on the pressing ecological crisis confronting us all.

He speaks of how the cry of the earth and the cry of the Poor are one, pointing out the interconnection of all forms of poverty – environmental and human – and the need to address them in an integral way.

- “The human environment and the natural environment deteriorate together; we cannot adequately combat environmental degradation unless we attend to causes related to human and social degradation. In fact, the deterioration of the environment and of society affects the most vulnerable people on the planet” [LS, 48].

[2] How Are the Poor Affected in the Ecological Crisis?

With experience as pastor to the Latin American Poor, the Holy Father is acutely aware of the unromantic harsh realities confronting the Poor of the earth.

He identifies the many ways in which they suffer from environmental degradation and climate change: atmospheric and water pollution from the waste of mines, farms, factories and throwaway consumer products [LS, 20-22] and intensive use of fossil fuels [LS, 23]. Whether it is depleted fishing grounds, polluted drinking water or homes leveled by storms in rising seas, the Poor suffer the worst consequences of ecological decline, including threats to their means of subsistence and forced migration [LS, 25]. The issue of fresh drinking water threatens poverty-stricken areas and is particularly acute in Africa [LS, 28]. The loss of biodiversity and deforestation threaten not just individual species, but entire ecosystems and the human communities that depend on them [LS, 32-41].

Analysis of environmental degradation in the encyclical zeroes in on the decline in the quality of life and the breakdown of society, especially in urban life. It laments the impoverishment of the quality of life for hundreds of millions by “environmental deterioration, current models of development and the throwaway culture” [LS, 43]. Cities are becoming increasingly less hospitable to human life [LS, 44].

Clearly, the deterioration of human ecology and human habitat are as much the pope’s concerns as the loss of the natural environment. And this has to do with the Catholic Church’s social teaching where the dignity of the human person, especially the Poor, commands special attention.

[3] To What May We Attribute the Plight of the Poor?

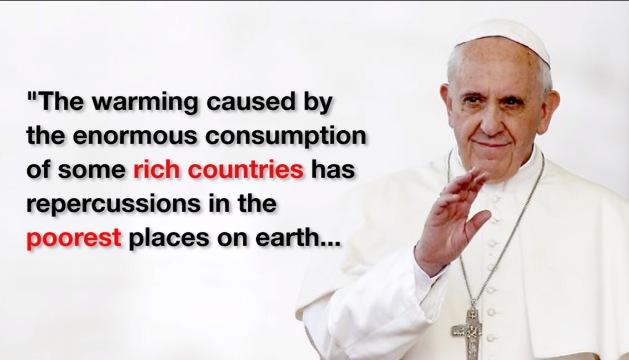

Planet warming, Laudato Si’ declares, is symptom of a greater problem, including:

- The developed world’s indifference to the destruction of the planet as the global north pursues short-term political and economic gains.

- The rich’s indifference to the plight of the Poor in profit-seeking.

- The individuals’ indifference to environmental degradation, both ecological and social.

- The resultant “throwaway culture”: unwanted items and unwanted people [the unborn, the elderly, the poor] are discarded as waste.

It is a bald fact that people in poverty have contributed least to climate change, and that the burden on the planet represented by large poor families is incomparably less than the burden of the lifestyles of small rich families in “developed” economies. And yet, the Poor are disproportionately impacted by environmental decline. Through excessive use of natural resources by wealthy nations, those who are poor experience pollution, lack of access to clean water, and hunger. Land and people suffer injury from the same structural evils: unbridled capitalism, uncontrolled technology and short-sighted politics.

In the light of this, the encyclical raises the two powerful questions described in terms of “ecological debt” and “social debt”.

Paragraph 30, for example, speaks of the water crisis for the poor. It insists:

- “access to safe drinkable water is a basic and universal human right, since it is essential to human survival and, as such, is a condition for the exercise of other human rights. Our world has a grave social debt towards the poor who lack access to drinking water, because they are denied the right to a life consistent with their inalienable dignity.”

Paragraphs 51 and 52 pose a blunt challenge to rich nations, multinational companies, and big businesses to search their conscience on what the Pope calls their “ecological debt”. Technological and economic development must serve human beings and enhance human dignity, instead of creating an economy of exclusion, so that all people have access to what is needed for authentic human development. Protecting nature is incompatible with failure to protect life, especially vulnerable human beings, such as unborn children, people with disabilities, or victims of human trafficking.

So Pope Francis drags us back to where Catholic social teaching began in the industrial revolution and colonialism and the relationship between the developed nations and the developing nations. Because of their excessive consumption pattern, does the developed world not owe an ecological debt to vulnerable populations that are suffering the brunt of ecological damage and climate change?

Actions that came under judgment include the following:

- Development aid has been used to control developing nations, to set their agenda for them.

- Precious resources are taken from the developing world to basically satisfy “super-development” fired by the level of consumption in affluent societies.

- Unscrupulous extractive practices leave behind mercury pollution in gold-mining and sulphur dioxide pollution in copper mining.

- Gas residue deposits now affect all countries.

- Export of solid waste and toxic liquids to developing countries.

- Multinational companies leave behind great human and environmental liabilities including depletion of natural resources, deforestation, open pits and polluted rivers, and plenty more.

The “system of commercial relations and ownership”, the Pope says, “is structurally perverse” [No.52]. Bargaining powers are grossly unequal and unjust; there is no level field. The debate is always dominated by more powerful interests. Greater attention must be to the needs of the Poor. At this particular time, the migrant-crisis has boiled over in Europe. In his September visit to America, Pope Francis mentioned the fact that he is son of migrant parents.

