“This day I call heaven and earth as witnesses against you that I have set before you life and death, blessings and curses. Now choose life, so that you and your children may live” [Deuteronomy 30:19]

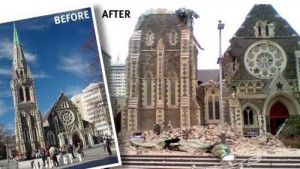

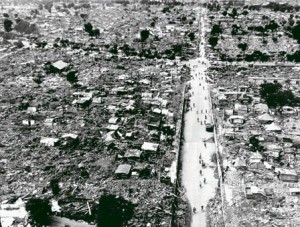

[1] Christchurch Cathedral , a beautiful national treasure, in ruins after the earthquake, with its collapsed spire visible in the foreground 22 February 2011 [2] Tangshan earthquake 1976, ruins and tents.

Life breaks us all. Broken lives. Broken relationships.

Natural disasters compound and exacerbate human suffering.

And yet, because we resonate with pain and suffering wherever we see it, these disasters are always immense opportunities for reflection and growth, both for the individuals and for society as a whole.

Only very recently, world attention was on New Zealand when a terrifying earthquake hit its second largest city on Tuesday 22 February. The country’s deadliest natural disaster in 80 years struck at 12:51 pm, 10 km (6.2 miles) south-east of Christchurch. A camera technician told Reuters news agency the area outside the land mark cathedral was “like a war zone”. City Mayor Bob Parker told the BBC: “This is a terrible, terrible toll on our city… There is no power in most of the city; there is no water in most of the city.” A British backpacker said the city “looked like a bomb had hit it”. Financial losses could be estimated at a few billion dollars, but there is no way to tag the cost of human lives, trauma and suffering. Like all other natural disasters, we see a community in agony. Never was the need for community stronger, and never was the sense of community more palpable as people came together, to check and support one another. It warmed hearts to see the international community acting in solidarity with the New Zealanders and arriving with rescue teams at the first opportunity. Disasters may force individuals to their knees; and yet, humanity triumphs through a soul that refuses to be crushed, and is generous in outreach to others, thereby giving glory to its Divine Origin.

On March 11, as the New Zealanders were still reeling in the endless aftershocks of the Christchurch quake, the Japanese were dealt with the worst disaster in their country’s history after World War II, when a monster quake, now revised to 9.0 magnitude, hit just off the north-eastern coast of Japan. The international scientific community reported that the monster quake had shifted the earth’s rotation axis by about 25 centimetres. The thrusting of the Pacific and North American tectonic plates that caused the quake had spawned a massive killer tsunami that hit Japan before racing across the Pacific Ocean to Hawaii and the West Coast of the United States. Even as structural damage in Japan is being assessed at a hundred billion dollars and more, it seems clear that the surging death toll as floods recede will be the real unfolding horror.

As if that’s not enough, the catastrophes are mounting as the cooling systems at two nuclear power plants failed, with one unit actually exploding, and the danger of deadly radiation becomes pressingly real not just for the Japanese population, but for the rest of Asia.

In the midst of all this, foreigners living in Japan noticed an aspect of the culture alive in the Japanese society which others can learn from. In the face of this immense tragedy, there is a cultivated calm, civility and orderliness. Thanks to a legacy of wisdom accumulated through past national tragedies, TV stations do not seek to sensationalise the disaster for rating purposes, politicians do not scream over their heads at political foes to raise their public standing, victims who lost houses and family members do not howl and scream and curse the government for gross incompetence the moment the natural disaster hits, and people do not loot, or add to the chaos and create civil unrest. Instead, as devastation sweeps Japan, her citizens queue up silently and civilly at train stations as they do in supermarkets where shelves are fast emptying. They buy only what they need. Politicians from different camps set aside their differences and work in unity. Even the criminal gangs are appreciated for acting expeditiously in opening up shelters and relief centres. People just get on with doing what need to be done for the good of the community. What the 21st century Japanese people have shown the rest of the world is that life can still be civil and dignified and disciplined even in the face of incredible devastation. Natural disasters may darken the face of the earth but, somehow, they also have the tendency to spotlight the beauty embedded in the human soul – a beauty that glorifies its Maker.

Impressed to their core by this particular dimension of the Japanese culture, many Taiwanese do not wish any of this to be lost on their people who have in recent memory consistently shown a different, and decidedly more negative, face of human culture. So one Taiwanese National TV station [TVBS] is dedicating exclusive programmes to discuss the wild differences between Japan and Taiwan in how society behaves in the face of national disasters.

At the same time, however, they do not relent where critical scrutiny is called for, as the international community holds its breath while it is stunned by the incredulous and growing exposure of nuclear leakages which the local management has been trying to cover up since March 11. The decisions and choices they make in the way of cover-up are ultimately self-defeating. Their “culture of shame”, which works marvelously in one direction in a civil society as we have noted, is depressingly negative when it works insidiously in another direction, the way of cover-ups at all costs. They highlight for us the magnitude of structural and spiritual flaws in companies as in organisations, in governments as in churches:

- secrecy

- lack of accountability

- non-tolerance of criticism

- group benefits above all else

- a group discipline of silence that is altogether quite “sick” in what it is willing to inflict upon the rest of the community.

All this brings us back to the horrific disaster in China, when an earthquake measuring 7.8 on the Richter scale hit Tangshan on 28 July 1976. Striking mercilessly in the death of night, the monster quake obliterated the sleeping city, killing around 250,000 people and severely wounding another 160,000.

