“Let us therefore approach the throne of grace with boldness, so that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need” [Hebrews 4:16, NRSV].

The official logo of the Jubilee Year of Mercy.

In April this year, Pope Francis issued a papal bull of indiction, “Misericordia Vultus” (Latin: “The Face of Mercy”), to inaugurate a Special Jubilee Year of Mercy, to run from 8 December 2015, Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary, to the Solemnity of the Feast of Christ the King on 20 November 2016.

The Motto

The motto is “Merciful Like the Father” which echoes verse 6:36 of the Gospel of Luke: “Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful”.

At the official press conference for the unveiling of the logo, it was suggested that with this motto as guiding theme of this Jubilee Year, the Holy Father is issuing an invitation to all Catholics to follow the merciful example of the Father who asks us not to judge or condemn but to forgive and to give love and forgiveness without measure.

Two of Yahweh’s attributes repeatedly stressed in the Old Testament are mercy and fidelity – His graciousness and truth. The ways of Yahweh, the Psalmist proclaims, are mercy and fidelity to them that seek to keep His covenant and decrees [Ps. 25:10]. So we praise the Lord, for He is good, and His mercy endures forever [Ps. 136]. The Old Testament, in this regard, helps Christians gain a better appreciation of the depth and magnitude of the gratia, gift-wrapped and packaged through the Incarnation of the Son of God now popularly known as Christmas. We can read afresh, with energised gratitude, St John’s terse and solemn declaration of the coming of Jesus the Christ in the Prologue of his Gospel: “From his fullness we have all received, grace upon grace. The law indeed was given through Moses; grace and truth [mercy and fidelity] came through Jesus Christ” [John 1:16-17].

Whatever the prophets of old sung about God’s mercy and fidelity, now we see it in concrete reality in the New Testament. While Yahweh of old dwelt with His people in the Tabernacle as they journeyed in the desert, or in the Holy of Holies on Mount Zion when they settled down in Jerusalem, now He lived amongst His people in His Son. No longer do we have to speak in parables of God’s presence amongst us, but in actual fact, for God has come down in person and became man: “And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth [mercy and fidelity]” [John 1:14].

Whereas in Matthew 5:48 the exhortation is to be perfect even as the heavenly Father is perfect, here in Luke 6:36, we are called to be “merciful”, suggesting at once that mercy is not only a principal attribute of God, but indeed the noblest of the divine attributes, in which all others reach their completeness. Hence, in the Incarnate Son, we see the “face of the merciful Father”. “Merciful” and “compassionate” predominate the Son’s characterisation of the heavenly Father [e.g., the Parable of the Prodigal Son in Luke 15], typify his dealings with all who sin [e.g., the woman caught in adultery in John 8], and determine the welcoming and sacrificial spirit we who commune at the Table of the Lord are obligated to live by [e.g., “Do this in memory of me” at the Last Supper, in spite of betrayal and denial foretold in Mark 14:12-31; Matthew 26:17-35; Luke 22:7-38]. This has prompted Pope Francis’ adamant insistence on many occasions that the Eucharist is “not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak” [e.g., Evangelii Gaudium, 47]. Radical and startling, Pope Francis’ message preaches the Gospel of Christ.

Christian morality, Pope Francis has always believed since before he became the Roman Pontiff, is not a herculean effort of the will, but a response to the love and mercy of God. It is part of our human condition to fall, but it is to the glory of God that we are able to get up again after every fall. Preaching on the Gospel reading of Jesus’ forgiveness of the adulterous woman [John 8] at his first public appearance after he was elected pope, Francis emphasized the principle that God never wearies of forgiving sinners and he stressed the importance of we never tiring in asking for forgiveness. Media reports have captured a phenomenon called the “Francis effect” where many have returned to God and to confession on account of this emphasis on God’s mercy.

Mercy and forgiveness are enduring themes in the works of William Shakespeare as well. Perhaps his best known quote on mercy is the passage in Act 4 scene 1 of The Merchant of Venice, on the “quality of mercy”. Holding those who showed mercy in high esteem, the famous playwright presented mercy as a quality most valuable to the most powerful, strongest and highest people in society. It reads:

The quality of mercy is not strain’d,

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath: it is twice blest;

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes:

‘Tis mightiest in the mightiest: it becomes

The throned monarch better than his crown;

His sceptre shows the force of temporal power,

The attribute to awe and majesty,

Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings;

But mercy is above this sceptred sway;

It is enthroned in the hearts of kings,

It is an attribute to God himself;

And earthly power doth then show likest God’s

When mercy seasons justice. Therefore, Jew,

Though justice be thy plea, consider this,

That, in the course of justice, none of us

Should see salvation: we do pray for mercy;

And that same prayer doth teach us all to render

The deeds of mercy. I have spoke thus much

To mitigate the justice of thy plea;

Which if thou follow, this strict court of Venice

Must needs give sentence ‘gainst the merchant there.

The Official Logo

On first sight, the logo depicts a man carrying another man across his shoulders. But other details quickly point us to him as the Christ, for he has the familiar halo of the Pantocrator [meaning “Almighty” or “All-powerful”] and his hands and feet show the pierced marks. One particular detail is at once striking, and that is Christ’s eyes merge with the man’s so that we see not four eyes, but three.