The ferocious pace of economic and technological development has also caused severe inequality. Not only has economic growth of the past two centuries not always led to an integral development and an improvement in the quality of life, especially for the Poor, there are also signs that are “symptomatic of real social decline, the silent rupture of the bonds of integration and social cohesion” [LS, 46].

The Poor and the excluded are particularly hurt by the social segregation of classes in contemporary society. They have all but been reduced to “an afterthought”, referred to in “tangential way”, kept in the “bottom of the pile”, and treated as mere “collateral damage” in international political and economic discussions.

- “This is due partly to the fact that many professionals, opinion makers, communications media and centres of power, being located in affluent urban areas, are far removed from the poor, with little direct contact with their problems. They live and reason from the comfortable position of a high level of development and a quality of life well beyond the reach of the majority of the world’s population. This lack of physical contact and encounter, encouraged at times by the disintegration of our cities, can lead to a numbing of conscience and to tendentious analyses which neglect parts of reality” [LS, 49].

[4] A call for examination of conscience

The document as a whole is an invitation to an examination of conscience. The Pope is a Jesuit, and this invitation is very Ignatian in that instead of a condemnation in the document, what we hear is a tone that invites us to meditation in a very clear, readable and spiritual way. And yet, to be sure, there is judgment, and a pretty strong one at that. At times, it is even very blunt. But, it is really that Ignatian method that makes it a very strong invitation into a profound examination of conscience, as individuals, as community, as a nation, as a multi-national company, as a church, as a world [see LS, 51-52].

In our conscience-examination, we might ask ourselves what we have been doing in our pursuit of happiness, a very human pursuit to be sure. Called to serious question are:

- [1] the pursuit of individual happiness, made into an ideal in our time, to the point of ignoring and disregarding the basic truth that the happiness of the individual depends on its relationship with the rest of human beings;

- [2] the pursuit of financial gain, without taking the context into account, let alone the effects on human dignity and the natural environment.

The pontiff always condemns the impoverishment of developing countries by the world economic order. In Bolivia recently, he said: “Let us not be afraid to say it: we want change, real change, structural change,” decrying a system that “has imposed the mentality of profit at any price, with no concern for social exclusion or the destruction of nature.” Quoting Basil of Caesarea, a fourth century bishop-saint, he called the unfettered pursuit of money “the dung of the devil”, and said poor countries should not be reduced to being providers of raw material and cheap labour for developed countries.

Insisting that a true ecological approach always becomes a social approach, he wants to see the integration of questions of justice in debates on the environment, so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor [LS, 49]. Clearly, he is challenging business men and women, politicians and economists to face some hard questions:

- Are they yielding to an economic model which is idolatrous?

- In their business model, are human dignity and long-term human welfare sacrificed on the altar of money and profit?

- Are they conscious of the environmental evils and social injustices precipitating from their business style?

- Are the interests of the Poor and excluded positively factored into their policies and execution?

- Is essential human dignity denied, or is it promoted and ensured within the vocations of business leaders and politicians?

[5] The use of the Cain and Abel story

The Pope’s aim is transparently to arouse a sense of deep communion with the rest of nature. But this sense of deep communion, he insists, cannot be had, if we do not develop a deep sense of love for the Poor. He goes on to say that this sense of deep communion with the rest of nature “cannot be real if our hearts lack tenderness, compassion and concern for our fellow human beings.” Upon the fundamental conviction that everything in creation is connected, he writes: “Concern for the environment thus needs to be joined to a sincere love for our fellow human beings and an unwavering commitment to resolving the problems of society” [LS, 91].

The story of Cain and Abel is at the forefront of the Pope’s consciousness. Not only does he mention this in paragraph 70, he emphatically stressed it in his visits to Ecuado and elsewhere. And he always challenges his audience with the question: Will our answer continue to be: “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

Some questions we imagine this down-to-earth Holy Father would lay before each one of us are:

- [1] Do I profit on the suffering of others?

- [2] Do I resist the throwaway culture?

- [3] Do I practice inter-generational and intra-generational solidarity?

- [4] Am I suffering from spiritual indifference and am actually spiritually lukewarm?

- [5] What kind of social and ecological environment am I leaving for the next generation?

- [6] Do I resist the technocratic paradigm and help the young to do the same? [e.g. get a few families, or a group of children to spend a weekend in a park, free from electronic gadgets?]

- [7] Do I teach the young properly in terms of these things? Do I teach them to receive a gift with a proper attitude of gratitude, to learn to say “Thank you”?

- [8] Do I remember God the Creator and his gifts to me?

- [9] Is my heart open to the care of the natural environment?

- [10] Is my heart open to the care of the Poor?

Reflected in questions such as these, is Pope Francis’ theological vision of a cosmic family of creatures of the one God. It is a profoundly spiritual vision as well.

- “All of us are linked by unseen bonds and together form a kind of universal family, a sublime communion which fills us with a sacred, affectionate and humble respect”[LS, 89].

It is in this lived vision, as in Saint Francis’ fraternity of God’s creatures (Brother Sun, Sister Moon), that we can overcome the alienation from one another, especially the alienation of the advantaged from the disadvantaged, the rich from the Poor, and the estrangement of humanity from our common earthly home.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, October 2015. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.