Wishing neither to sensationalise the scale of the disaster, nor to profit from human suffering, but desiring to cherish the beauty of the human spirit ensnared in an overwhelming crisis, China’s 2010 blockbuster movie, Aftershock [a.k.a. Tangshan Dadizhen, 唐山大地震] is a worthy piece from the entertainment industry.

The first IMAX-quality film to be produced outside of the United States, Aftershock is an irresistibly engaging tear-jerker. With each cinema ticket, theatres across China handed out little tissue packets for the unavoidable tears. Where posters implied it to be a disaster movie, viewers knew they were in for something far more subtle and ambitious. Within minutes after the movie begins, the earthquake has occurred and lives have been scarred forever. What follows is a close-up look at how people deal with such an impossible disaster and continue on with their lives. It is a searing drama about a family ripped apart, both physically and emotionally, by the terrifying, unforgiving, natural disaster.

An important part of the film’s immense attraction lies in its vision, which is to portray a human drama rather than a spectacle of natural disaster. So this is anything but a typical disaster movie. Indeed, an exploitation of the earthquake for big screen thrills would have been in remarkably bad taste. Instead, the audience is treated to a marvelous opening segment of a swamp of dragon flies that hurried off the city, an ominous sign of something unknown of major proportions about to break out. The Hollywood type high-tech visual effect of the quake proper that followed took up a rather brief stretch, which fits in well with the shocking fact that despite causing colossal destruction, the quake itself only lasted 23 seconds. The massive destruction sets up the necessary historical background for this touching family drama.

Far less concerned with collapsing buildings than with people in them and much more invested in piecing things back together than breaking them up, the enduring line in the movie is whether traumatized and deeply hurt family members can somehow dig deep to garner the strength to forgive themselves and each other, so as to find reconciliation and peace. It tells the story of human devastation, of lives lost, of families shattered, and of the emotional aftershocks of the survivors. For that, it resorts to a classic form of melodrama familiar to Chinese cinema and reminiscent of classic Hollywood dramas. A weepie it certainly is but, tastefully, there is no sentimental overkill. It is a movie in which the director respectfully explores the pain of human loss and the even more excruciating pain of human estrangement.

Through a Chinese lens, viewers come face to face with such universal themes as family, sacrifice, loyalty, love and, above all, forgiveness. Whilst it features a specific tale of a family being cruelly torn apart by a mega earthquake, the story touches hearts because it rings powerfully true in universal experience of a troubling estrangement before a painful reconciliation. In the season of Lent, it somehow reminds us of the Christian journey of pain and hope, of suffering and resurrection.

But there is one particular element in the movie that holds special attraction for us. It has to do with heart-wrenching decisions being cruelly foisted on individuals who could not recover from the painful human estrangement that ensued. In contemplation afterwards, what bothered us incessantly is the “deaths” associated with decisions.

A decision is a choice. A choice is a sacrifice.

In making a decision, we choose one thing and “sacrifice” other possibilities.

We are born free, but everywhere we turn, we are in chains. In dreams, all things can be beautiful and we may not have to choose. In the real world, things are hardly ever perfect and making choices is just part of the deal. The human condition is one of endless limitations in the face of endless choices. Opportunities are aplenty, but a choice, once made, is at once acceptance of the one and death to the rest. For good or bad, the die is cast, and one has to live with it. And yet, hard though some excruciating decisions may be, they are the test of maturity, and of the acceptance that the human condition carries no choiceless privileges. Every human life is a story of endless deaths in endless choices.

In Aftershock [or Tangshan Dadizhen], a young mother was faced with the impossible task of choosing which of her two children, pinned under a concrete slab, to save. The rescue workers could not save both. If she refused to decide or delayed any longer to do so, both would die as workers moved on to save others. In choosing to save the boy, instead of the girl, she opened a window into a family culture through a Chinese lens, and “heavens” had “unjustly” foisted on her a decision she never wanted to, and never in her wildest dream imagined she would, make. Life was simply too cruel to a mother caught at the wrong place at the wrong time. Viewers recall Sophie’s Choice, in which Meryl Streep who won an Oscar for best actress faced an excruciating dilemma. While being unloaded in the Auschwitz death camp, a sadistic doctor made her choose which of her two children would die immediately by gassing and which would continue to live, albeit in the camp. Of her two children, Sophie chose to sacrifice her seven-year-old daughter, Eva, in a heart-rending decision that left her in mourning and filled with a guilt that she could not overcome. Surviving Auschwitz, Sophie was tormented by that memory for the rest of her life. Turning alcoholic and deeply depressed, she was ever-ready to self-destruct.

In Tangshan Dadizhen, the girl, given up for dead, unexpectedly survived and, as it were, rose from the ashes. Adopted by a couple in military service, she lived the next 32 years in unremitting resentment in her soul, steadfastly refusing to return to Tangshan to see the mother and brother, and never even letting them know that she in fact was alive. The mother, in the mean time, lived an ascetic life, punishing and tormenting herself with guilt for the 32 years until the family was finally healed through forgiveness and reconciliation. It would take yet another deadly earthquake – measuring 8.0 on 12 May 2008 in Sichuan province of China that killed at least 68,000 people – to bring the brother and sister together as volunteer rescue workers and, as virtual strangers, to begin the tough journey of forgiveness and reconciliation. Go see the movie. It’s good for the soul! There’s plenty of impressive acting too, especially by the director’s wife, who plays the role of the suffering mother who, as the Chinese expression puts it, “daily washes her face with her tears”.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, March 2011. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to us at jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.