39 And no one after drinking old wine desires new wine, but says, ‘The old is good.’ [Luke 5:39, NRSV]

Luke’s Gospel in chapter five suggests that “old wine” is valued so much more over “new wine”.

Wine aging is commonly practised upon the expectation that as wine ages, it potentially improves its quality. That result, of course, is neither automatic nor guaranteed. Wine, after all, is perishable and is well capable of deteriorating like all consumable goods. The truth of the matter is, fruits degrade over time. The ability of a wine to age well then, depends on many factors, including the grape variety, the winemaking technique, the condition of the bottle and the cork, and the condition in which the wine is stored after bottling, and so on. Only from the 16th and 17th centuries onwards, as sweeter and more alcoholic wines were produced, coupled with corking and bottling, the adding of alcohol as preservative and improved storage, did the industry considerably overcome the simple reality of wine turning into vinegar after just a few months. In a word, conscious effort is needed to preserve and even improve wine quality over time.

The point for our reflection is: if that is true of wine, it is certainly true of human dignity.

We are reminded of the conversation between Jiang Weiqing (江渭清) and Zhu De (朱德) during the decade-long (1966-1976) “cultural revolution” in China, formally known as the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution”. A sociopolitical movement, it was a “Revolution” within the Chinese communist revolution set into motion by the then Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong. The blame was laid squarely at the doors of all wildly alleged “remnants” of capitalist and traditional elements who must be purged from the Chinese society. While the official goal of this Revolution was to preserve ‘true’ Communist ideology in the country, the real goal was to impose Maoist thought as the dominant ideology within the Party, regardless of pervasive signs of his failed economic policies that were causing perishing hunger and wrenching hardship across the recently liberated nation. As the Revolution marked the consolidation of Mao’s position of unshakable supreme command, it also paralyzed China politically and adversely degraded the spirit of the people as well as the country’s economy. The nation as a whole was extremely poor and, across the immense territory, her common people lived in abject poverty. Denied university education, urban youth were “sent down” to rural regions to learn rural living. Resonant with its fierce disdain for all things intellectual, the movement destroyed historical relics and artifacts, and ransacked cultural and religious sites. It was a time of sheer madness. People lived in fear. Not until after the death of Mao and the arrest of the infamous “Gang of Four” in 1976, was the widespread factional struggles in all walks of life finally put to a stop. Reformers led by Deng Xiaoping gradually began to dismantle the Maoist policies associated with the Cultural Revolution. In 1981, the Party declared that the Cultural Revolution was “responsible for the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the Party, the country, and the people since the founding of the People’s Republic“.

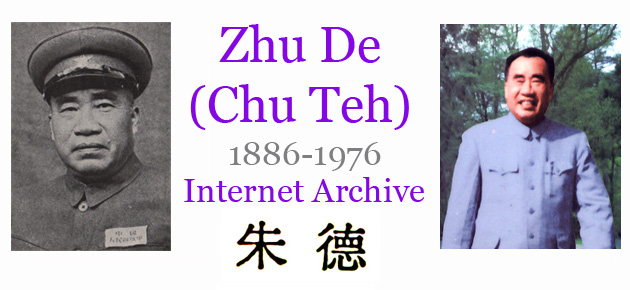

While the Revolution was raging, senior officials, most notably Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, were purged and packed off to isolated regions for hard labour, while Mao’s personality cult peaked at dizzy height. Caught in all that, was one Jiang Weiqing (1910 – 2000). He was the Communist Party Committee Secretary and CPPCC Committee Chairman of Jiangsu Province and Communist Party of China Committee Secretary of Jiangxi Province. Loosely branded a “capitalist”, Jiang was summoned to Beijing for questioning and “cleansing”. At this lowest point of his life, Jiang was shunned by all who feared “contamination” by association. In precisely such hard circumstances, Zhu De, the retired Commander General of the army, saw the need to preserve human dignity. He reached out to Jiang and invited him to his home for dinner.

Zhu was the man who first founded the Red Army and was deeply revered across the country for the “Zhu-Mao” recognition at the early inception of the Communist revolution. After the Communist Party has driven out Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuo Ming Tang and assumed the governance of the country, Zhu took charge of the development of the missile launching weaponry and then the nuclear bomb capabilities of China. But now, in old age, even he was loosely branded “a capitalist” and sporadically targeted for image-degradation and character-assassination in this mad Revolution. Just as crisis times reveal people’s true characters, the incredible dignity of Zhu shone through precisely at this time. Zhu, a man known not only for his military brilliance, but even more so for his moral uprightness and fortitude, brushed aside the obvious personal dangers and openly had Jiang invited to dinner in his home.

In Beijing, one must know, nobody dared to even meet Jiang, let alone be hospitable to him, for fear of reprisal from those in power who were bent on purging all senior officials whom they had bookmarked for branding as “capitalist-leaning”. So Jiang would not even be able to find a place to eat, Zhu told his wife. Zhu sent his secretary to fetch Jiang by car. For fear of causing trouble to Zhu, Jiang at first declined the offer, saying, “When one reaches a point like this, his heart is chilled right through.” But Jiang relented upon the secretary conveying Zhu’s insistence.

At dinner, Zhu brought out the best jar of wine. This was wine brought back by his children from his home village in Sichuan which he had kept for a few decades now. Calling that aged wine a “national treasure”, Jiang begged Zhu to please save it for a more appropriate occasion. Zhu, however, declared that Jiang was the right person for him to drink it with. What Zhu said to Jiang were words good for the soul.

Listen to those powerful words (our translation):

-

“Weiqing, we have been doing revolution for a few decades now. What wind and storm have we not experienced? So what’s this current puny little wind and storm to us? We must be like a jar of wine, a jar of good wine. A jar of water stored for a few decades would have long gone bad, how can we drink it? But a jar of good wine grows stronger and tastes better the longer it is aged – always with this strong, deep and enduring fragrance. Weiqing, be strong, no matter how the wind and the storm may change. You are not a jar of water. You are a jar of good wine. And that is enough!”

Right here, Christians turn to their Scriptures which console and affirm:

- “For all who do evil hate the light and do not come to the light, so that their deeds may not be exposed. But those who do what is true come to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that their deeds have been done in God.” [John 3:20-21]

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, February 2017. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.