The official explanation offers interesting elements for further reflection.

1. It portrays the figure of the Good Shepherd carrying the lost soul that provides a fitting summary of what the Jubilee Year is all about.

2. The logo is the work of Father Marko I. Rupnik.

3. It is an image quite important to the early Church: that of the Son having taken upon His shoulders the lost soul, demonstrating that it is Christ’s love that brings to completion the mystery of His incarnation culminating in redemption.

4. The logo has been so designed to express the profound way in which the Good Shepherd touches the flesh of humanity and does so with a love that has the power to change one’s life.

5. While the Good Shepherd, in His great mercy, takes humanity upon Himself, His eyes are merged with those of man. Christ sees with the eyes of Adam, and Adam with the eyes of Christ. Every person discovers in Christ, the new Adam, his or her own humanity and “the way, the truth and the life” to a hopeful future.

6. The scene is enclosed in a mandorla, an element typical of ancient and medieval iconography, that recalls the coexistence of the two natures, divine and human, in Christ.

7. The three concentric ovals, with colours progressively lighter as we move outward, suggest the movement of Christ Who carries humanity out of the darkness of sin and death. Conversely, the depth of the darker colour suggests the impenetrability of the love of the Father Who forgives all.

We would venture to add that, more than a depiction of the Good Shepherd whom Christ alone is, the image here is a juxtaposition of both the Good Shepherd and the Good Samaritan. In Eastern spirituality, explained by St Augustine, Christ is the Good Samaritan who just would not leave the injured humanity unattended to. With no question asked, and without counting the costs to himself, Christ the Good Samaritan would carry the injured man to an inn to be safely cared for, even though at his own birth, St Luke made it clear that cold-hearted humanity had “no room” for him and his family at the inn. The mercy of God knows no bounds.

A Word on the Mandorla

In the art of iconography, the use of mandorla and light is key. Icons are windows to heaven, theology in colour. Take, for example, the beautiful 16th century mosaic icon of the Transfiguration housed in St Catherine’s Monastery on Sinai. The mandorla, representing Christ’s glory, is an iconographic depiction of light. This is most obvious in all icons of the Transfiguration, where the mandorla is used to image the countenance of Christ before His disciples on Mount Tabor, which was “white and glistening”.

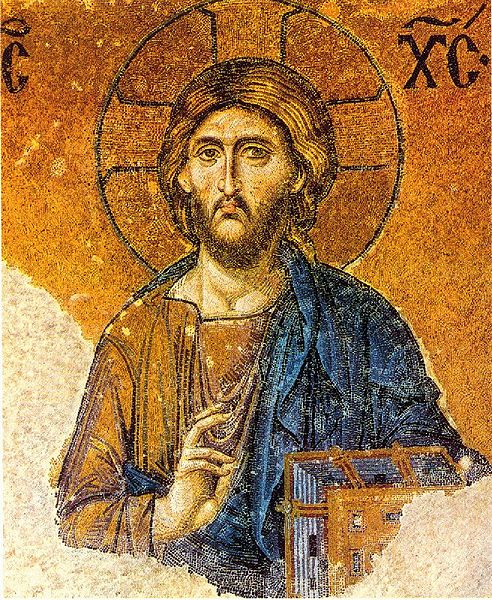

[L] One of the most famous art work of Pantocrator is the Orthodox icon of Jesus Christ Pantocrator (Detail from deesis mosaic) from Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

[R] The mosaic of Transfiguration at St Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai.

At the same time, what the mandorla is showing is not something which was seen directly, but represents the glory and majesty beyond what was physically witnessed by the gathered crowds. So, for instance, at the Transfiguration, the voice of God spoke from beyond the cloud [Matthew 17:1-13; Luke 9:28-36], clearly paralleling the cloud Moses entered in order to converse with God. This is present in the Mercy-logo today, represented by the three-tiered mandorla. At the heart of God’s revelation to the Jews, and later we Christians, is the paradoxical impossibility to comprehend God. Revelation, in reality, is veiling at the same time. We ought never be so arrogant as to suggest that we know all about God. But to know God, to encounter and converse with Him, and to experience God’s powerful presence is possible. It happens through bending one’s knees, and entering this “cloud of unknowing”.

In this regard, the mandorla in the mercy-logo has two features deserving of our attention. First, it is oval-shaped, indicating the intersecting of two circles that come together, encapsulating the infinite and the finite, the two natures of divinity and humanity. Second, it has three concentric bands of shading which get darker towards the centre, rather than lighter. This suggests different steps of manifestation of the divine leading to a dark center which is impassable to mere humans. What Scripture cannot express in words, icons seek to capture in the mandorla. And yet, what we can experience of God’s glory goes beyond even images. We must pass through stages of what seem like increasing mystery and unknowing, in order to encounter Jesus Christ. Then, we can appreciate the three-tiered mandorla as an invitation to enter into humble communion with Christ, to sit at his feet like Mary of Bethany, to learn about mercy from the Master Himself.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, December 2015. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.